Melissa Kwasny, Poetry Editor

In these precarious times, when so many of us have lost, and are losing, so much, whether beloved people, animals, plants, or the earth as we know it, it seems appropriate for Dark Matter’s latest issue to be devoted to ancestors: naming them, grieving them, and remembering them, which is one of the holy tasks of the living. We are all, in this sense, as J.J. Kleinberg says in her visual poem, “strangers in common.” The poems offered to you here, in their courage to face and honor the dead, in their ritualistic and incantatory use of language and syntax, in their unanticipated access and attention to the interior from which both grief and memory come, seem to me particularly valuable to this moment.

Sheryl Noethe

skull as lantern

Cold didn’t bother us we lay there all night

moving through this incarnation into sand, or glass

I perfumed her and sang in her neck

It was not yet light when her breathing

hoarsened and when the bliss took her away

I wrapped her in white linen blankets

carried her onto the long boat

pushed it in the water and set it afire

sailing in the wind toward Valhalla

But first there were a number of events:

gravity gently smoothed her face and her skin cooled

she paled and became the same color as the sheets

white light blasted from behind her closed eyes

She became the women of every generation

I could see them in her bones

she took me back to the Norse goddess

whose skull she gave me

made from her own teeth

lantern of evolution

only available at the dying

Notes:

My mother and I struggled mightily for most

of my life. When my father died she became vulnerable

and available, and we spend many nights and later

afternoons face to face in her bed. The night

she passed was monumental in my experience.

She changed and cooled and I held her in my arms.

As her face changed I could see one thousand

Norse women in her luminous passing. She introduced

me to life and also to death.

Bio:

I was born afraid and stayed that way for a long time.

Hiding in closets with books was my real world.

Poetry gave me a life I’d never imagined.

I’ve published five collections of poetry and one

teaching text. I founded and serve as Artistic Director

of The Missoula Writing Collaborative, and was

Montana’s poet laureate from 2011-2013.

I am assembling a new manuscript named

“The Science of Co-incidence.”

I’m honored to be a contributor to this journal.

M.L. Smoker

The Book of the Missing, Murdered and Indigenous–Chapter 1

—For Natalie Smoker

The winding cord of highways, unkempt

gravel roads and the trails of animals–

a record of who and what has passed over,

an agony of secrets.

In the end, they have all borne witness,

eyes like glass beads that can never blink.

The dull light of motel neon shines ominously.

An engine growls across the landscape.

Brittle men who are splintered like glass

thrown from a second story window

and we are the room they leave behind.

They are pathetic husks, feeble in spirit.

Fragments fall along fields and shallow ditches,

in overlooked alleyways or underpasses.

A cold, empty breeze rising from the debris.

The first and last moment of her.

It is rage that pulls her up from this place.

She spews out the wretched and miserable

as particles of dawn-lit soil illuminate her skin.

Her hair is a two-edged sword.

She stitches together the collective story of origin,

her body a map: descended from the stars,

on the backs of animal sisters,

carried to safety in a bird’s beak.

This poem was originally published in Living Nations, Living Words, edited by U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo (W.W. Norton & Company 2021).

Notes:

Writing “Book of the Missing…” was an incredibly difficult journey for me. The impact these circumstances have on Native communities runs deep and has impacted so many people I know, including my own family last year. I wanted to try to find a way to return power. To bring back the essence of who these people are. And to let them know we will never forget.

Bio:

M.L. Smoker is a citizen of the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes. Her family’s home is on Tabexa Wakpa. She is the author of a collection of poetry, Another Attempt at Rescue. She earned an Emmy for her work on the PBS documentary Indian Relay and in 2019 she was named to a two-year term as one of two poets laureate for the state of Montana.

Sandra Alcosser

Looking for Her

Leaves newly fallen, did her head dust them?

