“What Does it Mean, to Heal?”

Issue #6, May 2018

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Lise Weil, Kristin Flyntz, Deena Metzger, Laura Bellmay, Erica Charis-Molling, Kim Chernin, Wendy Gorchinsky-Lambo

Editorial

Kim Chernin

Mother of Us: A Prayer for Healing

Cynthia Travis

The Wisdom of the Breakdown

Deena Metzger

Can the World Mend in this Body?

Verena Stefan

Quitting Chemo

Laura D. Bellmay

The Unveiling: Notes on Illness and Beauty

Erica Charis-Molling

Requiem in the Key of Bees, a Cento

The End of Night

The End of Night

Wendy Gorchinsky-Lambo

Making Love with a Three-Billion-Year-Old Woman

AFTERMATH: 11/9

Praying Amid the Damage: Dreams, Nightmares, Visions

Karen Mutter

Jaguar Medicine

Anne Bergeron

The Seven Jars

Laura D. Bellmay

The Unveiling: Notes on Illness & Beauty

Beauty, like love, is a fierce power that restores the world. The healer’s power is diminished if it is not associated with beauty. Healing helps align the individual with the trajectory of the soul.

~ Deena Metzger, 2004, keynote address, "The Soul of Medicine"

“Shouldn’t she be better by now?” my friends quietly asked each other.

It was December of 2001, nine months after my mastectomy for a recurrence of breast cancer. The regimen of intensive chemotherapy left me as close to death as the cancer that had tried to consume me. I felt depleted in body and spirit, my soul water- boarded.

Those close to me said, “Aren’t you glad chemotherapy is over? Why don’t you get out of the house?” What are your plans for the holidays?”

Between the lines, I heard annoyance and a demand that I ‘move on.’ But I had no idea how to leave cancer behind.

Friends stopped calling; their visits were fewer. Flowers no longer came in robust bouquets and cards and calls of encouragement ebbed. My husband’s patience wore thin.

In the upstairs bathroom one evening, I turned off the faucet after washing my face. My husband yelled up from the living room where he was watching television, “Go easy on the pipes!”

I looked into the mirror. An emaciated, bald, crying ghost stared back. My eyes would not look at the crater where my right breast had been in a body I could not seem to love. I’d lost what I thought defined me as a woman and my husband was concerned only with the plumbing.

I had worked so hard to live and now I just wanted to die.

Then, at a gathering of women, an artist friend suggested I pose for an art class at the University of Hartford. She hoped it might give meaning to my ordeal while providing young art students a unique and challenging painting opportunity.

The thought of posing nude horrified me. I remembered summer camp when I was eight years old, changing into my bathing suit in a 100-hundred-degree bug-infested outhouse so the other girls would not see me naked.

Surviving cancer twice meant that I had been poked, prodded, and pricked repeatedly over many years. When I was hospitalized for six days with a fever of 104 degrees after my third intravenous chemotherapy, IV antibiotics could not relieve the bloom of painful and “mysterious” lumps that flourished on my labia. A mob scene erupted in the examining room when five “medical specialists” gathered for the view between my legs.

I no longer felt I was in control of my own body. I was afraid if I posed, I would be objectified as I had been before. But I could not allow fear to win. I wanted—and needed—to take charge of what I could in spite of all I’d lost. Posing felt to me like one thing I could do on behalf of my healing. I no longer cared if what I did made sense to anyone else.

I arrived at a tiny room in the Art Department of The University of Hartford. Easels, unfinished oil paintings, and old rags lay scattered around. I took off my winter boots and coat and met the painting teacher, Stephen Brown. After introductions and small talk, he revealed that he too was a cancer survivor and had lived many years with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. I felt heartened by this connection.

I changed into a fluffy white robe. Professor Brown then brought me to his classroom to meet his students, all eighteen of whom started talking simultaneously.

“We don’t bite. You’ll have fun today, really,” said a woman with a wide smile and dreadlocks. The mood in the classroom was festive and I calmed a bit. Stephen brought me over to the raised platform where he told me I could sit or stand whichever was more comfortable for me.

I laughed, “Really, I’m not comfortable at all. I’m scared.”

Professor Brown stationed four space heaters in front of the platform where I would soon stand. My body gave an involuntary shake anyway.

