November 2014, Issue #1

Seeing in the Dark

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Editorial

I. Living By Dream

Miriam Greenspan

Dreamkeeper

Seeing in the Dark

Seeing in the Dark

Deena Metzger

Living By Dream

Susan Bradley

Dream Dogs 1 and 2

Patricia Reis

Over the Edge

Cynthia Travis

Accounts

Maia

Naming

Sara Wright

Angels: After the Maine Bear Referendum

Marilyn DuHamel

Call and Response with An Irish Brogue

Susan Cerulean

Holding Sacred Posture

Kristin Flyntz

Grieving with the Elephants

II. Towards a Resurrected

Knowing

Sonja Swift

Good Morning, (End of the) World: Notes toward a Resurrected Knowing

Jan Clausen

Veiled Spill #11, #12, #13

Cynthia Travis

The Original World

Maia

Letter from Demeter

Susan Bradley

Honeycombed

Hexagons with Packets

Hexagons with Packets

Kate Miller

Bearing the News: Wolf Hunt Revived in Minnesota

Sharon Rodgers Simone

A Parliament of Ravens

Marilyn DuHamel

Broken Open

Margo Berdeshevsky

Door

In the Falling of Late Fire Days

In the Falling of Late Fire Days

And Our Hands

And Our Hands

L’Amour n’est pas mort

L’Amour n’est pas mort

Sara Wright

My Yellow Spotted Lady

Regina O’Melveny

Corydalidae cornutus

Dyana Basist

What the Aspen Revealed

Harriet Ellenberger

Desire Spoken under a Night Sky

Moe Clark

nitâhkôtan

Sonja Swift

Good Morning, (End of the) World:

Notes toward a Resurrected Knowing

02.01.14

I am out hiking on black lava rocks, heading toward a butte overlooking an even larger peak. En route I talk with a person who tells me that because of all the strange and drastic changes humans are making to the world the volcanoes themselves are holding back their usual flow. But--this person told me--eventually they will release hot magma in giant bursts as if in response, as if to cleanse the world.

1.

This is the voice of one young woman trying to listen, learn and remember during a time of much destroying and forgetting.

2.

When did people stop living lives guided by beauty? When and why did people stop listening to the earth? How do we again learn to listen?

For however obvious it may seem that gobbling up the earth will leave us high and dry, people continue to do so, absentmindedly, and with apparent disregard for the continuum of life.

3.

—Our senses evolved in relationship with the natural world and in contact with other beings, species, and animals—

This, I find noteworthy.

4.

My own sense of place is born of close proximity to rangelands and oak groves, red-tailed hawks and coyotes; the scent of sage smeared into my forehead. I grew up on a California ranch where we raised Texas longhorn and grew subtropical fruit. Chumash country. Bordered by neighboring ranches in all directions, lands that were parceled off centuries ago when the hungry Spaniards killed off the grizzlies to feed their expanding missions. I found the spaciousness around me comforting.

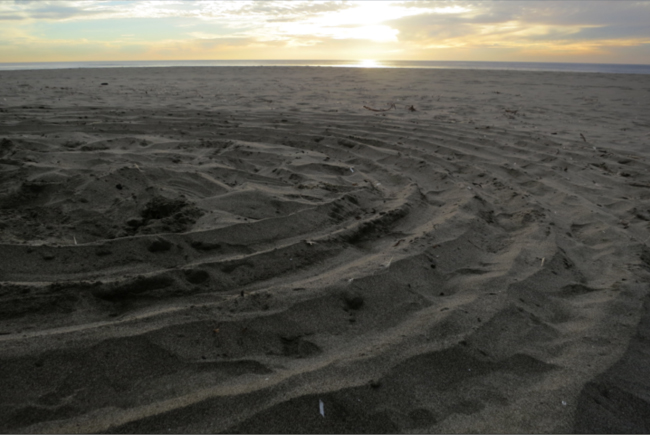

The sunburnt summer thatch I grew up with, that in times of drought makes California grasslands look especially like sand dunes, is a direct result of the Spaniards and Portuguese thinking California was Spain or Portugal and treating the land accordingly: overgrazing on hills that weren’t accustomed to horse hooves and cattle, replacing perennial species with annuals, and dismissing fire as a tool for tending landscape.

All that aside, my heart belongs to the gnarled live oak trees and worn-down rangelands of California because that’s where I’m from. It is as much a part of me as the color of my eyes. This original relation to landscape has given me something worthy of defending, as idea, as vision, as guide.

5.

