Managed retreat, or the voluntary movement and transition of people and ecosystems away from vulnerable coastal areas, is increasingly becoming part of the conversation as coastal states and communities face difficult questions on how best to protect people, development, infrastructure, and coastal ecosystems from sea-level rise, flooding, and land loss.

The Georgetown Climate Center

“Breaking Wave,” oil on linen by Aviva Rahmani, 76″ x 86″, 1994

“Breaking Wave,” oil on linen by Aviva Rahmani, 76″ x 86″, 1994

Winter 1989 found me in a state of desperation about our environment. I left the large loft where I had been living in Park Slope Brooklyn to make a dramatic art statement about climate change and threatened global water systems. I had pored over maps of aquifers and waterways across the US to find a place where I could live without stealing water from indigenous peoples. In a dream one night I traveled along the waterways in those maps to a place off the New England seaboard. My destination became the remote island of Vinalhaven, fifteen miles out to sea in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Maine, where I hoped for answers and refuge.

As soon as I arrived, I began six months of documenting coastal fog in daily photographs and text for a project I called “Safety.” I thought fog might teach me something about managing the future I feared because fog obscures reality. But my conclusion at the end of that work was that denial feels safest for most people. Denial can also bring people to the brink of the desperation that was still driving me. By the time I figured this out, the island had captured my imagination, body and soul. I have lived here ever since.

If “Safety” didn’t deliver any comforting insight about where to find refuge, the project did get me thinking about this place at an end of the Earth. The island’s fragile water system is a sole source aquifer beneath scant soil. An even more serious potential threat from sea level rise is salt water intrusion. I thought I might start pushing back from here against the dangers of climate change. I also got chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) soon after arriving which complicated my every decision and action. That illness heightened my sense of vigilance and sensory awareness and required me to carefully strategize how to manage my stamina.

“Bed of Nets”, 1991. An installation of ghostnets I found in one of the island’s dumps.

“Bed of Nets”, 1991. An installation of ghostnets I found in one of the island’s dumps.

On the island, I learned about the lost monofilament fishing drift nets called “ghostnets,” invisible when under water. These nets seemed a perfect metaphor for the complex habits of thought and action that are invisible to us but trap us in our dangerous anthropogenic attitudes. Once loose from fishing vessels, the nets go on fishing bycatch of marine birds, seals, dolphins and fish for seven years, strip-mining the ocean of life. I committed to my next project by the same name “Ghost Nets” (1990-2000), knowing it would be a long haul. I resolved to challenge every routine of thought and behavior in myself that might mask my own denials of danger.

My first action for “Ghost Nets” was to buy the former town dump and begin building a tiny post beam house on a granite ledge at the site, where I have lived ever since. I had no funding so I sold a house I had built in California. I then began the slow work of restoring the 2.5 acres I now owned as an act of artmaking as I learned to live with CFS, aware that my acres provided habitat contiguity for a much larger swath of coastline in the Gulf of Maine. My intention was to save a corner of the Earth. I believed the attention I would give to this one small site might catalyze healing for a much larger landscape and rescue me from my desperation.

My next action on the land was to purchase and plant 400 tree saplings of primarily indigenous and selected exotic varieties suitable for adaptation to climate change, to replace the wood I had used for constructing my home. I was inspired by the precepts of serenity and surprise of Asian landscaping but I also conceived the work as movements in a symphony of time and space. I planted the saplings in a concentric windbreak pattern extending out from one small vernal spring in the center of the project site. On the daily I traversed the paths I had built through the 400 trees, greeting and honoring each of my plantings in their beds, often speaking to each one and noting their respective growth or demise. I observed the occasional indigenous volunteers, gravely considered nurse relationships between species, and inhaled the constantly shifting fragrances of each day. Occasionally I attempted to harmonize my vocalizations with bird songs. In the first three years I filled four large notebooks like a nineteenth century naturalist documenting each sapling planted and the thousands of seeds and seedlings. I tracked the progress of transformation even as I meticulously journaled my own unsteady recovery from CFS. With time, the music of the site swelled, teaching me to seriously listen to the land and to myself.

Left, an oak sapling planted in mycorrhizae, 1991. Above, standing with grown trees in the mature garden, 2009.

