October 2016, Issue #4

Making Kin: Part I

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Editorial

Lise Weil

Cynthia Travis

Listen with Your Feet

Jennifer Finley

Deer

Magpies

Magpies

What My Cat Would Say to Me

What My Cat Would Say to Me

Karen Mutter

Kinship and Murder

Melissa Kwasny

Another Letter to the Soul

Deena Metzger

Becoming Kin—Becoming Elephant

Kyce Bello

Correspondence with the High Country

Correspondence with My Garden

Correspondence with My Garden

Canticles of Drylands

Canticles of Drylands

Dominique Mazeaud

Material is Matter…is Mother

Kim Chernin

A Stuttering Kind of Worship

Nancy Windheart

Saved by Whales

Susan Richardson

Tope

Patricia Reis

After•Word Dining Out on the Great Divide: Donna Haraway, Thomas Thwaites, Frans deWaal, Karen Joy Fowler, Charles Foster and Helen MacDonald

Grace Grafton

Crow Mother, Her Eggs, Her Eyes

Long Ago They Captured Our City

Long Ago They Captured Our City

Cynthia Anderson

Invoking the Salamander

Sudie Rakusin

Where I Stand

Kathryn Kirkpatrick

She and I

Camille Norton

After•Word Robin Coste Lewis’ Voyage of the Sable Venus and other Poems

Mandy-Suzanne Wong

Ama No Musume

Tricia Knoll

Divorce of the Night Sky

Andrea Mathieson

Listening for the Long Song

CODA

Kristin Flyntz

Embracing Duncan

Lise Weil

Just This

Deena Metzger

Becoming Kin—Becoming Elephant

At the center of empathy and compassionate understanding lies the ability to see the other as true peer, to recognize intelligence and communication in all forms, no matter how unlike ourselves these forms might be. It is this gift of empathy and connection, embodied in the relationship between us and other species that enables us to thrive now and into the future.

Because we share with them the same life force, to know the animal other as worthy, alive and even as a beloved peer is to be truly in relationship with powerful forces of creation itself. To acknowledge and even cherish the intelligence in other forms of life is to sustain our own future. To honor intimacy across the seeming boundaries of species is to return the sacred to the world. We are all the same world inside different skins, and with different intelligences.

From the introduction to Intimate Nature: The Bond Between Women and Animals, edited by Linda Hogan, Deena Metzger, and Brenda Peterson

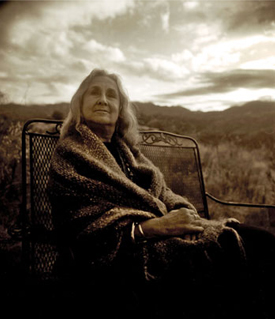

The Ambassador 2008 Photo by Cynthia Travis

The Ambassador 2008 Photo by Cynthia Travis

Kinship means relationship. It could mean family. It implies attunement and long-term commitments to each other. The first time I met the Ambassador Elephant, I said, “I know who you are. You are from a holocausted people and I am from a holocausted people. … I promise you, your people are my people.”

That was seventeen years ago. It was a commitment. We are kin. The Ambassador and his people know this. How else explain that he and his community have met me each of the five times that I have returned to Chobe National Park in Botswana? My agreement is to return to a particular tree by the river at the same hour on the last day of our visit to mirror the original meeting with the Ambassador and his people in 2000. His part of the agreement is to show up in ways that are unmistakable. Each time, we were able to construct a narrative, to find meaning in the elephants’ displays and interactions with us or with each other. Story, we can say, is the medium.

In 1999, the groundbreaking anthology Intimate Nature: The Bond Between Women and Animals that I edited with Linda Hogan and Brenda Peterson, was published. The book established that compassionate and intuitive relationships with animals lead to greater knowledge and understanding than does objective research. Knowledge emerges from relationship. Intimacy informs. Additionally the selections revealed that animals are remarkably and surprisingly intelligent, are spiritually alert and can, like human beings, exercise agency.

It hadn’t been our goal to draw this conclusion; it was not evident until the book was complete. We had intended to look at women’s bond with animals, we didn’t realize we were also discerning animals’ focus and activity. As relationship is reciprocal, the relationships between humans and animals are inevitably reciprocal. In the editing of the book, we had acknowledged that animals are peers but we hadn’t fully investigated the implications. For anyone who read the book attentively, the five- thousand- year Western cultural hegemony of humans over animals was challenged.

