These paintings, inspired by Iranian artist Naeemaei’s concern for the endangered species of Iran, were part of a series shown in an exhibition at the Henna Art Gallery in Tehran. The entire series is collected in Dreams Before Extinction, a book edited by Paul Semonin in collaboration with the artist and published by Perceval Press in 2013. Written commentary by Naeemaei accompanies each of the paintings.

In the introduction to Dreams Before Extinction, Paul Semonin writes,

Painted in a dreamlike, figurative style that is disarming in its sincerity, the images bring together many different elements of Iranian culture, from religious ritual and sacred scriptures to folk tales and children’s stories. “I use my dreams, wishes, memorabilia and legend, plus information about the species, to extend my imagination,” [Naeemaei] says. “In each painting, I’ve lived with an animal in my mind. It is a deep connection.” In effect, she is asking us to do the same, to identify with the animals in a more personal way, as though they were part of our family.

Dreaming becomes a powerful medium of communication, both for her personally and for the viewers of these artworks. Dreams take us out of the comfortable region of the conscious mind to a mental and physical place where emotion comes into play much more readily. In many ways, Naeemaei is saying that the purely logical mind has its limitations when it comes to expressing the pain and grief she herself feels at the loss of these species, or the damage our way of life causes to the natural world up on which all life depends.

* * *

SIBERIAN CRANE

Acrylic and oil on canvas, 2011, 152 x 210 cm

They say that he is the very last one! The Siberian Crane is a traveler from Russia that comes to the coast of the Caspian Sea in Iran to spend the winter each year. His Persian name is “Omid,” which means “hope.” The book I am holding over the crane’s head is the Koran. Traditionally the Koran is held over the head of a person who is leaving the house for a journey, to make sure s/he will return safely. I am using this custom, which is common in Iran today, to ensure the crane will come back next fall. It was the only thing I could do, as a mother, sister, or a wife, whichever you may.

* * *

IMPERIAL EAGLE

Acrylic and oil on canvas, 2011, 94 x 210 cm

An art critic once asked me: Have you paid attention to the symbolic meaning of the animals in your paintings? Did you think of the power of the Caspian Tiger or the symbolism of the Imperial Eagle in your paintings of these animals? Are you interested in wild and powerful animals? Do you believe in their legendary powers? He guessed that my general ideas were taken from the symbolic values of each animal. I told him, No! I don’t care. I am happy if the symbols match my animals, but to me all animals, even the seemingly weak ones, are as real and powerful as any other in the real world.

* * *

CASPIAN RED DEER #1

Acrylic and oil on canvas, 2010, 205 x 146 cm

For me, the Caspian Red Deer is a mysterious animal. I had eaten its meat in my childhood and had seen his antlers in my paternal relatives’ houses, but I had never seen his picture. I didn’t know his name or what he looked like? The dark background of this painting is an image I had in mind from outside my grandma’s house during a cold autumn, her house being located right in this animal’s habitat! My uncles are hunters and they don’t listen to my bemoaning them not to hunt. I had those antlers, so I decided to be the body of the animal himself, to be buried under a tree respectfully with him. And perhaps I wanted to say to my uncles: “We are one! Bury us together or stop killing us.”

