Home now. Or was that home? And what did I carry home from New Hampshire beside the dried and unworked hide now tacked to the board. The yearling doe hide, who was flesh, who was a fawn, who was a wet and gangly newborn, who was carried and loved, who was the meeting of an egg and a sperm, who was a longing, who was a possibility. No more.

Who was sighted, shot, skinned, quartered, or bled out to age the meat, whose skin under my hands was fleshed and grained and soaked and smoked and will be stretched again and again over the coming winter, my hands raw and bleeding. Whose lovely head might be one of many in a large vat of heads that will feed chickadee and vulture and coyote.

I enter after the kill, after the hunter’s early rising, the coffee and eggs, the toast at the local diner, before filling up the thermos, heading out to the woods, before climbing up into the tree stand. Before the waiting, before the sighting, before the shot. I arrive after the soft crumple, the violent spasm, the instant death, the slow one.

I arrive after the tents have been pitched, the food delivered to the kitchen, the smoke house fires lit, the selection of the hide carefully saved out for me. After the morning prayers and coffee and smokes, I arrive in the temporary village, too gentle a term for all that has happened before me. Children run about. Dogs prance, showing off the prized legs of deer, or wait hopefully for bits of fat to fall to the ground.

Like a paper doll inserted into a scene, I arrive to that small village of men and women in deep concentration, hunched over fleshing beams, working hides with dull crescent-moon blades, carefully, so as not to tear the thin places, perhaps knowing the debt owed to the hide that might just as much have yearned to return to earth.

How do we justify, understand what we do? A wise fool of a man once said, the holy life, the sanctified life, is not one without trespass, it is knowing the debt we owe. And how do I carry that debt and all the debts owing to one small act of fleshing a hide on a snow-squall morning in New Hampshire?

It could make a woman crazy trying to keep count of all the ways she is indebted to that one morning and all the elements that came together to weave it. So many threads on the loom. The sun thought it a good idea to meet the earth as she again, graciously, even at such cost now, turned her face to him who some call Grandfather. Wind joined in, swirling snow around us as we remembered with longing the old iron stove in the barn that someone thought to light with trees taken to keep us warm. Everyone is somebody’s child, the tree the child of the seed, the iron extracted from earth’s core, forged with fire and that fire fed, too. So many debts.

And the dead, I know, walked among us. And within us. Awakened by the aroma, this feast of the old ways, seeing through the plastic, the fleece and thermal space age gear, taking their place in the circle of women, holding a large hide between them, stretching and working it, bouncing a child in the center. The dead entering the hands of the women kneading the fibers apart as they did then. This is how, this is the motion, this is the way.

Yes, I am sure the dead were there. Perhaps it was their idea, let’s give them a taste of how it used to be before thinsulate, before plastic and prefab houses. Before the lie was told that the gods are dead. Let’s make them hungry for us.

And so I fleshed, up and down, listening to the conversations among the young around me yearning to find a way to live that makes sense. But I cannot remember a single word. Just the motion, the debt, the hides, and the sturdy blond woman walking the November field, playing the wailing bagpipes, and the men singing the high–pitched keening at the Mother Drum.

Perhaps this is how remembering works.

Do this. Up and down, back and forth. Now. You remember.

Notes:

I support animal protection, sign petitions against zoos and aquariums, oppose sports hunting and killing contests. I am also called to bone and pelt and my old ones. Many years ago, I thought the remedy to planetary devastation wrought by humans was to follow certain conceptual, political and spiritual prescriptions in order to restore the world. And maybe that is one way.

Yet I am compelled to follow the old ones who are calling me into their ways, and so I flesh the hide, I pray, and I daven in this field of death out of which life comes. I know that some of these deer were taken in an unholy way, and so both the doing and the writing are a work of reparation, a work of blessing the dead, acknowledging the debt, honoring the life.

“Fleshing the Hide” is excerpted from a larger piece I am writing, with the working title of Walking Into My (Old) Soul, inspired by my friend, Anne Batterson, who, when I told her about this village, said “it sounds like you walked into your own mind,” and I thought, yes, my own Soul.

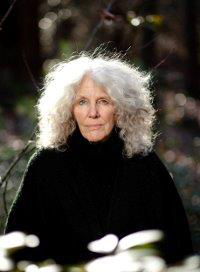

About the Author

Nora L. Jamieson lives in Northwest Connecticut where she writes, holds councils with women, and unsuccessfully tracks coyote. She lives with her spouse Allan Johnson, their young and soulful dog, Roxie, and with the sorrowful and joyful memory of four beloved goats and three dogs. Her book Deranged is forthcoming from Weeping Coyote Press.

www.norajamieson.com

Return to top