Tips of fireweed bitten and bitten

Bits of fat and fur, lean and feather

Fragments of an absence not really there—

To find a mother on the planet

Read the clouds that hang above it

Ride down the shadblow and sallies

Become a body grazing on its knees

Looking for her, I kneel down this way

Inhale the coppery sheen below my face

Sniff deeply into a print, then twigs

Where the scent passed, tearing spiders’ rigging—

Without proper instinct to follow

Thoughts rush over, wrap her in shadow

Animal

I’d become one who knew the weight

Of silence by its breath, its press and length

Furtive shy being who sleuthed

The night in search of what remained aloof

Call down the animals, draw deeply

Into furrows, know reedy from grassy

July in the canyon I flick on a light

Inside the tent and begin singing –Outside

The canvas wall, something breathes against me

Then bark at the silhouette of my body

An elk has calved below, beside the creek

Under an arch of branches, escaped up scree

With gashes more than tracks where hooves tore moss

From rock, then left behind a deeper hive of darkness

Tremble

Is she what you looked for? What if you don’t know—

Motherless — does that frighten you most?

Tremble tree, quaker leaf, shepherds carved bodies<

On aspen bark to express their lonely

Nights they danced this grove, its soft cavities

Nights the grove danced upon their bodies

Its rich forest floor of grasses and forbs

Lupine and snowberry, lambsquarters

Thrilling consciousness of Persephone

Female buds crowd together, sticky

Leaf hoppers cast transparent shadows through green

Caterpillars stretch frameworks of silk skeins

Up and down the branches a grove shimmies

Bathes in the sweetness of each other’s honey

Marrow

Imagine flesh so thin that even clothed

Marrow remains visible within bone

How many nights search for someone wiser

stronger , before I come upon her —

An old woman in an inflatable

Yellow raft, a small turquoise lake

Full moon dimpled water of fish rising

To a new hatch and snapping night

Hawks – a woman who cares no longer

For worldly matters , and waiting for her

On shore, a pack animal, a llama

The one they call the little camel

Beside the fire where they will eat dinner

Its four soft pads splayed like ballet slippers.

Notes:

Simone de Beauvoir writes of her father in A Very Easy Death: I had stayed by him until the time he became a mere thing to me: I tamed the transition between presence and the void. With my mother’s death, it was not the transition but the void that needed to be tamed, and though it’s been sixteen years, I doubt I’ll ever be successful. Looking for Her is a sonnet sequence that began when, in the mirror, I saw clearly my departed mother and her sisters, and knew, only by touching my own face would I be close to them again. We survive as mammals because of the nurture of a mother or someone who assumes that role, and the cosmos and everything in it is our first true ancestor. We arrive as a gift from the animals, plants, minerals from which others before us have evolved. In addition to literary scholars, I work with wildlife biologists, and they inform the empirical path of what has proven to be a late-life adventure in the art of detection.

Bio:

Sandra Alcosser’s poems have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Paris Review, Ploughshares, Poetry and the Pushcart Prize Anthology.She received two individual artist fellowships from National Endowment for the Arts, and her books of poetry, A FISH TO FEED ALL HUNGER and EXCEPT BY NATURE, received the highest honors from National Poetry Series, Academy of American Poets and Associated Writing Programs, as well as the Larry Levis Award and the William Stafford Award for Poetry. Her four artist book collaborations with Brighton Press have been exhibited internationally and reside in museums and special collections including The National Museum of Women in the Arts and Musee d’art Americain Giverny. She was the National Endowment for the Arts’ first Conservation Poet for the Wildlife Conservation Society and Poets House, New York, as well as Montana’s first poet laureate and recipient of the Merriam Award for Distinguished Contribution to Montana Literature . She founded and directs SDSU’s MFA each fall and edits Poetry International.