“If you need a break from posing at any point, just say so,” one of the students said.

“Most models,” Stephen said, “ask for water, or need to move after holding a pose for twenty to thirty minutes. You’re in charge really.”

Yes, I was. I liked that.

Once on the platform in the class I was too frail to stand in front of the canvas backdrop as other models did. I prayed in silence, “May what is created here today benefit all beings.” Then I adjusted my bony rear end into an old wooden rocking chair, placed my long scarf across my lap, and dropped my bathrobe.

Goose bumps formed on my upper body and the chill turned my fingers white. After the initial jitters wore off an intense calm embraced me like a warm cocoon. The buzz of the heaters became a comforting whirr as the students focused on their canvasses. Occasionally, a student looked at me for what felt like a long time, but they did not stare. Nor did they chatter among themselves.

I closed my eyes. I felt holy.

Stephen left the room. I remembered nothing until he returned an hour later and asked, “Are you tired? Do you need a break?” Leaning back in the rocking chair, I arched my chest and stretched my arms overhead as if making a snow angel in the air. “Nope, I’m in the zone, best not to interrupt the flow.”

One young woman released an appreciative sigh. Echoing Stephen, she said, “Most models move around a lot or take breaks after fifteen minutes.”

“Yeah, she’s right,” said another. “You can come back any time.”

The vote of confidence from these young men and women brightened me. For more than ninety-minutes, I rested in a living prayer. The only sounds I heard were the space heaters at my feet and the soft scratching of paintbrushes across canvas.

For most of my life, and for years as a survivor of sexual abuse, I had been treated as an object. As the subject of the student artists, however, I did not feel objectified. Their respect, consideration, and regard loosened something inside me. The emotional noose twisted around my throat by the symptoms of cancer, a diagnosis of mental illness, and the grief of abuse unraveled.

While the students bore witness to the wound on my chest, they also mended my heartbreak. They were an antidote to all the ways my humanity had been stripped away. And in choosing to pose, I had authorized a new way to be seen in the world—as real, raw and vulnerable.

When the class was over I walked around the room and studied each image. The paintings were so different. Some were in high contrast colors of red, yellows, and blues; others were somber, muted with hues of gray. There was one pastel. Only one student painted the seventeen-inch path of my mastectomy scar that moved from my right armpit to my breastbone. Some students painted one breast and some did not paint breasts at all.

The students had transformed my loss into eighteen soulful images—each one different from the next. In giving myself over to these students, I had allowed them to breathe new life into me.

***

In 2002, after I had posed for two classes of students, Professor Brown asked if he could paint me. Though my husband was against it, and I felt more trepidation than I had about posing for his class, I said yes.

Stephen’s completed painting became part of an art exhibition at The Forum Gallery in New York City. He did not want me to see the painting prior to the opening of his exhibit; by the time I walked through the door of The Gallery, my legs were Jell-O.

