We are about to destroy each other, and the world, because of profound mistakes made in Bronze Age patriarchal ontology—mistakes about the nature of being, about the nature of human being in the world. Evolution itself is a time-process, seemingly a relentlessly linear unfolding. But biology also dreams, and in its dreams and waking visions it outleaps time, as well as space. It experiences prevision, clairvoyance, telepathy, synchronicity. Thus we have what has been called a magical capacity built into our genes….To evolve…—to save ourselves from species extinction—we can activate our genetic capacity for magic.

Barbara Mor, The Great Cosmic Mother

Welcome to issue #2 of Dark Matter: Women Witnessing—“Fragile Ongoing.” The stage for this issue is set by Jan Clausen’s “‘In this Moment the World Continues’: Under the Sign of Species Suicide,” originally a keynote address, which exposes the dark matter underlying all artistic endeavors in this time. “The experience of a type of collective insecurity never known before in our history as a species is the contemporary context for all writers’ inventions, whether or not we acknowledge it,” Clausen contends. In “When Earth Becomes an ‘It,’” Robin Kimmerer puts it even more starkly: “We … stand at the edge, with the ground crumbling beneath our feet.” How else to go on but with, to use Clausen words, “an open balance of unbearable danger and tender possibility.”

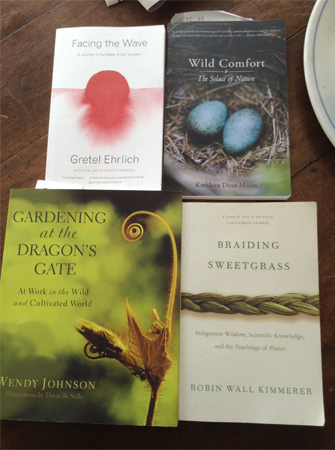

Kimmerer’s piece, and Kathleen Moore’s “The Rules of Rivers,” are excerpted from opening addresses they gave at the “Geography of Hope” conference I attended in mid-March. I’d been attracted to this conference by the focus, “Women and the Land,” and the roster of extraordinary writers (ptreyesbooks.com/goh). Admittedly, at the end of a long winter in Montreal, the location—Point Reyes, California—was also a factor. I did have some reservations about a conference called “Geography of Hope” (I’ve since learned they’re the last words of Wallace Stegner’s “Wilderness Letter,” written in 1960), imagining regular injections of uplifting, morale-boosting rhetoric. But there was nothing of the kind. In the opening panel, Gretel Ehrlich choked back tears as she spoke of her hope—which she said comes and goes like the ice sheet in Greenland she has been visiting regularly since 1993. “We are falling into another world,” she said; “We are in a new climate land. I’m like a metronome oscillating between laughing and crying all day long…” Kathleen Moore sounded a similar note: “Yes, we are caught up in a river rushing toward a hot, stormy, and dangerous planet. The river is powered by huge amounts of money invested in mistakes that are dug into the very structure of the land, a tangled braid of fearful politicians, preoccupied consumers, reckless corporations, and bewildered children – everyone, in some odd way, feeling helpless. Of course, we despair. As a philosopher, however, Moore also spoke in favor of a moral abdication of both hope and despair.” “Matching our ways of living with our deepest values,” she said, “is way better than hope.” “Hope,” in other words, was not something any of the opening speakers seemed to be able or willing to confidently embrace.

still not seeing them

still not seeing themBut it is hard to feel gloomy in Point Reyes when the sun is shining and the coastal headlands are deep green and there are red-tailed hawks soaring and gray whales breaching and elephant seals lolling on the sand. On the first day of the conference—one of many clever moves on the part of the organizers (the conference is sponsored and coordinated by Point Reyes Books)—all participants were sent outdoors on field trips. We were dispatched in groups of fifteen, each with a resident expert, to farms, beach, wetlands, riverbeds, dairy ranch—in the case of my group, to the marine headlands, where fog lifted just as we reached our look-out (enabling me to see my first whales ever). In other words, we were thrust into communion with some small part of the land before taking our seats on folding chairs indoors to listen to talks about the land. We returned from our forays bonded with the flora and fauna of this place, flushed and shimmering and full of stories about what we’d seen and felt and heard. To be among women who know and love the land deeply and intimately was itself one of the great gifts of this conference.

“Aren’t there other ways to live, and how do we invent them?” Clausen asks in her talk.The question goes to the heart of this issue of Dark Matter. A grammar of animacy is something every piece in this issue could be said to be aspiring to, if not enacting (quite literally so in Alexandra Merrill’s “Homage to Bees”). Humans in these pages carry on eloquent and instructive conversations with earth intelligences of every kind: with the rain, with a wolf, with dragonflies, with bees, with squirrels, with cardinals. “After all that has happened, we are still connected,” writes Joan Kresich in her letter of apology to a Yellowstone wolf.

In our first issue, elephants came in a dream to teach us about grieving (Issue #1 Grieving With the Elephants -Kristin Flyntz), and here they are teaching us again, in both “trinkets” and “The Music of Grief.” In “Dreaming the Future,” Valerie Wolf points out that “The plants have been on this planet more than 450 million years, the animals have lived here more than 350 million years. Humans, in their current form as homo sapiens, have only dwelt here for 220 thousand years. Who should know more about what works here?” It is understood by the writers here that we have everything to learn from these other intelligences. (And, as Kimmerer points out, “We could use teachers.”)

