“Anything we love can be saved.”

– Alice Walker

As a resident of Baltimore for the last twenty-five years, I have spent many days on the Chesapeake, usually in a sailboat. Like many Marylanders, I am acutely aware of the state of our great estuary and her many tributaries. The Report Card issued in late 2014 by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation gives the State of the Bay a D+, the same grade as in 2012. Hard-won improvements in water quality were offset by losses in other areas, the impression of no progress defying the dedication of thousands of people and millions of dollars.

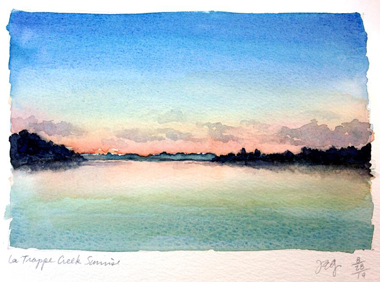

La Trappe Creek Sunrise – Julie Gabrielli

La Trappe Creek Sunrise – Julie GabrielliReturning from western Maryland on Interstate 70, I’ve seen a highway sign that says, “Entering Chesapeake Bay Watershed.” A colorful foursquare illustration depicts a wading heron, a blue crab, a rockfish, and water waves. The Chesapeake Bay Commission and state highway departments in Maryland and Virginia have scattered them on roadways throughout the watershed. This is likely counted as a win for awareness. The signs have subheads like, “Be a friend to the Chesapeake Bay,” “Please Treasure the Chesapeake,” and “Conserving Waterways Protects the Bay.” My heart aches at the irony of such a sign placed on a four-lane divided highway crashing through farmland and forest, where exhaust from cars and trucks spews nitrogen into the air and overheated, hydrocarbon-laden water gushes off paving into local streams. Scouring banks, this “runoff” erodes fragile soils and sends sediment into the Bay.

The Report Card says:

The State of the Chesapeake Bay is improving. Slowly, but improving. What we can control—pollution entering our waterways—is getting better. But, the Bay is far from saved. Our 2014 report confirms that the Chesapeake and its rivers and streams remain a system dangerously out of balance, a system in crisis. If we don’t keep making progress—even accelerate progress—we will continue to have polluted water, human health risks, and declining economic benefits—at huge societal costs. The good news is that we are on the right path. A Clean Water Blueprint is in place and working. All of us, including our elected officials, need to stay focused on the Blueprint, push harder, and keep moving forward…

Pushing harder is the mantra of the human-centered mindset that has been destroying the Bay since French and Spanish explorers came through in the 1500s, followed by Englishman Capt. Smith’s expeditions in 1607. It’s time to try something new. Or something ancient. In this uncharted territory of climate change, species extinction and the general breakdown of our old cultural stories, imagining new pathways is a first step towards taking them.

I have begun dreaming about going on a “Water Walk,” following the example of Grandmother Josephine Mandamin, who has circumnavigated the Great Lakes with blessing and prayer ceremonies and inspired many others to follow her lead. The shoreline of the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries presents quite a challenge, as it measures over 11,000 miles, longer than the entire west coast of the United States. Much of that is on private property or marshy and inaccessible. I’m intrigued with another possibility: walking the outline of the Bay watershed, an area of about 64,000 miles, in stages, as a pilgrimage.

Her surface is a threshold between visible and invisible worlds. Above: the great dome of sky, waves, wind, low-slung shoreline. Below in the brackish gradient from the Ocean: menhaden, crabs, oyster reefs, eels, skates, terrapin, mud. Above: cormorant, eagle, osprey, goose, great blue heron, ibis, pelican. Below: drowning, dredging, a riverbed gouged out by an asteroid, red algae, fossilized sharks’ teeth. Above: clouds, sunsets, gales, heat, dead calm, bluster, ice, moonrise, meteor showers. Below: eelgrass, shipwrecks, molting crabs, and sunken islands that once supported towns bustling with confectioners, baseball teams, Methodist churches and cemeteries.