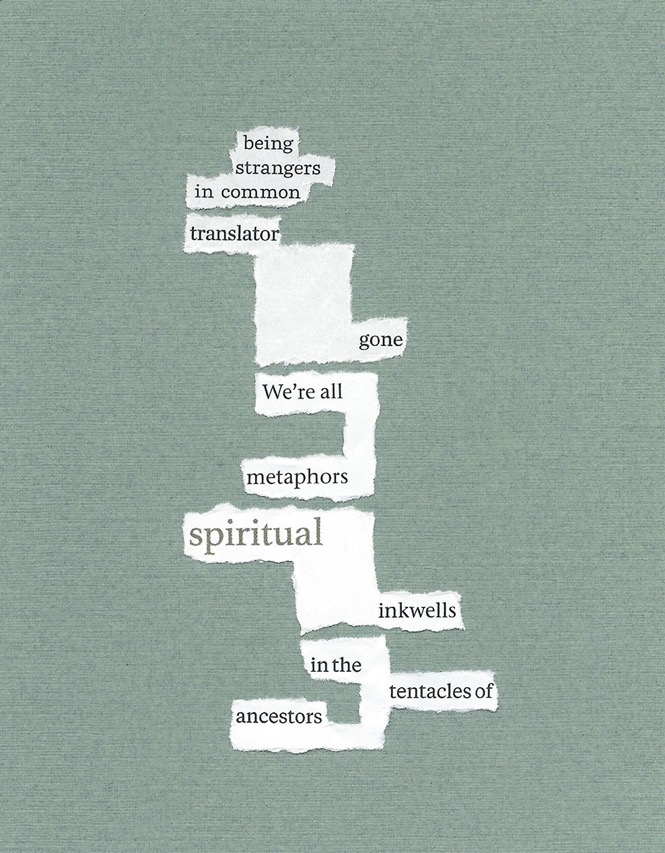

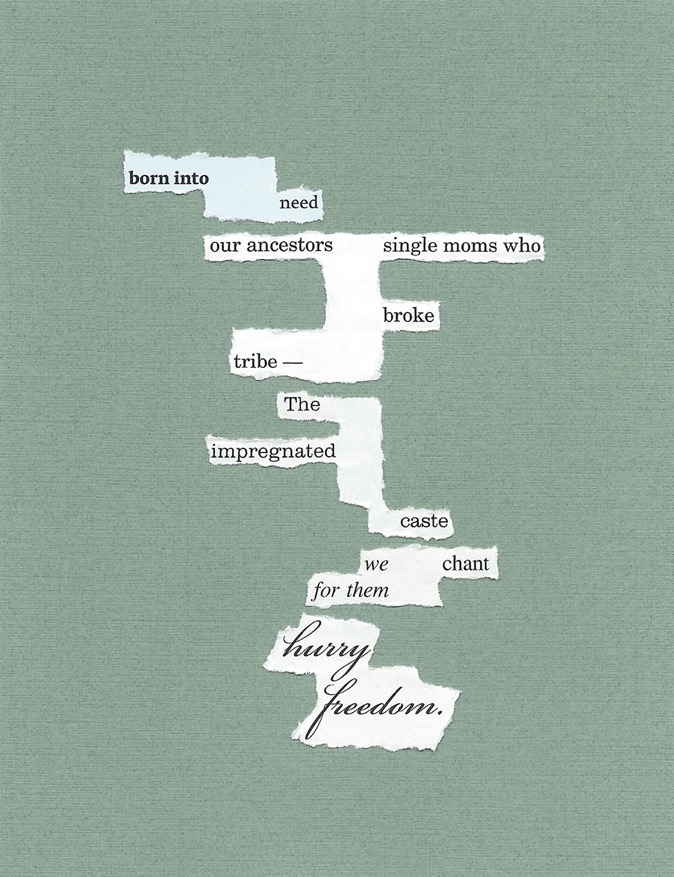

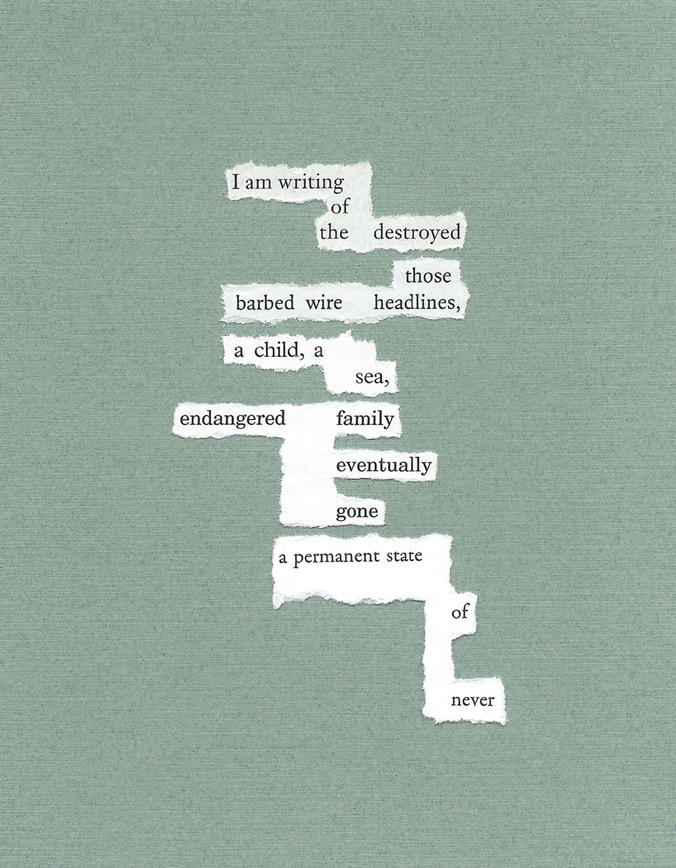

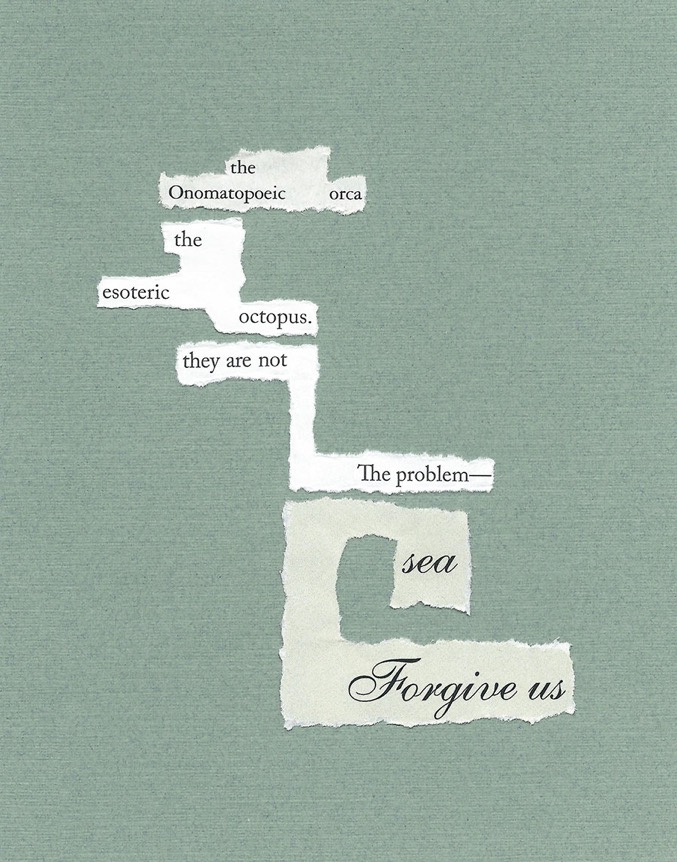

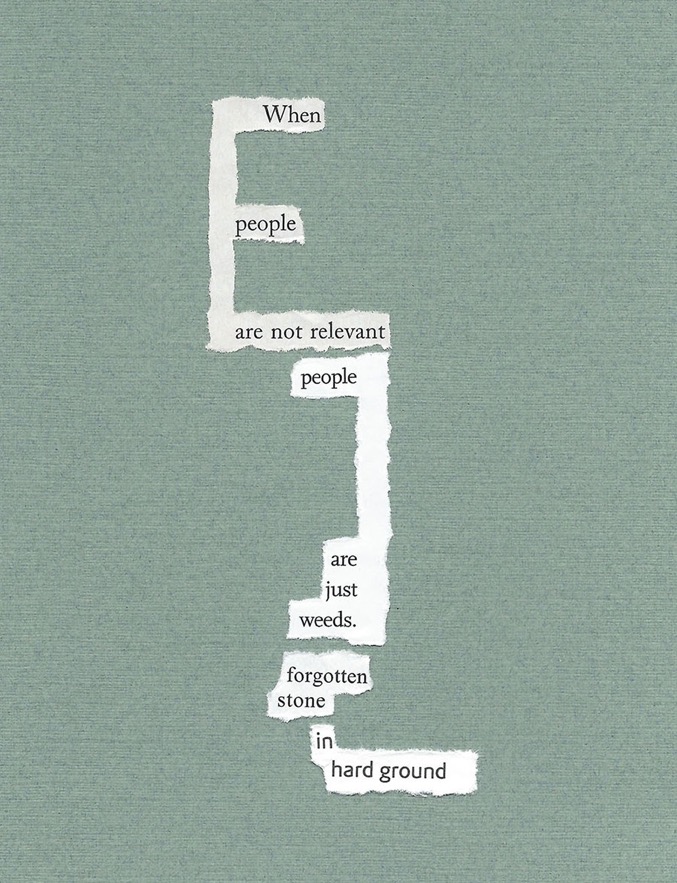

J. I. Kleinberg

Five Visual Poems

being strangers

born into need

I am writing

the Onomatopoeic

When people

Notes:

These pieces respond to a profound sense of loss—personal, familial, and environmental—and through the medium of found poetry attempt to (re)assemble a coherent narrative.

These visual poems are from an ongoing series of collages (2400+) built from phrases created unintentionally through the accident of magazine page design. Each contiguous fragment of text (roughly the equivalent of a poetic line) is entirely removed from its original sense and syntax. The text is not altered (except for the occasional deletion of prefixes, suffixes, or punctuation) and includes no attributable phrases. The lines of each collage are, in most cases, sourced from different magazines.

Bio:

J.I. Kleinberg’s visual poems have been published in print and online journals worldwide. An artist, poet, freelance writer, and three-time Pushcart and Best of the Net nominee, she lives in Bellingham, Washington, USA, and on Instagram @jikleinberg.

Ysabel Y. Gonzalez

Origins

Lucia, purveyor of ripe mangoes, overseer of rivers,