There’s an intricate pattern of rhymings and concordances in the material gathered here that should perhaps not have surprised me. It was striking, for example, how many of the pieces were either a meditation on or an outcry of grief, if not both. And in just as many, a call is being answered—from a dream, from spirits, ancestors, or animals—a call that shows the writer where she needs to go, and often leads her somewhere unexpected. But there is call and response within the issue itself, most obviously in the anguished longing for ceremony for roadkill in Gillian Goslinga’s “To Witness” which is answered so concretely and beautifully in Carolyn Flynn’s “Grandmother Squirrel.” The Mourning Feasts Cynthia Travis hosted for grieving communities in post-civil-war Liberia are echoed in Ruth Wallen’s “Cascading Memorials,” installations that enable public, communal mourning for the landscapes we are losing.

Though the writing in this issue seemed to constellate around the categories of “Grieving” and “Guided,” that’s not to say there is not plenty of grief in the ‘Guided” pieces, and vice versa. And, as more than one of the writers here points out, grief itself can be a guide. Travis writes: “Proper grieving is one of the key indigenous technologies that open the doors between worlds.” I’m sure I’m not the only one to have noticed that when I fall on my knees and ask for help—not always, but often—it miraculously comes, though not necessarily in the form I expected. It’s worth noting that the women in Deena Metzger’s dream in “Dreaming Another Language: She Will not Kill” come to her because she’s been been praying for rain—because she’s been asking, on her knees, “what is to be done, what is to be done, what is to be done?”

Kristin Flyntz, whose expert copy-editing skills have been applied to most of the pieces collected here, wrote to me once she’d gone through the bulk of them to say that it felt to her as if “the intelligences, the teachers and the knowing that we desperately need have deliberately gathered in this issue, both in their human form (the writers) and in those who are working through them. Perhaps we are being shown, collectively, where we need to go in order to live in alliance with all life…” Reading these words I felt, it is so! Just as all of the writing here is informed by the understanding that our continuation on this earth hangs in the balance, all of it can be read as a response to the questions: “Are there other ways to live?” and “What is to be done?”

Barbara Mor, a friend and collaborator of many years and author of the epigraph above, drawn from her landmark ecofeminist book The Great Cosmic Mother, died unexpectedly in January of this year at the age of seventy-nine. In the fall, I had an exchange with Barbara about this journal-to-be. Initially I’d written to ask her permission to use the title, since I discovered, only after I had decided on it, that she had a blog called Dark Matter/Walls. Barbara gave me her blessing for “Dark Matter,” but in October, when I sent her the link to our website, she wrote to me with misgivings: “Post GCM (The Great Cosmic Mother),” she wrote, I had enough of those NewAge women who were immersing in their version of dreams & visions to escape (in my opinion) the disciplines of history & the chaos of politics. I think our dreams & visions need to be grounded in the horrors of ancient & current realities; & that it is time to retrieve the polemical Fist, if not my version then someone’s somewhere.” Barbara’s uncompromising fury on behalf of women and the earth has been a touchstone for me all these years; she has always embodied the kind of fierce protectiveness Laura Bellmay, in “A Call from the Edge,” says we urgently need. So I took these words of Barbara’s to heart, and do even more so now that she’s an ancestor.

There is no question that all the dreams and visions in this journal have been and are grounded in “the horrors of ancient and current realities,” and I hope that rage, and outrage, will always be seething not far from the surface on this site. (Interestingly, the cause of rage was taken up at the “Geography of Hope” conference most adroitly by longtime Buddhist practitioner Wendy Johnson, who spoke of anger as the “refiner’s fire” and cautioned us: “Don’t be too nice, it’s overrated. And there isn’t time.”) As for retrieving the polemical fist…well, our version may not be quite as antagonistic as Barbara would have liked, but the fist is there. Perhaps it’s tempered by the recognition of our fragility. And also by an understanding that the fist, like the heart, does also need to open, even when we’re confronted with atrocities. A Liberian peacebuilder who worked with child soldiers and warlords in Liberia’s civil war advises Travis: “…We must deliberately move into the field and lavish love on those incapable of loving.” And to the violent young man in her dream in “Dreaming the Future,” Valerie Wolf says, “A part of me wants to lean in and help you change.”

At the end of Wolf’s piece, a dancing girl in her dream creates a magical pathway to the spirits. It’s one of many instances of dancing in this issue. Judy Grahn’s dragonflies dance. So does Deena Metzger’s rain. Even trauma, at the end of “The Music of Grief,” gets up and dances. Despite the horrors of ancient and current realities. And because of them. This dancing Barbara Mor would have understood, and applauded. “…the universe…is the first dancer,” she writes in The Great Cosmic Mother, where she reminds us of “the first circling dances of molecules, of atoms, of quarks around the cosmic spiral.” Dance takes us “back to an original communion with sheer evolutionary energy.”

Barbara’s fist was raised, always, in the name of communion, connection: “We must remember the chemical connections between our cells and the stars, between the beginning and now.” Are there other ways to live? What is to be done? I give Barbara Mor the last word in this editorial, as I did the first one. “We must remember and reactivate the primal consciousness of oneness between all living things. We must return to that time, in our genetic memory, in our dreams, when we were one species born to live together on earth, as her magic children.”

Lise Weil

Montreal, April 2015

Return to top