Last summer, I had the helm of our old 34-foot Bristol as we glided slowly under a perfect blue sky, heading southwest on a broad reach out of Eastern Bay. We’d spent a quiet night anchored in Tilghman Creek off the Miles River, tuning ourselves to sunset, stars and sunrise. Poplar Island stretched along the horizon to the left and the wide-open Bay beckoned straight ahead. The breeze was light enough that I could divide my attention between steering and daydreaming over names on the nautical chart. The two-word epics read like Haiku: Hollicutts Noose, Wild Grounds, The Hole, Airplane Wreck. Gum Thickets. Brownies Hill. Bloody Point. What events had named those places? What ghosts lingered there? A waterman might board his skipjack and head out to Bugby Bar or Choptank Lumps or Devils Hole to tong for oysters early on a cold November day. The only data he needs to set course is the feel of the breeze on his nose and cheeks and the position of the sun emerging low on the horizon.

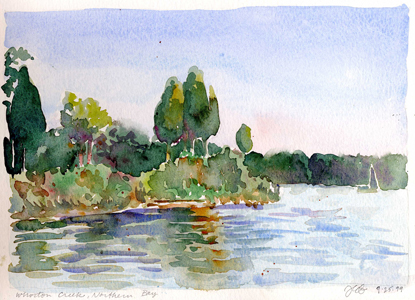

Wharton Creek, Northern Bay – Julie Gabrielli

Wharton Creek, Northern Bay – Julie GabrielliWhile the watermen were dredging and tonging oysters, fishing sturgeon and trout and netting crabs, the first oil in North America gushed forth from deep beneath the land far upstream in Pennsylvania. At that time, the Civil War raged through the land: men cutting each other down over stories of power and domination, economics and ownership. The land-dwelling men were soon beguiled by the energy from coal and oil, but the Bay’s watermen remained under sail well into the twentieth century. Eventually, even they could not compete with other vessels powered by the dark energy of the Underworld. Under pressure to continue feeding their families, one by one, they began retrofitting their boats, taking the heartbreaking step of cutting into wood-planked bulkheads to install loud, stinking engines.

“Civilization” spread like a crust over the land and suffocated the life out of it.

Despite their enslavement to coal and oil, the watermen still treasure their kinship with the Chesapeake herself. Skin of leather from hours under the merciless sun. Arms and backs sinewy from scraping for peelers in eelgrass. They speak of the wily Jimmy* with respect, as of a complex relation whose mysterious ways can be observed, sometimes anticipated, but never fully comprehended.

On the soft sandy bottom where the grasses wave in the tide, golden light filters down from the close surface. When the usually fierce Jimmy encounters a Sook half-hidden and ready to mate, he rises to the tips of his walking legs, dancing and waving his claws. She submits. He sidles up and embraces her tenderly from behind. In a cage made by his walking legs, she sheds her shell, becoming utterly defenseless and ripe for mating. Jimmy cradles and protects her, gently turning her to face him for the act. Their lovemaking lasts from five to twelve hours. Afterwards, they remain locked in a two-day embrace while her shell hardens.

I live near a stream called Western Run that feeds into a larger stream called the Jones Falls that flows into one of the Chesapeake’s rivers, called by the original people the Patapsco. I imagine the Bay offering this suggestion of a Water Walk to every heart living in the 64,000 square miles of her watershed. As I research the idea, it helps to see that I am not the first one who has said yes. Still, I have no idea what will be required of me.

In the Creator’s Original Instructions, women were to be the caretakers of the living water. When the big ships arrived in North America with men who did not know these instructions, many traditions were suppressed and forgotten. Some of the original people still follow the instructions and the prophecies of the Grand Chiefs, women like Grandmother Josephine Mandamin. She was born an Anishinaabe far to the north in a land carved by glaciers, and grew up on an island, living the same way as the Chesapeake’s first people—in kinship with the water, the fish, the birds, the sun and moon, and the seasons.

