April 2015, Issue #2

FRAGILE ONGOING

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Editorial

I. OPENING REMARKS

Jan Clausen

“This Moment the World Continues”: Writing under the Sign of Species Suicide

Robin W. Kimmerer

When Earth Becomes an ‘It’

Kathleen Dean Moore

The Rules of Rivers

II. GRIEVING

Cynthia Travis

The Music of Grief

Megan Hollingsworth

Pacific

Ruth Wallen

Cascading Memorials: Public Places to Mourn

Joan Kresich

Letter to a Yellowstone Wolf

Susan Marsh

Elegy for the Cranes

The Hunters

The Hunters

Karla Linn Merrifield

William Bartram Triptych

Dana Anastasia

trinkets

Gillian Goslinga

To Witness

III. GUIDED

Deena Metzger

Dreaming Another Language: She Will Not Kill

Alexandra Merrill

Homage to Bees

Sheila Murray

Infiltration

Prey

Prey

Judy Grahn

Dragonfly Dances

Laura D. Bellmay

A Call from the Edge

Carolyn Brigit Flynn

Grandmother Squirrel

Nora Jamieson

Fleshing the Hide

Sara Wright

Cardinals at the Crossroads

Valerie Wolf

Dreaming the Future

Ruth Wallen

Cascading Memorials: Public Places to Mourn

We used to get a lot of rattlesnakes. Now you don’t see rattlesnakes and you don’t see deer. You still get coyotes, and plenty of rabbits and squirrels.

I miss the frogs, too. Unless we get a pretty good rain that brings them all out, you don’t hear them at all.

The other thing we had years ago was horned toads. I haven’t seen one in years. I remember that my youngest boy had a horned toad in an aquarium. He hand fed it for six months with red ants and then let it go. When the development came, the red ants got overtaken by black Argentinean ants. —RS and HW

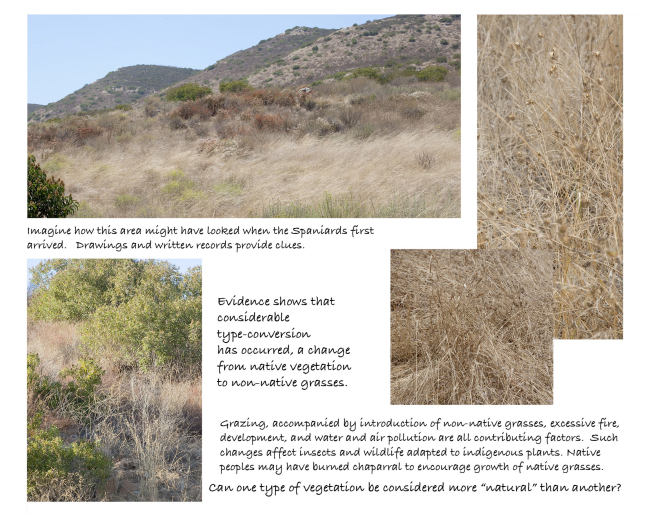

Carmel Mountain Chaparral in April 42”x16”

The statements shared above are from residents of Arroyo Sorrento, San Diego, a small enclave just north of the University of California, San Diego and east of the coastal community of Del Mar. This is the place I first visited upon moving to San Diego thirty years ago. I’ve been coming back here, and to the wild mesa pictured above, misleadingly called Carmel Mountain, ever since. I imagine that similar recollections could be elicited from many parts of the continent, although more readily here in southern California where the human population has grown so rapidly. A hundred years ago there were well under a hundred thousand people populating this large country. Now there are over 3.2 million.

We used to look all of the way to Black Mountain and just see coastal sage. East of Del Mar, it was like a big national park. —TR

Such rapid change means that most adult residents moved to San Diego from somewhere else. For each new arrival, what they find as they settle into their new home becomes their baseline. It is hard for newcomers to imagine that only ten or twenty years ago the local ecology was radically different. While the lack of collective historical memory may be more extreme in areas of the country with rapid growth, it is characteristic of our times as a whole, with frequent migration common throughout the continent.

Sketchbook page from Mission Trails Park Memorial, 9”x12”

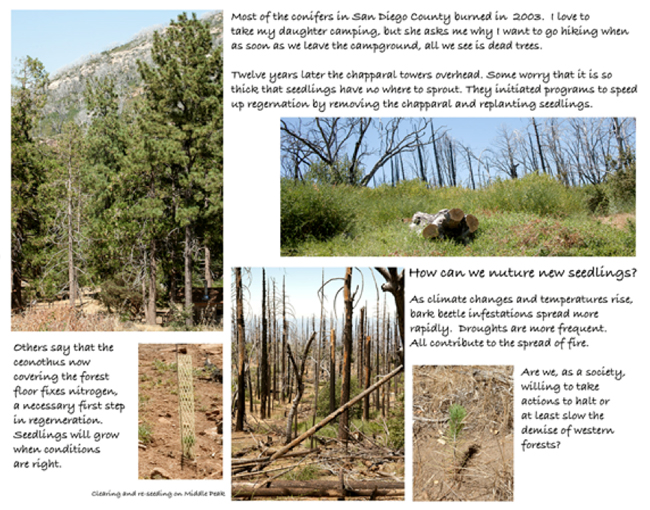

Even for those who have stayed in one place, the changes that have occurred in San Diego County just since the turn of the twenty-first century are hard to fathom. Fifteen percent of the land area of the county, primarily back country, burned in 2003, and another fifteen percent burned again in 2007, overlapping the earlier fire in some places. Most of the conifers in the high country burned. I can only hope that they grow back in my daughter’s lifetime.