After the anthology was published, I visited Gillian Van Houten, one of the contributors, at the wild animal preserve, Londolozi in South Africa. Her story of hand-raising the lion Shingalana and releasing her to the wild is in the anthology, as are stories from many of her colleagues at other reserves in Africa. We tried to make contact with one of the several breeding herds that live at Londolozi but the elephants had, conspicuously it seemed, avoided us. Sighting elephants is commonplace at Londolozi but I was denied connection, which I took to heart. It seemed I was not ready for what I was imagining – not to view, but to sit in council with elephants.

I needed to prepare. That is what I did. In Chobe, Botswana, on Epiphany, January 6th, 2000, my heart and soul were ready.

“Slowly the elephant lifted his head from the grasses and began walking along the river. He did not stop to graze nor did he look around but walked with clear determination and intention....focused, deliberate, determined, conscious, aware intention.

He stopped directly in front of the truck and raised his trunk toward us. It was over and under itself and up and over again. That is, he tied his trunk into an impossible knot…. I was on my knees in the flat bed of the pickup…. My hands were open on the edge of the truck so that the elephant knew that I was empty-handed and that I had no weapons.

In my mind I spoke to him.

“I know who you are and what kind of beings your people are. I have some sense of the extent and depth of your intelligence and development. And I know that you are of a holocausted people ….”

Then I silenced my mind. I had said enough. Humans have said enough.

…The elephant stopped and looked me in the eye. We stayed this way a long time. Ten minutes perhaps....

Then he turned and moved to the back of the truck and faced it. I moved to him and put my hands out again. We looked at each other eye to eye.

…Another ten minutes passed.

…I heard words in my mind and I let them be spoken silently. I promise you….

He turned and went behind the truck as if to disappear up the hill into the brush but turned again and faced the truck and so I turned also and on my knees again, acknowledged him.

...Another ten minutes passed…. The elephant departed, climbing slowly up the hill and disappeared into the trees.

…We did not explain or understand anything except that Amanda Foulger said, “You are an ambassador and they sent their ambassador and you have made a covenant with each other.

It was getting late and one must be out of the park by 7 o’clock. We made our way slowly…

But then we couldn’t believe our eyes. Elephants were coming down the hill and crossing the road to the river. At first only a few females and their babies, but then more of them. Waves of elephants. Waves upon waves. …The elephants continued to come. Dozens of them lined up alongside the river and still more were coming. Bulls and cows, old ones and young ones, babies and adolescents. It was like …it was like the world ended and then it was saved and the animals were coming forth into the new dawn.

…The animals were lined up for a quarter mile as if for a parade…. They were bowing their heads and flapping their ears at us. And we were bowing and waving and saying, “Thank you. And bless you. And thank you. And bless you.”

From Entering the Ghost River: Meditations on the Theory and Practice of Healing, Deena Metzger, Hand to Hand Press, 2002

Despite the anthology, and the surge in writing about animal intelligence and relationships, this first meeting and those that followed1 remain unprecedented. Cynthia Travis, writer and founder of the NGO everyday gandhis, has been my companion and colleague on several of the meetings when the elephants have communicated by enacting a Story, creating a piece of theater that invite us to participate. The mystery increases the more often the elephants appear and the more dramatic their exchange with us. It is as if we are making ‘first contact’ with another species and culture altogether. We are entirely captivated and are trying to understand what the elephants might have in mind with these communications.

Cyndie and I had a remarkable encounter in Tanzania in 2008 that alerted us to the possibility that we were being called into unique relationships with elephants in general rather than with a particular elephant and his people.

We were traveling in the Ruaha, Tanzania, with, for the first time, a guide. We did not know how the presence of a local might affect our connection or whether a relationship was possible outside of Chobe and the elephants we knew. Her son and a companion were with us. Stopping to look over an embankment, we saw a female elephant with several calves in a shallow pool of water in the sand river below. We quietly watched as one of the young female elephants ran to and from the bank alternately spraying water upon us and herself with her trunk. Her action was deliberate and conscious. We stayed engaged until the mother called the calves away, wandering away down the river. Having been given permission to leave, we proceeded onto the dirt road again. Suddenly, a great trumpet sounded. The entire elephant family had come up the road behind us and were closing in on the truck. I interpreted the trumpeting, coming from the young elephant we later named Spirit Sister, as an injunction to stop. I had to heed her demand. The guide who was driving was concerned but yielded to my request. In a moment, we heard another trumpet. A young bull elephant emerged from the trees, stopped and trumpeted before us, then took his place within the elephant family. Spirit Sister was introducing her family to us. We began to consider again that we might, in fact, be Ambassadors between species.