There is a nuclear power plant appropriately named El Diablo that is situated some 30 miles as the crow flies from our family ranch. California is known for its earthquakes, and a fault has been located only a few miles off the coast from where radioactive waste is stored in yawning pits. A few years back I got up at a community meeting called to discuss prolonging the operations of this plant and said:

I live up Clark Canyon. I was born and raised there. It is my home. And, you know, we’ve got a siren that PG&E tacked up to one of the power lines that run through our valley. It hangs there, blank white, a stark reminder. Should that siren ever start blaring it means one thing: that we’ve got to run like hell and never come back.

6.

We are the same stuff the cosmos is made of. The same laws that form planets form us. Our bodies, like the earth, are made of stardust formed in highly volatile, exceedingly hot, exploding stars.

To remember that everything we are made of was made in the core of a star during a very hot explosion is to reckon that we share something quite intrinsic with every winged, hoofed, leafed, spiraled, webbed, finned, gnarled, creature and being on this living earth.

7.

Anaviapik, an Inuit elder, visits London for his first time to help edit a film about his people. Upon driving through the busy, heavily-trafficked streets his first day there, surrounded by asphalt, brick buildings, steel and concrete, with cabbies honking, watching people zip by, their attention glued to the roadway ahead of them, he breaks the silence by saying: Now I understand why the Qallunaat [white people] come to our land to get the oil.1

8.

Pave the land, demolish the land, desecrate and poison the land, and perception is plundered, as well.

9.

There is a mockery of life going on these days in an era where the dominant paradigm is industrial development at any cost. Where profit rules, where decisions are short-term, where people spend their frenzied lives keeping pace with technology, with industry, with fighting the wreckage wanton industry causes.

It has never before been so common to stare into the void of computer screens all day long, or to have to no clue as to where your food comes from. Bombs are a relatively new invention. They came about around the same time the prairie got plowed under. Genetically modified crops were developed a mere 30 years ago by the same businesses involved in chemical warfare. Farmed salmon, another recent calamity, spreads viruses to wild salmon populations that turn their strong hearts, evolutionarily equipped for a journey from ocean to river headwaters, into mush.

10.

Susan Griffin writes: Slowly, year after year, decade by decade, we grow used to the unspeakable.2

Grin and bear it, some say.

We’ve adapted in a detrimental sort of way. What we call normal—poisoning fresh water to extract more crude oil or uranium or gold because it makes money on the stock market—is socially accepted mental illness.

11.

I am trying to resurrect a knowing, soft and gentle, unquestioned, that’s always been, a knowing born of survival and enchanted by life.

12.

Some years ago I found myself moving from California to Dakota. I’d met a man, a Dakotan, who invited me to the Black Hills, South Dakota. I needed refuge at the time and he offered me a place to rest, a place to gain perspective. I didn’t come bridled with expectations; I arrived a castaway with love eyes. The Black Hills reminded me of the land where I grew up. And the Great Plains, stretching toward all the points on a compass, reminded me of the Pacific Ocean. Dakota, I would learn, is the center. You can go east or west, north or south. You can go all directions and you are at the same time far, far away.

13.

To defend original relation to landscape is to defend being in the here-and-now, which is really our true inheritance as humans alive on this magnificent planet. People who aren’t bonded in this way have a hard time with the people who are. Women weren’t the only ones killed for collecting herbs from the forest and praying for the earth. Men got burned alive as well. In Iceland the majority of people executed for witchcraft were male. Women were drowned, while men were burned.3

People who make peace with the unknown, who honor the great mystery, who know they are bodies born of planet earth, born with the aptitude for complex, coherent, sometimes inexplicably intuitive intelligence, have been and continue to be undermined if not outright killed for lovingly refusing to control the untamable and to desecrate the places they call home.

14.

The Dakotas feel like another version of ocean to me. Prairie Ocean. Great Plains Ocean, where the winds can be as harsh as oceanic gales, and driving through a blizzard means you risk being capsized in a ditch if you time it wrong. It is a place that pushes you to your edges. It’s like being in the salt-water ocean, only the swell and waves are stationary. In the winter, when the polar front descends from the high north, snow forms into glistening breakers along the ditches on the side of the highways. When I’m driving in big sky country, I am reminded that we are, as a matter of fact, crossing the bottom of an ancient sea. The sky itself is its own ocean, storming, and we’re on the sea floor looking up.

To connect California to Dakota is to connect Pacific sea foam to windswept plains. Dusty rainbow of prairie. Thunder like freight trains. Sunburnt hillsides. Fog thick as blankets. It is a spiritual traverse from the edge to the heart. Every journey I’ve made across the western reaches of this country has become an act of weaving, retracing, and paying my respects.

15.