Similar stories can be heard elsewhere. Wildfires, drought and bark beetles have ravaged western forests. Frogs are disappearing throughout the world; bats are dying by the tens of thousands. Whether one listens to the news from around the continent, or pays close attention to one place, the multiplicity of stories about environmental degradation are startling.

Middle Peak, Cuyamaca Forest, San Diego County, several years after 2003 fire, 24”x40”

Now is a time not only to pay close attention, to bear witness, to remember—but to grieve. Cascading Memorials is an ongoing project to provide spaces for public memory, places to share stories, and places to mourn. It began in my community as a gallery exhibition, then moved to exhibitions elsewhere, with plans for an interactive web site and outdoor public installations. The work calls viewers/participants to attentiveness and to appreciation and gratitude for their surroundings. It provides a space to share in the wisdom of scientists and fellow citizens, and to grieve the rapid loss of the environments in which we live.

Cascading Memorials: Urbanization and Climate Change in San Diego County, Athenaeum Music and Arts Library, San Diego 2012

I have begun to create memorials to specific places that are undergoing rapid change. I focus on specific sites so that I can get to know them intimately. I return to each place frequently to photograph. Instead of the heroic sublime so frequently invoked in landscape photography, which distances the viewer, I present a fragmented, layered perspective of dynamic systems undergoing unusually rapid change. Carefully stitching together photographs is for me an act of reverence, respect. I try to convey a sense of my gratitude, the wonder of the experience of being in a particular place. Accompanying the photomontages in gallery exhibitions, a single poetic question on the wall ignites viewers’ curiosity. Sketchbook pages allow for more detailed exploration, combining text, drawings and photographs to provide scientific and historical context, and raise further questions.

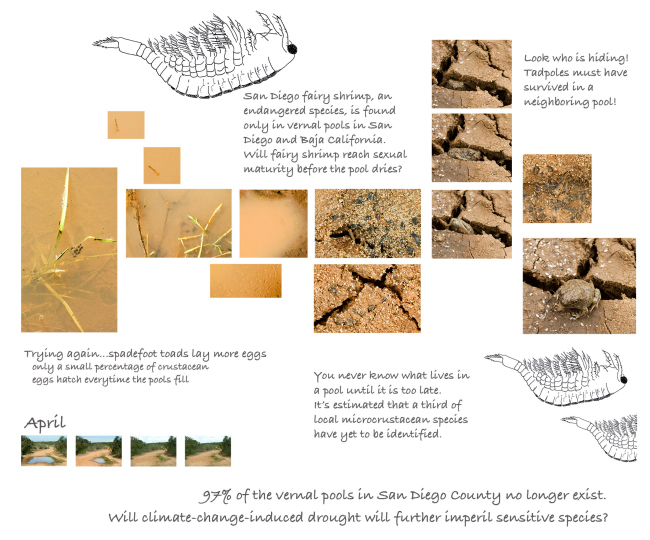

Continually returning to the same places provides the opportunity to look closely. It was only after years of walking on Carmel Mountain that I realized that the puddles along the path were actually vernal pools, ephemeral pools that are home to tadpoles, insect larvae and a host of invertebrates that live nowhere else. Ninety-seven percent of the vernal pools in San Diego have been destroyed by urban development. It is estimated that at least a third of the micro-crustacean species in California vernal pools have yet to be identified.

Sketchbook page from Carmel Mountain Memorial, 9” x 12”

When a truck drove through a vernal pool that my daughter and I visit frequently, destroying the contour of the pool and crushing the inhabitants, we were both outraged and heartbroken. As Aldo Leopold observes, “We can only grieve for what we know.”1 When we develop a relationship with a place, loss becomes palpable. Ecological degradation is no longer a myriad of statistics or abstract facts.

You knew that you were living in a place and you knew who your company was. There were no fences between the homes. Owls behind the house. Hawks in the sky. Deer. Coyotes howling. I still see so clearly the mama quail and all the little baby quail with their heads bobbing up and down. There were often many families of them.

--Helen Meyer Harrison

In every public installation of this project, I not only share memorials to sites with which I have an intimate connection, but I ask viewers/participants to share their stories of animals, plants and places they have loved that have disappeared or are changing irreparably. Aldo Leopold writes that the consequence of ecological awareness is living “alone in a world of wounds.”2 Collective sharing, not only of loss, but gratitude for the places that we have known and loved, breaks this isolation.