In answer to the cry for help from her watery home, which her people in their language called The Big Boss Lake, Grandmother Josephine took up her copper pail in 2003 and started to walk. She walked with her open heart along the awakening springtime shoreline, circling the entire lake to bless the water, to listen to and speak with the water spirits, to sing prayers of healing, and to perform ceremony by offering tobacco and thanksgiving. She walked to restore right relationship with the water and for the benefit of the next generations.

Crab Creek, Annapolis – Julie Gabrielli

Crab Creek, Annapolis – Julie GabrielliThe following year, she circled another of the Great Lakes, gathering attention and new participants along the way. These walks continue every year. Websites have sprung up, such as www.waterwalkersunited.com, www.idlenomore.ca, and www.nibiwalk.org. There’s even a Facebook group, Water Walkers United. Their journeys are both spiritual and physical. They walk to call attention to the sacredness of water, to honor and heal it, and to raise awareness of the need to take care of the water. Their 2015 Walk took place during July and August, trekking 846 miles westward from Ontario through Michigan to Wisconsin.

Many of Grandmother Josephine’s sisters have been inspired to organize Water Walks along ailing waterways in their own home places, including the St. Louis and Ohio Rivers. The 2014 Ohio River Walk spanned 906 miles from Pittsburgh to Cairo, Illinois. They walked for thirty-three days, averaging twenty-seven miles per day.

Closer to home, in May of 2015, walkers in Virginia trekked the three hundred and forty-mile length of one of the Chesapeake Bay’s tributaries. When the English came, they named this river the James, but it was also known as the Powhatan, after the great chief of that land. They walked to bless and pray for healing of the waters after a CSX train derailment in April 2014. The one hundred and five-car train, en route to Yorktown, Virginia from North Dakota’s Bakken shale region, spilled crude oil directly into the river, which then exploded into a fireball.

The Unity Walk began near the river’s source in the Blue Ridge Mountains at Iron Gate, Virginia. They averaged twenty-eight miles per day on the twelve-day journey, which took them past state parks, historic sites, farms, cities, wildlife refuges and industrial sites. When the group reached the Chesapeake Bay, they sang and performed ceremony to offer the headwaters from their copper pail. “We are telling the water, ‘This is how you began, and this is how we wish for you to be again,’” Ojibwe elder Sharon Day told a local newspaper. The walkers wept tears of joy to be greeted by a family of cavorting dolphins.

I imagine walking with a small group of companions, carrying a copper pail and pouches of tobacco and corn pollen. Walking with an open heart and listening, trusting that my sincerity will allow me to hear the song of the Chesapeake, even though in my growing up no one taught me how to do this. In my culture such things are dismissed as childish superstition. As I walk, my ancestors send visions of the great crust of my culture slipping off the living land, just as a crab sheds his shell. When my path takes me through the asphalt parking lot of an abandoned shopping center, I see the truth of their vision: knotweed rising to the light from a crack in the paving. The spirit of the knotweed plant sings of restoring balance to the waters of the human body. And my spirit is filled with hope. I know myself to be water, to be united by water with all other beings.

There are hundreds of thousands of creeks, streams and rivers in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. At the shoreline, the major tributaries are the Susquehanna, the Patapsco, the Patuxent, the Potomac, the Rappahannock, the York, the James, the Pocomoke, the Nanticoke, the Choptank, and the Chester. Smaller rivers include the Elk at the head of the Bay, the Gunpowder near Aberdeen Proving Ground north of Baltimore, the Severn and South Rivers at Annapolis, the Piankatank and the Nansemond in Tidewater, Virginia, and the Sassafras on the Eastern Shore. There are two small Wicomico Rivers. One feeds into the north shore of the Potomac about twenty miles from its mouth. The other lies between the Pocomoke and the Nanticoke, with the Ellis Bay Wildlife Management Area at its mouth. Mostly marsh and forested wetland, this three thousand-acre haven for ducks, wading birds, deer and smaller animals is one of many lands left behind by time on the Eastern Shore. Lands that will be submerged under rising sea levels.