* * *

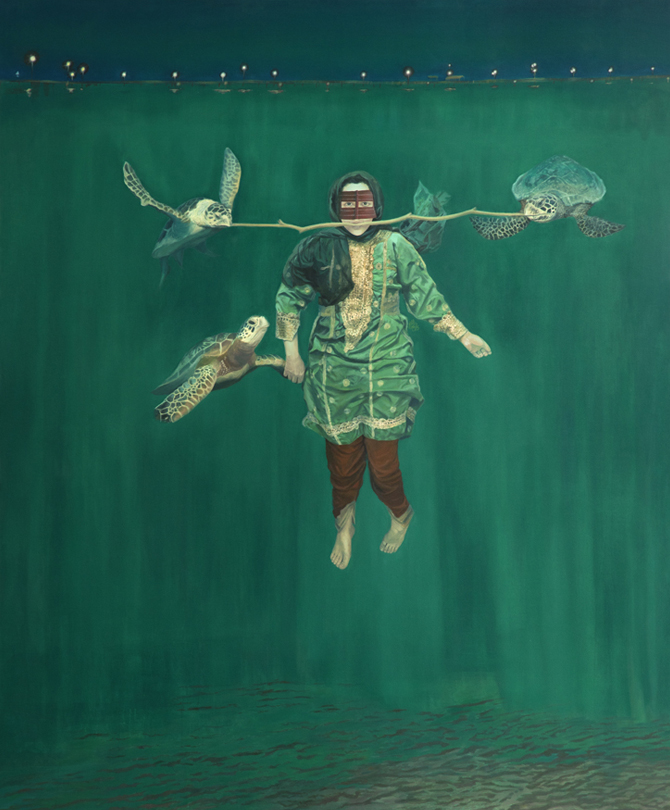

HAWKSBILL TURTLE

Acrylic and oil on canvas, 2011, 190 x 160 cm

“The Turtle and the Geese.” In Iran this story is found in the tales of “Kalila and Dimna,” from the Panchatantra, an Indian collection of ancient animal fables. Once upon a time there was a turtle who lived in a pond that was going dry. The turtle asked two geese for help, and they agreed to fly him to another pond. They held a stick in their beaks while the turtle was hanging onto it by his mouth. The geese warned the turtle that he must remember not to open his mouth, lest he would fall. While the geese were transporting him in the air across the countryside, a group of children down below burst into laughter at the funny sight. The turtle became angry at their rude remarks and opened his mouth to reply but fell from the sky to his death. If you don’t mind, I would like to change the old story to make my own story. In a new version of the Panchatantra, I play the role of the turtle, and the blue sea plays the part of the sky. The turtles help me to fly in the sea, and I guide them far away from the roads and artificial lights on the shoreline, a form of light pollution that disorients newborn turtles, sending them inland to their deaths rather than to life in the sea. I don’t want them to remain endangered. I want them to live and flourish.

* * *

PERSIAN STURGEON

Acrylic and oil on canvas, 2011, 190 x 125 cm

This painting is the only nightmare in the series. You can predict the end. The net will definitely fall. The old house in the painting is my maternal grandma’s house in an old sector of Tehran. It is located in a narrow alley with a little stream running through it. When I was about five years old, I used to sit on the stairs watching that small, dirty stream, waiting for a fish to pass by! I even tied a rope to a branch to fish there. How foolish! How hopeful! The sturgeon lives in the Caspian Sea and is valued mainly for its caviar. The Caspian Sea is actually a closed lake and is getting more polluted every day. The problem began after the Soviet breakup when the new countries around the lake put aside any restraint in fishing sturgeon. I have brought the Caspian Sea to my grandma’s alley to be with the sturgeon there. And, as in a nightmare, the fisherman comes out of the windows above to fish us. I hug the sturgeon to be with her, to be part of the same destiny. Under the net…it is a ruined dream.

* * *

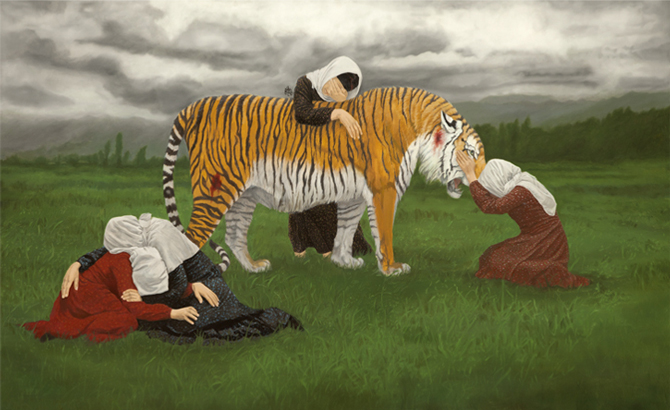

CASPIAN TIGER

Acrylic and oil on canvas, 2011, 117 x 190 cm

In his habitat he was called the “Red Lion.” Actually he wasn’t a lion, but I must admit that he was red; he was bloody. The last one was killed in 1959, but there was no funeral and no one cried. I don’t know where his tomb is to put flowers on it. I can only wail and mourn his passing in my own way.

* * *

LORESTAN MOUNTAIN NEWT

Acrylic and oil on canvas, 2011, 218 x 160 cm

This is the most introspective painting in the series, and the only abstract one. I am in the center with many salamanders linked to me by black and red threads. We have many things in common: the patterns on the backs of salamanders, the design of the costume from Lorestan province that I am wearing, the lines of my wavy hair, and my blood veins that connect me to the red pattern of the salamander’s back. I’ve tried to gather all of them around me, to connect our blood, our body, and our destiny.

About the Author

Naeemeh Naeemaei’s – paintings and sculptures have been widely exhibited in Tehran. She has also had exhibitions in Berlin and Eugene, Oregon. She received her B.A. in sculpture from Tehran Art University in 2006. The subject of her last series of sculptures at the university was “the decay of plants.” She is active in Iran’s environmental movement and involved with several organizations that seek to raise awareness about endangered species and other environmental issues. “I want to make some changes at least in my own people about their behavior with regard to nature and the environment. Even for just a bit!” she says.

naeemeh.naeemaei@yahoo.com

Return to top