When I first visited the Dawson-Los Monos Canyon Reserve, long before I dreamed that I would become its manager, I used to drive across the agricultural fields to the south, and down a little canyon in the landscape to reach the main meadow of the reserve. Along the way I passed through an open valley with grand oaks and chaparral, as well as wet meadows and seeps, very different from the Los Monos Canyon just over the ridge to the north. When they started to bulldoze the area for commercial development (much of which stood empty for 15 or more years) I had to stop the car because the tears made it impossible to see to drive. I finally got out of the car and screamed and screamed and screamed…

--Isabelle Kay

Unfortunately, rituals for public mourning of any kind have been largely discontinued. Between 1880-1920, public mourning, including mourning clothes and accouterments, gradually vanished from view to the point that Philippe Aries declared that in “industrialized, urbanized and technologically advanced areas of the Western world...except for the death of statesmen, society has banished death.” What is lost when a society has the hubris to deny impermanence, attempting to banish death from public consciousness? Consider that in the Sutra of Buddha Teaching the Seven Daughters the Buddha says, “If one knows that what is born will end in death, then there will be love.3

It is not grief, but the fear of feeling, the absence of sadness or rage, which leads to paralysis, despair and psychic numbing. In a widely circulated op-ed piece in the Los Angeles Times, Richard Anderson asserts: “the alternative [to grieving] is a sorrow deeper still: the loss of meaning.”4 Judith Butler argues, “Without the capacity to mourn, we lose the keen sense of life we need in order to oppose violence.”5 That includes, I would add, the violence of ecological destruction.

When we avoid grief, according to Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands, we live in a state of suspended melancholia, where grief is internalized and objects of loss are fetishized. She contends that this process of displacement gives rise to “nature-nostalgia,” manifesting in such activities as ecotourism or even campaigns to preserve a particular species or wilderness area. Such practices, although well-meaning, reflect a mythic or idyllic view of a natural world separate from humanity. Nature becomes a commoditized fantasy. Environmental destruction becomes incorporated “into the ongoing workings of commodity capitalism.”6

Tecate Cypress in arroyo several years after fire, 15” x 56”

Instead of idealizing a mythic wild, can we dare to love the world in which we live? As we witness loss—whether family homes, childhood haunts, the croaking of frogs, or stately old oaks and pines—can we dare to feel the pain of loss? Public grieving is an essential step. In communal moments of grief, when the flow of life is temporarily halted, when the ache of losing that which was loved feels unbearable, hearts open. Sense perceptions are heightened. One is touched by the full poignancy of the living world. From these feelings compassion arises. In this heart-opening, the vital interconnectedness of the living world is palpable.

Hearing testimony as many bear witness prompts not only sadness and outrage, but also a desire for explanation, for autopsies. Any answer prompts more questions, and increasing awareness of the complexity of ecological systems. As such, each explanation leads to the reestablishment of the network of ecological connections. In this heightened sense of interconnectivity with those with whom we grieve, and with a wider sense of self integrally intertwined with the environments in which we live, we can find strength.

Sketchbook page from Cuyamaca Memorial, 9” x12”

Tears are cleansing. Grief allows us to see with new eyes, eyes that demand accountability, responsibility to make meaning or sense of the loss and take action. As Joanna Macy reframes this, we can understand “pain for the world as a call to adventure.”7

Working on this project, I have noticed that as we bear witness to the immensity of change in our communities, even long-term ecological transformations, such as climate change become less of an abstraction. Whether it is flooding or fire, deep freeze or searing heat and drought, increasingly many of us have stories to share.

It is fear of change, fear of grief, fear of the implications of grief that is immobilizing us, hardening our hearts. Let us face the dark, bear witness, and share our stories. Let us dare to imagine anew, recognizing that as in any relationship, if we love the environments in which we live, we must give back as well as take. Let the tears flow, let us howl in anguish and rage, and let us act.

Ruth Wallen is a multi-media artist and writer with training in environmental science whose work is dedicated to encouraging dialogue about ecological issues and social justice. She has had innumerable solo and group exhibitions as well as created several web sites and outdoor interactive “nature walks.” Her work is currently on display at the Exploratorium in San Francisco. She has published critical essays in journals such as Leonardo, Exposure, High Performance, The Communication Review, Tikkun, and Women's Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, as well as several anthologies. She is on the faculty of the MFA in Interdisciplinary Arts Program at Goddard College and was a Fulbright lecturer at the Autonomous University of Baja California, Tijuana.

Web site www.ruthwallen.net.

Want to comment on any Issue of Dark Matter, fill out the form here.

Copyright © 2014-2021 Dark Matter: Women Witnessing - All rights reserved to individual authors and artists.

Email: Editor@DarkMatterWomenWitnessing.com

Please report any problems with this site to webmaven@DarkMatterWomenWitnessing.com