when I swallow

moisten my lips

trace my tongue

along my teeth

taste my sweat

lick my blood

feel the opening

to the soft cavern

inside of me

there is water

Two summers ago, I was invited to a women’s dream council held on the shore of a tiny, secluded lake in Quebec. Conifers and deciduous trees encircle the lake whose depth plummets nearly fifty feet. Solid outcroppings of Canadian Shield offer places to lie on sun-warmed granite. A resident beaver plies through morning mist, her wake splitting the lake in two. Deer bark at night, birds and insects offer songs. Wind willowing off the lake feels like effleurage.

At the beginning of the council, we asked for guidance from the lake and woodlands to help us answer the question “How can we best serve the natural world?” After four days of listening – of dreaming together, calling in spirits, swimming at dawn, and meditating by the fire under a canopy of firs – the seven women present heard the answer.

“Be with me.”

I packed up that response with my tent, and en route home, a blinding rainstorm blackened the sky, wind rocked the car, thunder resounded in my chest, and lightening lifted the hair on my arms while I sat in commuter traffic on Pont Champlain in Montreal. The St. Lawrence River ran underneath me, and rain flung itself down so intently that I could barely see the car in front of me.

Water everywhere.

Oddly, I felt at ease. I opened my window, extended my arm into the storm and let the rain and wind penetrate my skin. Back inside the car, streams of water snaked down my arm and dripped off my fingers. I brought the back of my hand to my lips and sipped.

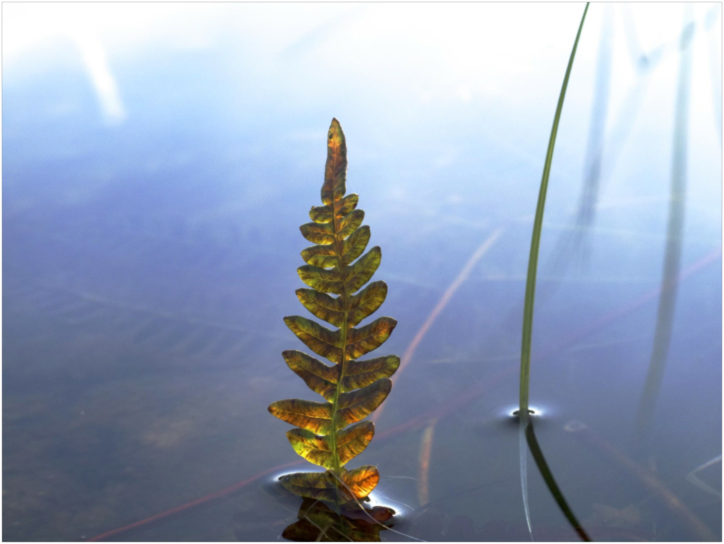

A year after the dream council, while reviewing my photography files, I realized many of the images I had taken since those days in Quebec included water – vernal pools, streams, ponds, reservoirs, rivers, waterfalls, lakes, and ocean. As I opened file after file, I saw that my camera and I had been with water so frequently that there were over a thousand pictures of water. Artifacts from a vigil I was not aware I had been keeping streamed across the screen.

Out of those photographs, I selected 112 and made tiny 2″x2″ prints, easy to slip into a wallet or a pocket as a keepsake, a memento. While working with the images, I recalled that 1-1-2 is the toll-free international number that can be dialed from mobile phones to contact help in an emergency. I thought how apt, given that water and all elements and beings on the planet currently live in a state of emergency, a healing crisis that is human-made.

In some systems of numerology, the number 112 indicates the desire and capability to move forward with motivation and intention. The Water Protectors at Standing Rock showed us the sweep of their purpose, the depth of their determination to be with water. In making a stand on the Missouri River with the vast strength of their presences, they knew what it would mean to heal. Their courage broke and then mended my heart.

Seeing water in partnership with my camera has shown me that no action on behalf of water — or in consort with any element or being alive on the planet with us – is too small. Water needs our full attention, our wakefulness, our presence—and I am trying to give it mine.

About the Author

Anne Bergeron, M.A., I.M.A., is a teacher, writer, and Thai Massage therapist who lives in Corinth, Vermont. Much of her writing explores rural living through the lens of our changing climate. Anne lives off-grid on a homestead that she built with her husband, where she tends gardens, sheep, and chickens. She also teaches yoga to people of all ages, and is a 2011 recipient of a Rowland Foundation fellowship for her transformative work in public education.

Return to top