I can see no practical way to embark on a walk like this. Using Google Earth, I gauge the perimeter of the watershed to be a rugged line through valleys and mountains, cities, suburbs and farm fields, measuring approximately seventeen hundred miles. By comparison, the famed Pilgrimage Route (Camino) of Santiago de Compostela winds its way across Northern Spain for five hundred miles. People embark on this walk with motivations varying from spiritual to sporting. It’s usually done in thirty to forty days, for an average of twelve to seventeen miles per day—roughly half the daily distance of most of the Water Walks. This is the granularity with which such adventures must be considered. People have been walking this route since the Middle Ages, staying in quaint Albergues and Refugios, gorging on local food and basking in the scenery of ancient landscapes and villages. Probably not how a Bay Watershed Walk would go.

The Appalachian Trail also comes to mind. It runs from Springer Mountain in Georgia to Mount Katahdin in Maine, and measures about twenty-two hundred miles. Every year, “thru-hikers” attempt to walk it in a single season, usually from south to north to follow the weather as it warms. This takes at least six months, not to mention the training and preparation beforehand. Some avid long-distance hikers go for the “Triple Crown” of hiking, completing the Continental Divide Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail, which measure thirty-one hundred and two thousand six hundred and sixty three miles respectively. Seeing those numbers makes me think this might be possible.

Until I remember that none of my walk would be on public trails, maintained by parks departments, nonprofit environmental groups and scout troops. I had hoped that the Chesapeake Blessing Walk would at least follow the Appalachian Trail in the mountains of Virginia, Maryland or West Virginia. Alas, a quick superimposition of the two maps in Photoshop reveals that the A.T. neatly bisects the Bay Watershed.

Gradually, others join the walk, women and men. They too hear the song of the Chesapeake. Together, the people walk along shorelines of sand and stones, of hard paving, manicured lawns and tall marsh grasses. They say blessings and sing prayers, perform ceremony and gaze upon the Chesapeake and her many tributaries in wonder. They converse with the spirits that dance in the sunlight on the water’s surface and with the shifting tides in the depths below.

Hart-Miller Island – Julie Gabrielli

Hart-Miller Island – Julie GabrielliRather than choosing between shoreline, rivers, or watershed perimeter, why not walk it all? Why not here, there and everywhere? It’s the least we can do, after the last four hundred years of ignorance. We have the science-based advocacy, the citizen activist teams, the interactive web maps to track stream health and bird and butterfly migrations. We have the license plates and highway signs and storm drain stencils. Why not keep going and try everything that comes to mind, get all hands on deck? What have we got to lose? The places we love just might save us. Or at least they will change us.

As we walk, pray, and sing our blessings to the land and the water, we feel our own bodies and hearts becoming more whole and vibrant. When we return from our walks, we raise oysters and restore the grasses that have been lost. We plant trees and care for streams in towns and cities far from the Bay’s shores. Some of us tend gardens; others turn panels to the sun and blades to the wind. We walk and sing and share more. Our dances cause more cracks to appear in the crust, and more healing plants emerge. People are inspired to tear up paving wherever they find it.

And on it goes, as the oysters multiply. The Chesapeake is well pleased that she and her rivers run clear again. The cormorants and osprey, herons and geese and Monarchs once again fill the skies. The blue crabs thrive because the grasses have grown thick. Even the rockfish and the sturgeon return in great numbers. And we do not blush to bless a glass of water before drinking it nor find it strange to sit in hushed stillness under the sky that arcs over the Mother of Waters, bowing our heads in thanks as day becomes night.

About the Author

Julie Gabrielli has practiced and taught architecture with a focus on sustainable design for over twenty-five years. She was a faculty advisor for the University of Maryland’s 2007 Solar Decathlon entry, LEAFHouse, which place second overall, first in the U.S. The essays and paintings on her blog, Thriving on the Threshold, explore the both/and territory of living between cultural stories. In her Restorying retreats, participants experience sensory and imaginative kinship with the wild, animate world and practice listening for stories from the land. Her writing has been published online, in magazines including Ecological Home Ideas and Urbanite, and in the Dark Mountain Journal #6 and #8. She counts on her teenage son and her novel-in-progress for frequent lessons in humility.

juliegabrielli.com

Return to top