I put out apples for the dead last morning. Cut in half, two rounds of sweet flesh, twin star-wombs nestling tiny brown seeds. The rounds were uneaten this morning. I guess they haven’t come by yet, unless they’ve grown finicky basking in my attentions. Unless I have not yet found a way to feed them well. I’ve prayed, sung, pleaded, offered and even made my case as I’ve heard the indigenous sometimes do, yet of late they’re not speaking to me and I miss them.

Unless the wind just now is their answer to my call, the wind that swirls down dead leaves in a rattle of descent against a grey, storm portent of a sky. Unless the scavenging of the squirrels in the same dry leaves, nosing into cold earth for acorns is an answer. Unless the thin tissue voice of the corn stalks is them whispering, we’re here. And now the late-day sun finds its way through the dark clouds. The wind has stilled. Is that you?

The world speaks to us in a language I long to know, to hear. It’s a good thing the dead love our longing for them. It would be a good thing, too, if the living kept the gate cracked.

Why? And by what authority do you say that? Someone asks, someone who lives in my mind, Why carry the dead? What on earth for? She is persistent and I suspect she too is my inheritance.

Because, I say to her again, if I am the sprout of their planting, how can I not carry them? How can I forget them?

At any rate, I cannot help myself. I cannot help the persistent call to the web of my origins. I want to know who and what I belong to. And who belongs to me. And besides, if you cut a piece of the web, without repair, it falls apart. Until I make that repair, I am a clanless, tribeless woman and I know it. This is a dangerous condition, afflicting many, cut loose from any obligation to carry the past, to ensure a future. A world gone rogue.

I have always known that something is inside of me, someone lives in this skin house, someone calls to me in these bones. But it is dark in here and the voices far away through time. I hear weeping. I see grey granite sheared and plunging down, a steep chasm, a mountain? I hear weeping. Is it my own? Is it my dead come in the night?

I dream of an old woman with white and luminous hair. She is surrounded by young people who attend the feast of her dying, the rhythm of her breath straining through cheesecloth lungs. This is the instruction to me — attend to the oracle of her breath — keep my finger on the red circle inscribed before me until she releases her last breath. I do. She does. I leave.

I dream an old woman who tells me my unacknowledged grief is terrible.

I dream that CS Lewis of A Grief Remembered has given me his room.

I dream of my dead returning to me.

I dream of grief bowls made of earth, sold in the village marketplace where we pay our debts to creation. In the carrying of them, peace is created between neighbors.

I dream of collecting death teachings with a dying woman.

I dream of carrying a human skull, memento mori, remember death.

I dream of crossing the bridge of tears, her daughter and I guiding my friend to the other side.

I dream I am dancing, swaying with a dead man in my arms. A Pieta.

I dream of probiotics for the dead.

I dream I tell someone there are old ways to touch the dead.

I dream of an otherworldly café, I am lost, I am afraid, I’ve made a mistake, I want to go back. The GPS fails. The roads are icy and I skid. I ask a woman for help, she tells me she cannot help me go south. I am traveling North.

I dream. I dream. I dream.

Following the instructions of a teacher, I look for my dead, their tracings, in the old ways of my people. I study Scots Gaelic in which I learn that my ancestors did not say my land, my house, my family, my. Other than for relatives and the body they did not express possession in that way. They literally expressed connection by saying someone or thing is on me, with me, at me. An echo of all my relations. The dead are at me. They surely are.

I try my hand at the drop spindle, the most ancient form of spinning. I hook the roving to the spindle, draw out the fibers and spin the spindle sunwise. I imagine spinning the thread of creation; as the spiral of energy travels up the wool I pray to renew the world and make holy the daily life. I spin, I pray, all to weave myself back to them. I write. I sing. I call to my dead in their language, I introduce myself and the dog who is with me.

I am trying to carry my dead. And, I don’t know how.