I harbor a deep need for spaciousness: big-sky spaciousness, and the freedom that comes with roaming through places that test the limits of the mind. The need to feel free is innate. Free as in cyclical time not alarm clocks. Free as in living in the here and now.

16.

Isak Dinesen bore witness to the kind of staggering change that colonization brought to the African continent, changes that have in many ways become almost daily events the world over.

To the south-east, a long way off, the plains of the farm where in years of drought we had fought the wild, gluttonous grass-fires, and the squatters’ plots, with the pigeons cooing high about the chattering and the sounds of cooking below, were being cut up into residential plots for Nairobi business people, and the lawns, across which I had seen the zebras galloping, were laid out into tennis courts. These things were what are called facts, but were difficult to retain.4

When changes like this are turned into numbers and facts, dissociated and made abstract, then people permit them. When people don’t know what’s been lost, they don’t know what the world used to look like. When they can at least imagine it, then they are more likely to endeavor to preserve what’s left.

If I didn’t grow up roaming among oak groves and herding longhorns, and later spend long and solitary afternoons trailing through short-grass prairie keeping company with bison, I might not care as much as I do about the return of the buffalo or perennial grasses or healthy rangelands. I might not pause to imagine California when it was relatively green year round, when the Anza-Borrego Desert had marshes and wetlands, or what the prairie looked like when it was home to grizzly bears and sixty million bison.

17.

In a sound and healthful society, there wouldn’t be communities swallowed up by the Alberta tar sands who can’t eat their own berries, fish, or caribou anymore and so have to ship in blueberries from New Zealand or Chile or Vermont. There wouldn’t be continued razing of the Amazon for soy and palm oil plantations. There wouldn’t be the petro state known as the Bakken that has lit up the sleepy grain fields of northwestern North Dakota with gas flares as numerous and bright as a veritable city skyline. Early satellite photos of the oil boom left people musing they’d found a new city that had suddenly cropped up out of nowhere in the center of the continent.

I remember one night in the dead of winter arriving in Williston, North Dakota off the train to visit my partner’s family for Christmas. As we neared, we saw a demon’s landscape, flares glowing orange against a pitch-black night sky, a land overthrown; blood of the earth burning.

There are still petrified redwood stumps in North Dakota from the age of the dinosaurs.

18.

This is how giving-a-damn-about-it-all can feel sometimes:

Cell phone rings, 7:30am on a Sunday morning. I pick it up off the floor and toss it to my partner.

He looks at the number, “Oil field worker, they’ve got the wrong number again.” Setting the phone on the window ledge he slumps back against a pillow. It’s too early to get flustered. Too early to count how many times this has happened before. It is too damn early on a leisurely Sunday morn to get yet another call from one of the innumerable hordes of men flooding in from every state in the nation to make some fat cash in them god-forsaken North Dakota badlands, nothing but grass-and-wind, flat-and-empty, we’re-here-now-and-we’re-drilling-fast-and-furious-for-all-its-god-damn-worth!

Beep. Call ended. A moment passes and the message alert sounds with a twang. He listens drearily. “Who was it, what’d they say?” I inquire.

He mimics the message left by the nameless voice at the end of the line, “Yeah hey, uh, Joe. There’s an oilrig, uh, billowing black smoke down to the left of the highway. Maybe you could go and check it out? All right, yeah, well, later then.” He shakes his head and furrows his brow, “The guy doesn’t even listen to the message machine, my name isn’t Joe. Seven fucking thirty on a Sunday morning and they’re working, always working. They just don’t stop. Looking out on land that isn’t theirs, land they don’t give a damn about.”

He sighs. I sigh, thinking to myself at least the bloke’s not drunk and redialing the same wrong number five times over to talk to Chad or Sylvia. That’s happened a time or two. Relentless.

Good morning sun. Good morning new day. Good morning (end of the) world.

19.

In the introduction to her book of poems Appalachian Elegy, bell hooks writes about her kinfolk, the renegades and rebels who want to live free, and the steadfast belief in remaining self-determining people. She writes about freedom in the same breath as she writes about the outdoors, backwoods in rural Appalachia, and it reminds me how these things—freedom and roaming beneath an open sky—are synonymous.5

20.

Even amidst the onslaught there is space in the Dakotas and the wider West. Even with the North Dakota oil boom and fifteen-foot-high flares wasting all the natural gas for quicker oil export, the Wyoming coalfields, one of which, the Black Thunder Mine, takes the cake for being largest in the world, the resumed threat to mine for uranium in the Black Hills after a tireless fight thirty years ago, and all the coastal retirees plopping glitzy ranchettes down on forty-acre parcels—even with the extractive industry blasphemy and misplaced suburban aesthetic—there is still big sky and big wide-openness.