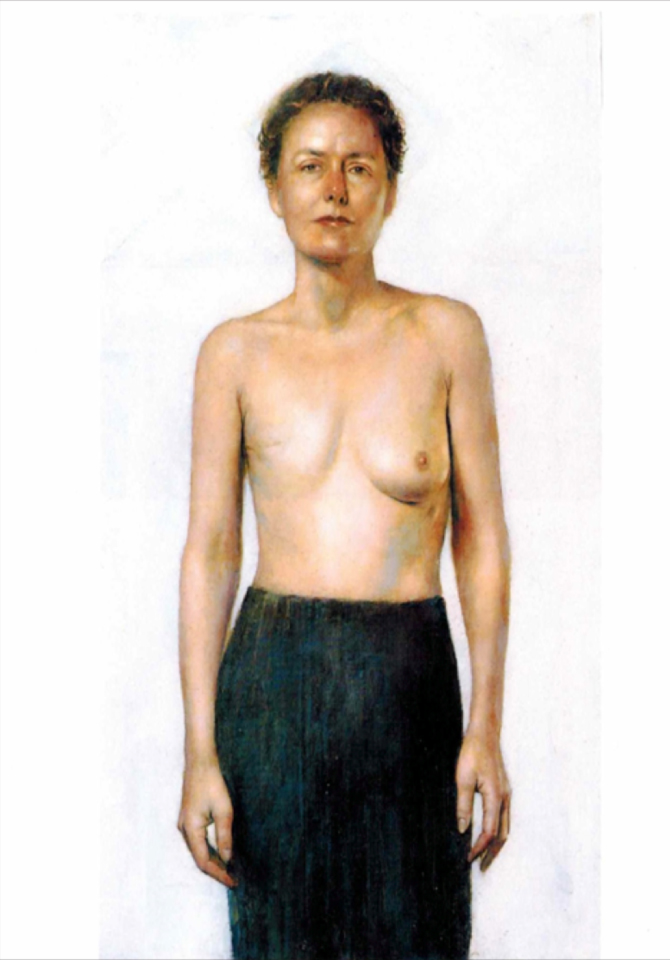

Stephen took my hand and guided me to the main Gallery. There he pointed to a 25 &fract12; x 14 &fract14; inch oil painting on a wooden panel titled “Laura.”

Although I had posed for Stephen nude, his painting of me was not. In his work, I am naked from only the waist up. His “Laura” is half-veiled. She is semi-nude in in a black skirt that might just as easily be a shroud. There is honor, mystery, and paradox in the juxtaposition of the black skirt and the one-breasted, white-skinned woman. “Laura” stands squarely before you with a shoulder jutting out into the world—bearing witness—her gaze meeting yours. Her left hand moves towards you out of the plane of the picture.

The painting shows me in a moment in time when I was filled with despair. When I looked at the painting I recognized that in some ways I had healed from that woman on the canvass. Yet, parts of me still carried heartbreak. What was healed and what was broken existed side by side in my body just as they did in the image.

Stephen Brown called me late in 2006 with good news. “You’ve found a home.” “My painting of you is now in the permanent collection of the Springfield Museum of Fine Art in Springfield, Massachusetts.” The write-up in the Museum’s newsletter read: In the painting, “Laura” is nude from the waist up. It is the portrait of a woman struggling to come to terms with the loss of a breast, her sexuality, her femininity, and beauty. Ultimately though, the picture is about beauty, strength, the triumph of survival and this woman’s irrepressible spirit.”

Healing is not an individual experience. I believe witnessing is essential to healing and in this case, my witnesses were the students, the teacher, the friend who suggested the posing and the participants at The Forum Gallery opening. They are also each person who views the painting that now hangs in the art gallery. Each witness offers the genius of their own healing.

Stephen Brown’s painting is both witness and testimony to the fact that I am not the sum of the worst things that happened to me. Anyone who looks deeply into “Laura” can see the medicine in the wound. The students and Professor Brown helped me learn to carry the beauty and the wounding side by side, moment by moment. I saw that I could not become one who heals without being seen also as one who carried the physical, spiritual, and emotional wound.

I have made several trips to the Springfield Museum to see “Laura.” Each time I witness her I am different. And each time “Laura” looks back at me I am made whole in a new way.

Laura D. Bellmay is a retired fundraising and development consultant. She began writing for the love of the craft after her first cancer diagnosis in 1996. She won the “Best of Letters to The Editor” from The Hartford Courant in 1991. Laura was featured in a series of articles in The Uxbridge Times in 2006 and her essay “Into the Garden,” about coming to terms with her mastectomy after a recurrence of breast cancer, was published in the 2011 Winter Issue of Barefoot Review.

Notes:

Stephen P. Brown died at the age of 59 in Granville, MA on October 21, 2009 after a long journey with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. He was a full professor at the Hartford Art School, University of Hartford. He won an Academy Award for painting from the American Academy of Arts and Letters in New York and was a member of the National Academy of Design, New York. His paintings are in the collections of Hofstra Museum, NY, Albany Museum, GA, New Britain Museum of American Art, CT, Springfield Museum of Fine Art, MA, Speed Art Museum, Kentucky, New York Academy of Design and the Mattatuck Museum, CT.

Want to comment on any Issue of Dark Matter, fill out the form here.

Copyright © 2014-2021 Dark Matter: Women Witnessing - All rights reserved to individual authors and artists.

Email: Editor@DarkMatterWomenWitnessing.com

Please report any problems with this site to webmaven@DarkMatterWomenWitnessing.com