Left, an oak sapling planted in mycorrhizae, 1991. Above, standing with grown trees in the mature garden, 2009.

As I planted the 400 trees, nestling them in swaddlings of newspaper saturated with liquid mycorrhizae, I could see that erosion was the most imminent threat to the soil I meant to build. Spring melt drains downhill into the sea at the extreme southern tip of the site. My next task presented itself, to slow this erosion by restoring the uplands riparian zone. I laced the terrain with stroll paths and gardens, placing large boulders to strategically slow erosion and taking lessons from the site about what it needed.

The former sawmill at the foot of the “Ghost Nets” site became my art studio, the personal climax of all my efforts. The building was on made land that extended into the cold north Atlantic waters, making a deep-water wharf, one of several wharfs on Vinalhaven Island that had carried finished granite columns to the great monuments of the city of my birth, like the New York Public Library and St John’s Cathedral. The irony was not lost on me. The estuary just scant feet from my studio had been buried under the granite tailings leftover from the monumental exported columns and manmade land. I passed its choked mouth each day en route to the studio from my house.

I shared the wharf with Ira Greenlaw, my land partner for the first several years and a local fisherman. At the end of each day Ira and I visited for a few minutes. He taught me how the offshore marine eelgrass meadows completed the picture of habitat fecundity that was forming in my mind connecting mainland habitat, the sea and the island’s estuaries. With the help of bioengineer Wendi Goldsmith, I started to plan how to restore the buried estuary at the site by removing the granite tailings. I hoped that work would nurture eelgrass.

Left and top, boulders and tailings from Vinalhaven’s granite industry littering shorelines and blocking estuaries. Above, “Blue Rocks” that helped lead to restoring 27 acres by the USDA, 2002.

As I worked on daylighting the estuary, I was thinking of how our culture casually consumes and disposes of the beauty and fertility of young women as analogous to our treatment of wetlands beauty and fertility. I began to plan what would become the final task for “Ghost Nets” as “the restoration of the ultimate cunt.” I was not the first feminist to conjecture how the c-word reflects the denial of female power or to identify sexism and patriarchy with institutions that promote ecocide. But as a rape survivor, I was acutely sensitized to the shock value of the term “cunt” and how the c-word has been a means to subordinate, demean, and shame women as disposable property, just as the estuary by my studio had been subordinated, demeaned and literally trashed with granite tailings as disposable property to make the town dump. Historically fish and a woman’s sexuality are also often associated with the scent of the sea. Wetlands are the wombs of the Earth. At the “Ghost Nets” site I noted how the topography was now providing passive shelter and accumulated water and soil for more wildlife. When I applied the same restoration thinking to my next project on the island “Blue Rocks” (2002), I was thrilled to witness again the revival of abundant wildlife. My work redefined ‘cunt.’ It became, ‘richly fertile.’

The “Blue Rocks” restored estuary with flourishing marsh grass, 2012

The “Blue Rocks” restored estuary with flourishing marsh grass, 2012

White stones marking the trigger point where freshwater and saltwater met again for the first time in a century after granite tailings were removed (“Ghost Nets”, 1997)

White stones marking the trigger point where freshwater and saltwater met again for the first time in a century after granite tailings were removed (“Ghost Nets”, 1997)

The mouth of the “Ghost Nets” estuary became my first experiment in what I later developed as “trigger point theory,” after the acupuncture treatments I was receiving to help heal my CFS. The currents in the meridians of my body whose free energetic flow ensured my vitality were like the island’s waterways, ensuring its vitality. Both systems have points where this vitality could be blocked or triggered. I came to see how restoring one critical point to its original functionality could revitalize an entire swath of contiguous habitat. The “Ghost Nets” site was guiding me to seriously observe, listen to, and smell the healing land and waters, and extrapolate those pragmatic trigger points. I was becoming teachable.