There is still room enough to feel free.

21.

I walk in quiet company with seedlings and stoic tree trunks. Deer tracks beside paw prints in moist, savory, brown mud. The nurturing sound of water trickling, descending from the grey steel of a culvert pipe onto black rock and emerald moss; the lushness of a wet forest. The winds whisper through the tree tops, accentuating forest scent, the way when an oven cracks open the aroma of freshly baked bread wafts skyward. Sunlight patterns the veins of leaves, splashing shadows about like a painter flinging ink across a canvas.

Why is it that I can feel in more intimate, affectionate company among leaf litter, pine needle, snail, and shadow than surrounded by the multitudes that blaze through city streets daily? And yet I have also met passing strangers’ eyes in least expected moments, seen them twinkle and greet me in momentary presence, and been reminded again and again that we are all one despite industrial frenzy and the relentless cementing of the soil.

It is the bigness, though, that is so palpable in the forest groves, desert lands, and outback regions I go to for solace and space. A bigness beyond my own small frame. A bigness that I know, indisputably, I am a part of.

Sunlight pours through drifting clouds like soft breath. Pine needles fall one by one from the wind-swept upper branches like tail feathers. There is an alikeness to everything, made as we are of dusty ancient memory. I sit cross-legged in amber-colored pine needles, among pinecones and broken sticks, in a puddle of sun. To know the earth can contain my lonely human suffering and match my deepest swell of joy is one of the greatest gifts of all.

I reach a clearing. An owl hoots. A raven caws. I smile for the pure pleasure of being alive. Water-blue sky brimming overhead; wind in contact with grass and leaf, rippled by each gust. I walk to the edge of shadow meeting sunlight as if it were the shoreline to another world.

22.

All land is sacred, I told someone once. They disagreed. Told me some places are less important.

Sure, there are sacred sites, I said, powerful places like acupressure points across the globe. Places where people have long gone for prayer, where hunting is not allowed, places to journey to for a vision. But all land is sacred. The second you think otherwise, justification is possible, and sacrifice zones. “Extractive industry” doesn’t sound all that bad in a “barren desert” or on the “flat plains.” The less-than-sacred-places are where we test nukes, turn mountains to rubble, and leech radioactive waste into aquifers below.

I was thinking about North Dakota that day. And a few days later I was driving through Nevada.

North Dakota, where prairie was plowed under, where bison herds were slaughtered for their tongues, for show, their bones ground up and later used for ammo, where nuclear bomb silos were gutted into the soil beneath farmsteads in preparation for war. Nevada, where the first a-bomb spewed its mushroom cloud and men sat by placidly ignorant of the direct association between the black magic of atomic ammo and the toxic residue of debris on their skin. Places dismissed for their vastness.

“Vast” becomes “wasteland” in the eye of the taker: a better word for justification. A hang-on from the days of conquest when men sought to “penetrate the unknown,” calling wilderness “uninhabitable,” and creating the notion of lands “unpeopled” by killing those who dwelled there and then saying they never existed. To perceive the ocean, prairie, desert or tundra as vast is to stand in awe; to view it as a wasteland it to lay the grounds for thievery.

23.

It matters where people pray for the earth to keep rotating and the sun to keep shining. These places are precise and returned to again and again. It matters where you are born and where you die. It matters what landscape you first entrained to as a child.

The real question is how are people not connected to place, to earth, to our shared existence? How are people today not aware of the whole planet as a living organism? How can people not be aware of the great mystery when this is it; we are on a verdant planet circling a blazing sun?

24.

I’ve heard it said that it’s the prairie dogs that sing for the rain. When they are standing on their hind legs with their tiny paws pressed together in sun salutation it is hard not to mistake their stance for prayer. I was out walking through Wind Cave National Park in the Black Hills one afternoon when I came to the edge of a prairie dog town. They started hollering in that high-pitched way they do, calling to each other, messenger calls, warnings. I sat down in the patch of shade beneath a ponderosa on the hill slope leading to their village and I began to sing. In moments they quieted down, and then silenced. I stopped singing and we all sat there in silent company.

25.

There are things that I long for. Bison in the millions, the drumbeat of their hooves, the accompanying dust clouds reminiscent of stars birthing. Black night sky undisturbed by jet planes and city lights and gas flares. Perennial grasses that stay green through the heat of summer. Syllables of languages forgotten, gone with the murdered, with the old woman who had no one else to speak with.