begot Hilda, priestess, dreamer, whisperer, gem keeper,

who begot her only daughter. Named for royalty,

I’ve been a slave to invention, newness, unyielding boxes

holding a body which I’ll never get back—

young woman I wish I could claim but never owned.

That is her beauty: infinite reckless spiritualist in love with a God

that’s been kind.

The young woman was once a girl, friendless, but loved

by her mother and father like an animal who mouths their cub

by the scruffy neck. The girl did not know how to dress.

The girl did not know how to comb her hair. That is the price

you pay for loving pages in a book—you live messily.

But the girl knew other things: Disney and radio songs

and a bird in a pink cage that hissed through his bars. She loved

creating and storing alternate versions of stories in her brain.

Like that time during recess when the school boy walked up concrete steps

leading inside, leaned over and spit on her puffy coat. It was such a cold

day. Couldn’t the white have been snow on her shoulder?

And what of the way she walked? Hunched, hoping she would crumple,

her body disappearing into smallness, whiteness, plainness.

She imagined all the ways she could save her body from being looked at,

eyed, devoured. She knew, too young, how a body could get a woman

in trouble. It’s my fault for constructing myself this way was the pervasive

thought echoing in her little girl-brain.

The girl, the young woman, forgives herself and is hopeful,

like Disney, like radio songs, but not like the hissing bird. The woman

now, is forgetful. Remembers how to create, but forgets how to love

her body. Men used her to feel alive and she allowed it because

her mother’s advice, about love, was garbled,

words on the tip of her tongue she can’t quite recall.

She decides, this is the end

and surrounds herself with women.

Women who love her, guide her, pick her up and instruct her to be patient

until she can hear the music again, the words again, trust

her body again. Hear her mother. She does. It’s glorious,

and everything you’d imagine: angels’ iridescent wings flapping,

the earth rotating more quickly, and even—yes—soft kittens purring

on a pillow. It is raucous. It is peace.

Origins should never be taken lightly, they feed the ego or starve it,

creating a woman boundless or shackled. Sometimes, somewhere

in the middle. Ysabel was born to warrior women, but had to learn it all again,

the same lesson over and over like Caribbean water rushing in on sand,

drawing back to reveal creatures hiding in their shells.

When I evoke my start, I taste salt, it calms me. I taste power too,

rough boulders washed over by ocean, instructing me to be formidable,

believe in their rocky boldness.