At first we thought that the meeting with the Ambassador in Chobe was privileged, because he and his people met us again and again without having any way of knowing when we would arrive. We also thought it could occur because we were in our own vehicle and free from the opinions, beliefs, and restrictions of the locals. Though the meeting in the Ruaha was not as dramatic and extended as our other meetings in Chobe, it did occur, irrefutably, in another country and in the presence of a guide.

Perhaps because I have returned to Chobe so many times, and the interaction with the elephants has been so personal, I have held the belief that the relationship is between the Ambassador and myself and whoever has joined us for a visit. Cyndie thought that the relationship was between us and elephants, not the Ambassador exclusively. Whatever the means of connection between us, both Cyndie and I have felt called to meet the issue of elephant and animal extinction. A dream in July 2015 furthered this commitment.

Valerie Wolf and I were upstairs in an old Victorian like mansion. [Valerie, Cyndie and I had had a remarkable meeting with the Ambassador in 2008]2 We heard voices downstairs and became alarmed. Two dark skinned men, neither black nor white, revealed they were from the Radical Elephant Movement, a revolutionary network acting to prevent elephant and animal extinction. We were being recruited into the movement and asked to find ways to participate that have never been thought of or tried before. Radical action is what is required. The men faded away but not before they opened conduits to other dimensions through the four directions.

After they left, we noticed a fire in the fireplace in the adjoining library. Two women were entering the room, one through the walls and the other through a tube in the midst of the fire. The woman coming through the wall said she was too sensitive. She had seen elephant culls. She didn’t know if she could …. If she could … what? Go on? Go on with the work? Continue the elephant radical work?

The mouth of the woman in the tube was wide open and her voice or words were struggling to be heard. Her name, Ashanti, was repeated or omnipresent. It is clear: there is something we must do.

On awakening, I knew that we must do everything we can – whatever it is – to prevent elephant extinction. Researching, I learned that the Ashanti were a tribe in Ghana, devoted to elephants, offering dead elephants funerals equal to what they would provide for a chief. Also, they were dreamers. Harriet Tubman, of this lineage, directed the Underground Railroad through her dreams. I had been recruited, through the dreamtime, into a radical elephant network. Cyndie and I determined to return to Africa to see what we could learn. We knew this: We will not be able to think our way to vision. We will have to go to Africa and listen.

Whether it was an individual elephant, his family and herd, or whether the elephants themselves were exercising agency, is something of what Cyndie and I wanted to investigate when we returned in in January 2016, first to Chobe then to Mashatu, a reserve in southeastern Botswana, and finally to Damaraland in Namibia to visit the desert elephants. We wished to know if the Ambassador and his herd were singularly in relationship with us, or whether we might have similar contacts with different elephants in other places. We were always careful about whom we invited to join us on such a pilgrimage and wondered if the elephants would contact us when we were in trucks driven by guides from the area. New rules were being enforced in Chobe National Park. We were no longer able to enter without a guide and even Lynne, the local woman guide, was working under unwieldy restrictions. This visit would test whether we could overcome the greater obstacles to meeting the Ambassador and whether the meetings would be confirming for us and convincing for Lynne and our other guide, Matt Meyers, from South Africa, who had been Head Ranger and Head Photographic Ranger at MalaMala, adjacent to Kruger National Park, one of the first private reserves in South Africa. If the connections with the Ambassador or with elephants were to have impact, they would have to be acknowledged by people who had expertise in the wild.

For our own purposes, we had to find guides who could listen, who would agree to spend two to three hours in silent meditation each afternoon at the Chipungo tree. The guides at the other reserves would have to agree to spend long periods of time in silence without driving and to allow me to direct our activities as long as there was no evident sign of danger. The usual patterns is for all tourist vehicles to converge when there is a sighting -- a leopard, a kill, a rare animal. Then each truck may only be allotted five or ten minutes of primary viewing area before it has to yield its place to others or speed away to see a herd of buffalo, a pack of wild dogs, or a mother cheetah and her cubs. Both Matt and Lynne were very happy to have the afternoon to sit and watch what appeared to us over time instead of chasing around the veldt.