Some would say I am obsessed, and they would be right. Some would say it is a distraction. Perhaps. But this is what I know. It is the story that has conjured me my whole life, that has tried to plant itself in the stubborn soil of my heart. A heart harrowed by grief — both the proper grief that calls to those gone from my sight, and the sorrowful wreckage that I inevitably caused when running from that grief.

I surrendered to my grief many years ago, I had no choice, on my knees in the garden unable to move for the pain, and in doing so tried to heal it. In Western ways, that means I put myself to the task of disappearing it, killing it with kindness, drowning it in tears, purging it with catharsis, and boring it to death with analytic repetition — all in the name of healing. But grief’s faithfulness was carried on the back of my necessary failure. Grief is meant to grow something, it seems.

Yet, the seed has taken this many years to root. It is fragile. Will there be time? It is a calling no one has asked me to take up. Except, perhaps, my dead? It is, by necessity, in these times, a solitary work. It is lonely. And I don’t know how.

I search in the old way. I circumambulate. I circle around.

I take the light and move from room to room in this haunted house that I am, tracking my own dusty footprints looking for signs of them. The light reaches deep in the corners, shadows loom and I wait.

She shows herself in a dream.

There is a wolf, who is a woman, who is a wolf. She lives behind a wall in my mind. She steps out, she looks at me and in her fierce gaze she tells me to knock it off, this doubt, this worry. She has come a long way. She has been waiting for me and my lantern. There is work to take up.

When she arrived I do not know, perhaps she was a seed, a dream, a song carried in the egg basket of my mother, that tiny pocket woven with flesh and blood, filled by other-worldly hands, the midwives of fate, with oracles. With me.

I am coming to know her, the one with a name only known to the spirits. How did they know that she, the one who lives behind the wall in my mind, would be needed. Now. At just this time. For these times.

She follows the tracks of the disappeared stories, the exiled names, the stolen children, she laments the lost heart, she might even return it to you. I see her. Her throat is open, there is a rope, a thread, an umbilicus, twisted by the spindle of stories we do not want to hear, but must. She is the throat woman, the spinning song woman, she wraps the lost, the missing, the forgotten in the silk of her spinning lament and brings them to the living.

The pitted earth is the throat of the keening woman: the test pits, the uranium pit, the mined earth gouged with our longing. Out of the throat of the keening woman comes everything you did not know you longed for. Out of the throat of the keening woman comes everything we destroyed in our innocent desire for a good life.

She is the throat woman, the spinning song woman, she wraps the lost, the missing, the forgotten, in the silk of her spinning lament and carries them home. But first we must hear her cry, be shattered by the ululation of her grief. Then maybe all will be whole.

She is faithful, she has called to me through death, the flood of my own longing, the floating wreckage of history. Like luminous moths battering against the light in soul darkness, she is faithful. She is wolf, she is woman, howling. She spins the thread of return; her throat is a whirlpool, her voice keening, wild.

I see now, she rocked with me when my beloveds died. She lamented. Oh, do not pity me. They died, the gate opened, she saw her chance, stepping through and into a child’s lament. She has been the unknown walking stick of my journey; she is the singer, the finder of lost sorrows, the weaver of memory; she lives in the underside of history’s tapestry, the underworld of our dreams.

I heard her once in the death lodge in the voices of rain and thunder. Lightning. I thought I’d imagined it.

She is of my people. The Keening Woman. And I belong to her.

I walk up the hill in these small woods and I lay down tobacco, I lay down corn meal and mead, I pour whiskey, and I sing a mourning song. And I ask her to teach me.

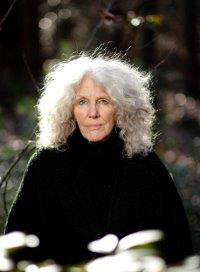

About the Author

Nora Jamieson lives in Northwest Connecticut where she writes, counsels women, and unsuccessfully tracks coyote. She is the author of a book of short stories, Deranged, and lives with her spouse Allan Johnson, their young and soulful dog Roxie and with the sorrowful and joyful memory of four beloved goats and three dogs.

www.norajamieson.com

Return to top