As I worked year by year on “Ghost Nets” I settled into island life. I joined the choir at the local church, which inspired me to study operatic bel canto. This arduous vocal training informed how carefully I heard ambient sound on the site, and eventually my whole eco-art practice. The vocal training also helped rebuild my physical resilience from CFS, teaching me to breathe with my body, with the land and with each new place I visited and studied, on and off island. As my senses internalized the site’s layered lessons, my mind tracked the implications of the changes I was observing. My now decade-long work on “Ghost Nets” could be spun off into a series of works, at first mostly off island, marked by noting how fish are endemic indicators of ecological health in most water systems. Attending conferences, I started to research and experiment at other sites with how geomorphic features might effect passive restoration of degraded landscapes. My understanding of “Trigger Point Theory” evolved as an aspect of how I came to understand complexity theory and quantum mechanics.

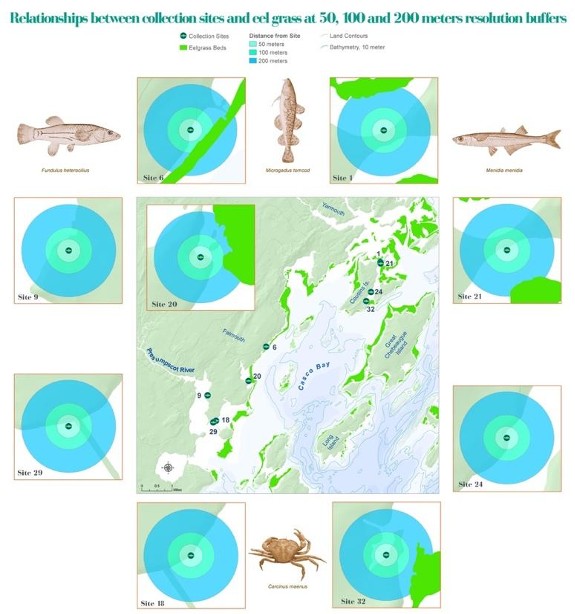

Above, the center map with blue dots represents study sites for finfish abundance in relation to eel grass and predatory European green crabs in the Southern Gulf of Maine. The surrounding circles are GIS analyses of how species were impacted by those interactions at each site (Trigger Point research with Hope Rowan, 2016). Below righ, water flowing again in the USDA’s reopened causeway after “Blue Rocks’, 2004

Above, the center map with blue dots represents study sites for finfish abundance in relation to eel grass and predatory European green crabs in the Southern Gulf of Maine. The surrounding circles are GIS analyses of how species were impacted by those interactions at each site (Trigger Point research with Hope Rowan, 2016). Below righ, water flowing again in the USDA’s reopened causeway after “Blue Rocks’, 2004