* * *

On a boat trip the day we arrived, we were able to sidle up to the shore where many elephants were splashing in the water.

Exhilarating as it was to watch them, I was hoping, as I had in the past, for some sign that contact would be made on this journey. Soon something called the herd inland and they began walking up the hill away from the river. As we were about to turn away, a young elephant, much like a teenage girl, reversed herself and came trotting down the trail to the water, turned to go back, then stopped and held my gaze, almost coquettishly, for a few minutes. Unprecedented. Lynne, who had only heard a few stories of our history with elephants from Matt, looked at me. “She knows you,” Lynne said. The small connection and Lynne’s confirmation boded well.

Photo by Cynthia Travis

Photo by Cynthia Travis

Driving east the next day, to the original site, I learned that I had to identify the Chipungo tree with certainty, as once we descended to the now one-way river road we could only continue west. If we made a mistake we could not turn back. I hadn’t been to the tree in five years. As everything is always changing in the wild due to river tides, rain, storms, winds and time, I was concerned. Driving along the bluff, we stopped to visit with some elephants coming up a trail from the river. At first, I was taken by the babies cavorting among their mother’s legs as they ascended, but then when I looked down to the bottom, I saw the Chipungo tree.

Thus at the very, very beginning, the elephants and the spirits were showing us where to go; we were entering a field of consciousness with the animals. A first Story had occurred and revealed our meeting place.

For the next days, we encountered different elephants, variously engaged at our common meeting place. We were always grateful for their presence and began to feel that they were revealing themselves to people who had become familiar to them. But on the penultimate day, the elephants, who had gathered at the adjacent water hole, suddenly all left at 5 pm, crossing the river, wandering, virtually disappearing from view.

We were disappointed for there had been some interactions between them that seemed to signal something coming, but now the area was empty, except for a few birds and the hippos, rising, grunting, sinking down into the water. We had made the commitment to stay until six and so we settled down to keep our promise. Then at about 5:40, we were aware of a profound shift. The elephants on both sides of the river that had walked off to the east and west seemingly turned at the same time and began walking back toward our area. Then those on the other side of the river began swimming toward us.

By 5:55, it seemed all the elephants that had been near us that day had returned and were milling around the water hole until they started up the incline to the trees above just as Lynne turned on the engine and we began our way back to the Lodge.

We were the audience for a Story orchestrated on our behalf. Had the elephants decided to reveal their ability and desire to communicate to others beside Cyndie and myself?

Then came the moment we had been anticipating. The last minute of the last hour of the last day when we had always met the Ambassador. But we did not see a single elephant that day. It was greatly disappointing but not surprising as a much needed rain had been falling all day and the animals, particularly the elephants, do not come to the river when it rains. Still, it felt as if the entire trip to Africa had been for nothing.

But as we were driving away, Matt reminded me that he had suggested that I change my watch. “Yes, Matt, you told me my watch was wrong and I moved it ahead to coordinate with yours.”

“Look behind us,” he said. Cyndie and I turned around. There, at the Chipungo tree, was a large bull elephant. Without the adjustment, it was 6 pm. The Ambassador had arrived. I was stunned.

We had left early and missed our appointment because Matt, our guide, had advised a time correction. And it was Matt who saw the Ambassador at our meeting place at the agreed- upon time. Cyndie and I were already convinced of the real if inexplicable connection with the Ambassador. But Matt, a ranger, would need his own irrefutable proof. He got it. Once again, an elephant had created a narrative that was incontrovertible, even by a skeptical guide.

Next we wanted to see if other elephants would contact us outside of Chobe. Mashatu, one of the largest privately owned game reserves in southern Africa, is sanctuary to the largest herds of elephant on privately owned land on the continent. We were the only guests except for the President of Botswana and his retinue. The two guides who accompanied Cyndie, Matt and myself were seasoned rangers, who had been partnering for many, many years. We knew the quality of the men we were with when we were driving back after sunset and the tracker spotted a newborn hyena in a hole behind trees and brush more than 30 yards away.

At Mashatu, we were able to create our own routine. Introduced to the animals and terrain in the early morning hours, we spent the afternoons among the elephants. We were particularly interested in whether the elephants would respond to us differently than they do to the other tourists who gathered from other lodges. From the beginning, it seemed that the Mashatu elephants found us interesting, particularly the little ones who often came very close, not always to the mother’s liking.