I have often wondered if we, the human community, are in the darkness we are in to try and comprehend something, something devastating, so we never again repeat it. It is easier to understand others’ turmoil when one has known the likes of it firsthand. Healers require this perspective. Which is why the shamans have always tended to be the wounded ones, the seers on the outskirts of the village. Wounding gives way to vision. And yet wounding only gives way to vision when you let the light shine in.

Either we are at the beginning of the beginning or nearing the end. There is no telling. There is just each one of us, and our sacred sense of wonder and awe.

26.

Alice Walker writes:

I know perfectly well that we may all die, and relatively soon, in a global holocaust, which was first imprinted, probably against their wishes, on the hearts of the scientist fathers of the atomic bomb, no doubt deeply wounded and frightened human beings; but I also know we have the power, as all the Earth’s people do, to conjure up the healing rain imprinted on Black Elk’s heart. Our death is in our hands.But what I’m sharing with you is this thought: The Universe responds. What you ask of it, it gives. The military-industrial complex and its leaders and scientists have shown more faith in this reality than have those of us who do not believe in war and who want peace. They have asked the Earth for all its deadlier substances. They have been confident in their faith in hatred and war. The Universe ever responsive, the Earth ever giving, has opened itself fully to their desires.

6

To be alive is to have responsibility for what follows in our wake. It is a chance to perceive the dynamic interrelatedness of life, experience beauty, and celebrate the greater mystery of our being here at all, from stardust to birth and back again to dust. We each take part in this self-creating universe through our every thought and action. We are home on this earth. We are creative beings. And we can heal. To remember these things is to step off the runaway train and go walking, it is to stride bravely toward a future that celebrates rather than destroys the continuity of life that we ourselves are part of.

We are indeed the world. Only if we have reason to fear what is in our own hearts need we fear for the planet. Teach yourself peace. Pass it on.7

27.

Are we drones or rainmakers? Are we asking the Earth for uranium or sweet water? Are we living in hatred or in love?

What comes after pillage?

28.

We drive behind a long-load hauling freshly tapped crude oil or contaminated waste water, I’m not sure which. We drive through the rain pattering fresh-water droplets, while the windshield wipers smear bug-guts and fog over our forward view. We drive past barreling semis and homesick truckers working the way ants work, unremittingly. We drive past a 10 commandments billboard and remark how it would be worth adding to the line-up: Thou shall not question thy CEO. Or perhaps: Thou shall not hinder gluttonous industrial development at any cost. We joke. Coarse jokes. Hard truths. With 15-foot high gas flares, we are stating the obvious. We drive through memories of old grief over the seemingly blunt-inevitable. They knew the oil was here. They waited thirsty until Dick Cheney made fracking fluid exempt from the Clean Water Act. Clever move, old man.

And yet there is an impermanence to the extractive industry blasphemy ongoing in all corners of the world, whether North Dakota oil fields or gold mining in the belly of the Amazon, all such last-ditch efforts to gobble up what remains of intact landscapes and undermine cultural know-how, narrative, language and community. There will come a day when the wells dry up and the tractors rust in mud-slicked red-earth ravines, and silence softens in the wake of debauchery.

I’ve expended a lot of energy cursing the insane fool in slacks, coat and tie, wearing a shit-eating grin on his face, the ravenous thief, when the thief is an industry buffered by minions of young jobless men and stockholders who don’t ask what’s behind the numbers on their balance sheets.

I’ve cursed and cried and gritted my teeth. I’ve done what I can within my power to be a kind citizen of the world. I write. I bear witness with honest eyes. I peer into the cavernous tunnels they dig and see the future flaming, and I question why? What for? Why such furiousness and insatiability? And you know, I see unloved children. I see infants’ yearnings in the eyes of hungry men.

These are heartsick times. These are exiled times. This experience is happening to many of us whether we like it or not.

Raindrops lick my passenger window, carrying the memory of how water has been polluted and also revered. The people who pray to the rivers and the lakes, to the oceans and springs, they are still out there singing. I know it, because I am one of them.

Sonja Swift writes toward a place of understanding, both of herself and of our world. She has a masters from Goddard College’s IMA program, with a focus on place-based creative writing and embodiment studies. She currently lives in San Francisco, California.

Sonja Swift writes toward a place of understanding, both of herself and of our world. She has a masters from Goddard College’s IMA program, with a focus on place-based creative writing and embodiment studies. She currently lives in San Francisco, California.

Want to comment on any Issue of Dark Matter, fill out the form here.

Copyright © 2014-2021 Dark Matter: Women Witnessing - All rights reserved to individual authors and artists.

Email: Editor@DarkMatterWomenWitnessing.com

Please report any problems with this site to webmaven@DarkMatterWomenWitnessing.com