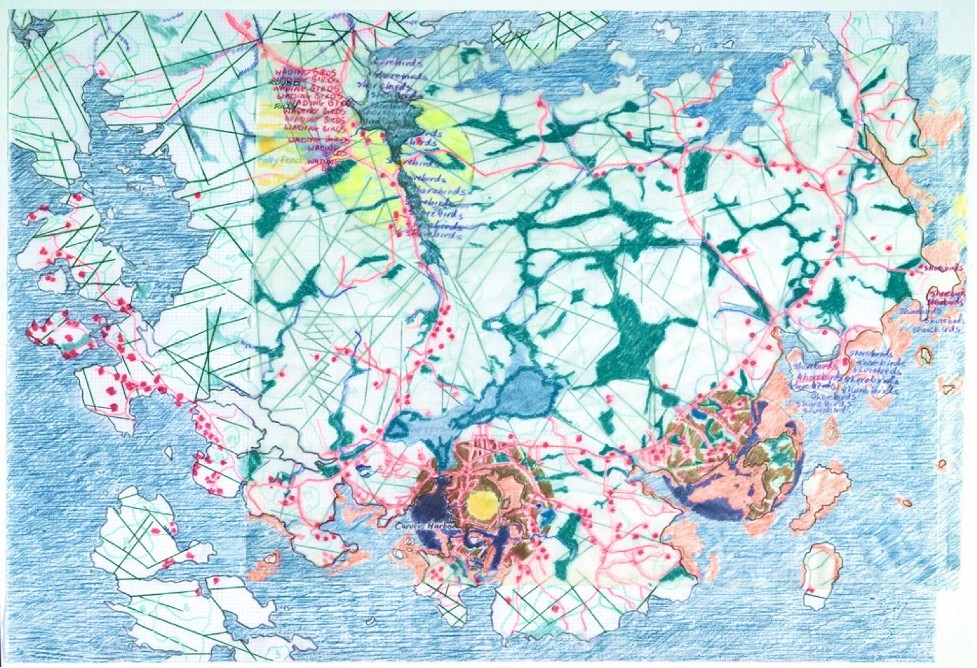

My working premise was that art could deliberately precipitate a butterfly effect by fostering attention to specific sites: trigger points on the meridians of the Earth. I envisioned how a series of trigger point restorations could catalyze large landscape habitat contiguity. When “Ghost Nets” inspired my next project on the island “Blue Rocks”, I used Geographic Information Systems (GIS) mapping to determine where opening a causeway to greater tidal flushing could effect maximum healthy habitat far beyond the two and a half acres of “Ghost Nets” to restore thirty additional acres of critically located wetlands.

By overlaying different GIS natural resource maps, I also saw proof that the modest regional effect of “Ghost Nets” combined with the much larger “Blue Rocks” site might have cumulative overlapping impacts on the entire adjacent locations in the Gulf of Maine. When the local Land Trust subsequently partnered with the USDA to open the trigger-point causeway as I had conjectured with my “Blue Rocks” GIS mapping research as art, we saw biodiversity flourish, reinforcing my premise about the efficiency of applying trigger-point theory to large landscape restoration. Connecting the biogeomorphic dots in “Ghost Nets” and “Blue Rocks” into larger landscapes also coincided with my regaining enough physical stamina to engage in a bigger world despite CFS.

Above, a colored drawing based on studies of GIS mapping of natural resources comparing biodiversity at three different sites on Vinalhaven Island, including bottom right circle “Ghost Nets”, top center circle “Blue Rocks” and bottom left circle the Ferry Terminal access site to the Island. Research for “Blue Rocks”, 2002.

Above, a colored drawing based on studies of GIS mapping of natural resources comparing biodiversity at three different sites on Vinalhaven Island, including bottom right circle “Ghost Nets”, top center circle “Blue Rocks” and bottom left circle the Ferry Terminal access site to the Island. Research for “Blue Rocks”, 2002.