Early on, a very young bull came to the side of the car and put his trunk up to Cyndie and almost touched her, another one examined the front of the car and another the rear. Each day, the elephants permitted us to observe the activities of the herds as if we were being introduced to their culture, the complexities of their relationships and, particularly, their appetite for play.

On our last day, we drove down a sand river and were met by Henry, a bull elephant whom Eric, the guide, had seen born fourteen years earlier. A gentle elephant, he allowed Eric to park the truck next to him under the tree. Such a greeting, like all the other encounters, appeared both purposive and happenstance. In ways we had not experienced ever before, we found ourselves amidst dozens of elephants engaged in every possible elephant activity. An older bull and a younger one were tousling – the younger one being chastened.

Little ones were frolicking, one pushed down into the mud, a pod gathering around it. Older ones were above on the ridge, eating. When they passed us they came closer and closer, making eye contact. Sometimes they lined up in a semi-circle, staring. We were not peripheral. We were somehow incorporated into the herd, their ways openly and deliberately displayed, including what the guides had never seen before, a female nursing two babies. What distinguished this moment from those in the past was that the elephants were not only allowing us to look at them, they were looking at us. “They are interested in you,” Eric said, puzzled.

Then it was the last hour of the last day we would spend at Mashatu. Our plane would be leaving that afternoon. We were awed by having been received so openly. We couldn’t, however, leave without the last ritual of finding a place away from the usual animal trails, without visible snakes, animals, predators, to enjoy a stretch, a pee, and a late morning cup of coffee and pastry, outside the truck. Lounging around, relaxed and joyful, we saw elephants climbing up the hill toward us from every possible direction. They came in waves so close that we had to re-enter the truck in order to watch the procession; the entire herd, more than a hundred elephants, had come to say good-bye.

* * *

We spent the several days in Damaraland, our last stop, holding the range of questions that had developed over sixteen years of observation and concern, knowing that any answers would not address the greater mystery we were in, the magic of communicating heart- to- heart across species. Mornings we spent on regular safaris and sought the elephants in the afternoons when they would likely be at the river until sunset.

But desert elephants are different; they have adjusted to planetary difficulties. They can go one or two days without drinking, unlike forest elephants who must drink their fill twice a day. Some small herds of desert elephants are tusk-less, having genetically adapted in a very short time to poaching. Not having the means to protect themselves, these testy and somewhat hostile elephants have hidden themselves in remote and forbidding areas.

So I did not have high expectations. It seemed unlikely they would welcome close human presences. Additionally, we learned that our guide, Chris, was afraid of elephants. As a young boy, he had witnessed an elephant stalking a man who had undoubtedly done him harm. The man ran to the church for protection. When he felt safe, he ran out toward the nearby school, but the elephant, who had been waiting for him, scooped him up on his tusks and killed him. Elephants remember those who do them harm. Do they only remember individuals or the species?

I wondered on the last day whether the young bull elephant who slammed his tusks down on the hood of the truck knew Chris’ story or his fear. But Chris did not start the truck to retreat. Because relationships with animals are silent, they must be transparent and so are intrinsically truthful. One cannot deceive an animal; she or he is always reading your heart. And so the little elephant read our souls’ intentions and went on. Despite my concerns, the elephants allowed us near them and often exhibited curiosity about who we were. We went closer to them than the other tourists and stayed a long time, listening and present; this, we believed, encouraged a bond between us.

Photo by Cynthia Travis

Photo by Cynthia Travis

* * *

At the last hour of the last day a pregnant female approached us. She stood at the hood of the car, occasionally sweeping her trunk over the dust, looking at me for a long time, twenty minutes perhaps.

“Are you talking with her?” Chris asked.

“I am,” I answered, “but I don’t know if she is answering.” I was asking her to guide us as members of the Radical Elephant Movement. I was asking her to help us save the elephants from extinction. I was praying that she would imprint us so we would know how to stop the mad behavior of our species. But she didn’t answer. No words or thoughts appeared in my mind other than my longing to be of service for the restoration of the natural world.

Then, as suddenly as the Ambassador had turned away from us originally, she bolted for the hill above us as if there had never been a connection.