This origin is for you—the believer, the rebel, the odd woman out.

Maybe yours is a little like mine—

daughter of a goddess, birthed with a bit of fire flickering from the eyes.

Chameleon or Thinking About My Mother the Sparrow

Chirrup caught in its jewel-throated song,

she is the sorrowful sparrow flitting above,

leading me although she doesn’t quite know the way.

This is no dream and I’m grateful

she’s flying and I can see her from the ground.

Sometimes I hear her story better

when I tilt my head slightly—

the sparrow’s melody is a siren. Now

a bruise. Blade rising. Now

a clue to how to move in this world,

sort of trembling (some say dancing).

Her music is my own and I inherit the achy

sword and swerve, even when I’m unsure it will serve me.

Every day my body morphs, colors rippling

over like tidal rainbow, giving me hope and exhaustion,

molding to the world as it holds my skin in its hands.

I take comfort in any spritely creature broken yet full of faith,

but especially this sparrow, who believes her spell will guide me to where

the universe needs me to stand. I’m right

where I’m supposed to be, mother, getting rained on.

The sun will dry me up, will fill

my cupped palms with light.

It is dawn again and I should rest from all this singing.

Sit with today. Tomorrow

will come and I’ll wonder, wander through it then.

Notes:

Origins. This poem holds in its hands two leading women in my life–my mother (living) and grandmother (who has passed), both of whom continue to guide me. Because of their ancestral inspiration, I feel fuller, happier–and 100% braver.

Chameleon or Thinking About My Mother the Sparrow: Chameleon is a persona I’ve developed who is constantly thinking about changing, shifting, and adapting to and with the world. Here she sits and thinks about her mother, who is different yet ancestrally, the same.

Bio:

Newark, NJ native Ysabel Y. Gonzalez received her BA from Rutgers University, an MFA in Poetry from Drew University and works as the Assistant Director for the Poetry Program at the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation. Ysabel has received invitations to attend VONA, Tin House, Ashbery Home School and BOAAT Press workshops. She’s a CantoMundo Fellow and has been published in Tinderbox Journal; Anomaly; Vinyl; Waxwing Literary Journal, and others. She is a Pushcart Prize nominee and the author of Wild Invocations (Get Fresh Books, 2019). You can read more at www.ysabelgonzalez.com.

Mariana Mcdonald

Post Mortem

Dissection of aorta:

the severing of the soul

from all that once was

blood and bone

and in the cleft

made whole,

in spirit

and god’s company.

Thus hallowed,

yet no good

for one who wants

to feel her hand

in all its

bone and blood

Notes:

Our ancestors have all transitioned at some moment from a being planted on the earth, to a spirit of the earth. When the ancestor is a beloved family member, the transition can be wrenchingly painful. My sister died suddenly and unexpectedly when her aorta tore apart like an old tire, plunging me into the depths of grief. “Post Mortem” expresses the profound longing that we the living have for the dead.

Bio:

Mariana Mcdonald is a poet, writer, scientist, and activist. Her work has appeared widely, including poetry in Crab Orchard Review, LunchTicket, and The New Verse News; fiction in About Place Journal and Cobalt; and creative nonfiction in Longridge Review and InMotion._ She co-authored Dominga Rescues the Flag/Dominga rescata la bandera, about Black Puerto Rican heroine Dominga de la Cruz. Mcdonald lives in Atlanta.

About the Author

Melissa Kwasny is the author of six books of poetry, most recently Where Outside the Body is the Soul Today (University of Washington Press Pacific Northwest Poetry Series) and Pictograph (Milkweed Editions), as well as a prose collection, Earth Recitals: Essays on Image and Vision (Lynx House Press). She is the editor of Toward the Open Field: Poets on the Art of Poetry 1800–1950 (Wesleyan University Press) and co-editor, with M.L. Smoker, of the anthology I Go to the Ruined Place: Contemporary Poets in Defense of Global Human Rights (Lost Horse Press). Recently published by Trinity University Press, Putting on the Dog: The Animal Origins of What We Wear is her first book of nonfiction. She is currently serving as Montana Poet Laureate, a position she is sharing with M.L. Smoker.

Return to top