Perhaps we hadn’t gone to Africa for answers; perhaps we had gone to refine the questions we’ve been carrying for years, that have deepened and expanded with each encounter. Who has agency, the human or the elephant? The Ambassador, an individual, particularly gifted elephant? The herd? The elephant people? A unique aggregation of individual souls? The embodied Elephant culture? Increasingly, it seems that elephants by their unique immersion in a continuously responsive herd are exercising agency in relationship to us. Maybe they developed this capacity in response to the terrible circumstances of their lives as they face loss of habitat, interrupted migration corridors, poaching. all equaling extinction at our hands.

We are left with the original unfathomable events. How do the Ambassador and his people know we are coming to Chobe? It may be that elephants, who are probably more intelligent than we are through their capacity for unparalleled empathy, can read the heart across vast distances, unimpeded by species barriers, and send out subliminal communications which I / we receive and respond to by coming to meet them.

I was reading The Elephant Whisperer by Lawrence Anthony when flying home from my 2011 visit to Chobe. Anthony, the founder of the South African reserve Thula Thula, had had a remarkable relationship with elephants based on intimacy and proximity. One might even say the elephants engineered their transfer to his reserve in order to create this relationship. I wanted very much to meet him but he died suddenly before I returned to Africa. Then stories emerged of the elephants knowing of his death and coming to his house every year on the anniversary of his death. How is this possible? What does it mean? What do the elephants want us to know?

Cyndie and I will be returning to the elephants in the last days of December 2016. We will spend New Years Eve and another few days at Thula Thula. Perhaps Anthony’s herd will visit us.

In the last years, we have been allowed to be very close to the elephants. But this connection has not yielded the answer to the essential questions: How and why are they communicating with us? What do they want? How can we meet their call? Perhaps in Thula Thula we will be able to be immersed in the herd. Perhaps they will speak to us. Or, perhaps this time we will understand. I am praying that the elephants will take us across another barrier. I am hoping we will hear and listen deeply enough to yield entirely to elephant intelligence, to allow the elephants to guide and determine the future actions of the Radical Elephant Movement.

* * *

Mandlovu Mind – music by Jami Sieber, poem by Deena Metzger

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OSQGVWmt1V8

MANDLOVU*

Suddenly, I am of a single mind extended

Across an unknown geography,

And imprinted, as if by a river, on the moment.

A mind held in unison by a large gray tribe

Meandering in reverent concert

among trees, feasting on leaves.

One great eye reflecting blue

From the turn inward

Toward the hidden sky that, again,

Like an underground stream

Continuously nourishes

What will appear after the dawn

Bleaches away the mystery in which we rock

Through the endless green dark.

I am drawn forward by the lattice,

By a concordance of light and intelligence

Constituted from the unceasing and consonant

Hum of cows and the inaudible bellow of bulls,

A web thrumming and gliding

Along the pathways we remember

Miles later or ages past.

I am, we are,

Who can distinguish us?

A gathering of souls, hulking and muddied,

Large enough – if there is a purpose –

To carry the accumulated joy of centuries

Walking thus within each other’s

Particular knowing and delight.

This is our grace: To be a note

In the exact chord that animates creation,

The dissolve of all the rivers

That are both place and moment,

An ocean of mind moving

Forward and back,

Outside of any motion

Contained within it.

This is particle and wave. How simple.

The merest conversation between us

Becoming the essential drone

Into which we gladly disappear.

A common music, a singular heavy tread,

Ceaselessly carving a path,

For the waters tumbling invisibly

Beneath.

I have always wanted to be with them, with you, so.

I have always wanted to be with them

With you,

So.

*Mandlovu is the word the Ndebele people of Zimbabwe use for female elephant. It is connected in resonance with Mambo Kadze the name for the deity that is both elephant, the Virgin Mary and the Great Mother.

Deena Metzger has been writing for fifty years. Story is her medicine. She is the author of many books, including most recently, the novels La Negra y Blanca (2012 PEN Oakland Josephine Miles Award for Excellence in Literature), Feral; Ruin and Beauty: New and Selected Poems; Doors: A fiction for Jazz Horn; Entering the Ghost River: Meditations on the Theory and Practice of Healing. She has just completed a first draft of a new novel, A Rain of Night Birds. The novel bears witness: climate change arises from the same colonial mind that enacted genocide on the Native people of this county. www.DeenaMetzger.net

Want to comment on any Issue of Dark Matter, fill out the form here.

Copyright © 2014-2021 Dark Matter: Women Witnessing - All rights reserved to individual authors and artists.

Email: Editor@DarkMatterWomenWitnessing.com

Please report any problems with this site to webmaven@DarkMatterWomenWitnessing.com