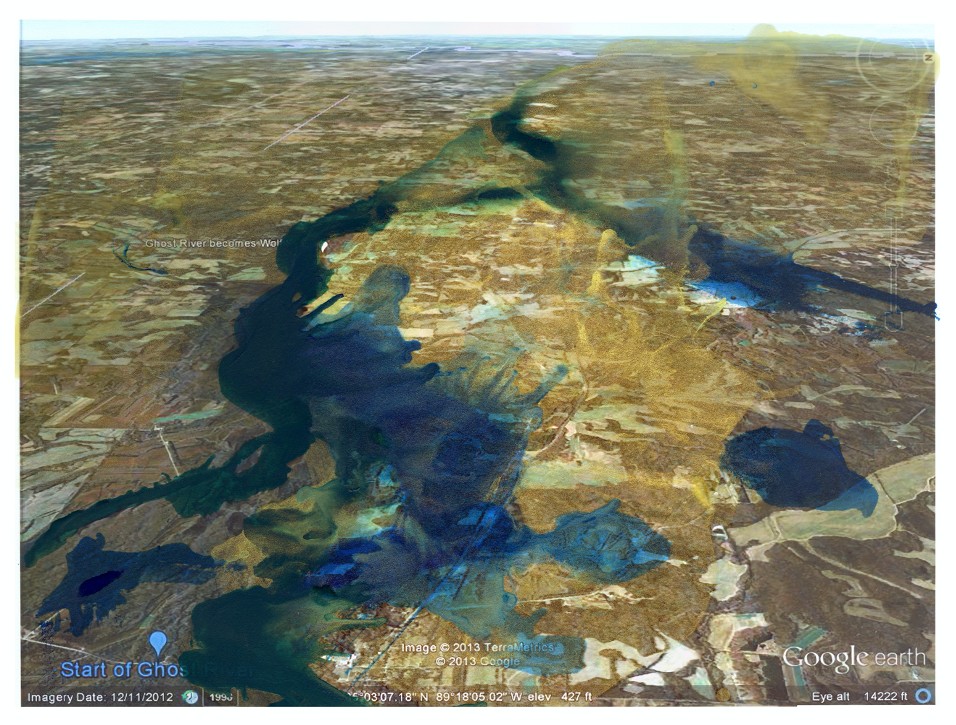

The deeper my roots took purchase in the granitic soil of the island, the wider my own mycorrhizae interests expanded to include larger biogeographic systems and fundamental systems of environmental justice and Earth rights. After Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005, I traveled to Baton Rouge for a conference on deltaic systems where I met the wetlands scientist Eugene Turner. Later, with paleo-ecologist Jim White, we initiated “Fish Story Memphis,” using patterns of lost keystone fish species to identify a trigger point on the Wolf River, a tributary of the Mississippi that had been cut off from the river, to effect healing for dead and degraded wetland zones in the delta in the Gulf of Mexico.A decade later, the City of Memphis validated our collaborative research when the daylighting of the blocked passage between the Wolf and Mississippi rivers became a centerpiece of urban renewal.

Above, children delight in seeing the fish species that might return from restoring the blocked trigger point between the Wolf and Mississippi Rivers. Detail from “Memphis Fish Story”, The Memphis School of Art, curated by Tom McGlynn, 2013

Above, children delight in seeing the fish species that might return from restoring the blocked trigger point between the Wolf and Mississippi Rivers. Detail from “Memphis Fish Story”, The Memphis School of Art, curated by Tom McGlynn, 2013

In 2010, I began my PhD on “Trigger Point Theory as Aesthetic Activism” in a crossover between environmental science, technology and studio art. That same year I attended COP15 in Copenhagen with observer status. At the COP I was shaken to my core watching the infectious joy and hopes of activists crushed by state actors in collusion with fossil fuel corporations. I returned to Vinalhaven even more convinced that Trigger Point Theory was the key to broad systemic changes. It took another five years for me to see how that could lead to policy change. I needed to figure out how to legally challenge the fossil fuel corporations perpetrating ecocide. “Fish Story Memphis” and the acres of flourishing wetlands I saw on the island daily were all I needed to fuel my conviction.

Blue paint demarcates flooding in the Mississippi River Basin made worse by attempts to control the river by hardening the landscape. Encaustic on a Google Earth satellite photo, 11” x 17”, 2013.

Blue paint demarcates flooding in the Mississippi River Basin made worse by attempts to control the river by hardening the landscape. Encaustic on a Google Earth satellite photo, 11” x 17”, 2013.

A Deus Ex Machina also connected me in 2015 with a small group of New York State activists intent on stopping natural gas pipelines from traversing their upstate forests. I was propelled into new resistance. They were inspired by the sculptor Peter Von Tiesenhausen who was able to stop natural gas pipelines from going through his ranch in Alberta, Canada, by copyrighting the top six inches of soil. I too had studied copyright, trademark and patent law in the late seventies at the height of the appropriation movement in art. I could see the proposed pipeline corridors would criss-cross and irrevocably fragment the forests just as the dumped granite tailings had fragmented the estuaries on Vinalhaven. Key sentinel trees would be felled in the putative name of the “public” good. These corridors and the habitat contiguity they anchored as trigger points in the landscape would be destroyed. Building on Von Teisenhausen’s legal theory, I saw a way to leverage an abstract trigger point of overlap in copyright and property law between the inviolability of the spirit of art and the notion of the sacred home. My years of planting, walking, listening, watching, smelling, and sensing the “Ghost Nets” and “Blue Rocks” sites had prepared me to conceptualize trigger point theory as the spatial choreography of relationships between art, land ownership, and Earth rights. When I left the island to launch “The Blued Trees Symphony” project (2015-2018) I intended to stand with a range of environmental activists across the continent resisting fossil fuel corporations and hold them accountable for ecocide.

Eco-activist Linda Leeds painting a tree note for the overture of “The Blued Trees Symphony”.

Eco-activist Linda Leeds painting a tree note for the overture of “The Blued Trees Symphony”.

A sentinel Tree-Note in bloom in a measure of “The Blued Trees Symphony”, Saskatoon, Canada.

A sentinel Tree-Note in bloom in a measure of “The Blued Trees Symphony”, Saskatoon, Canada.

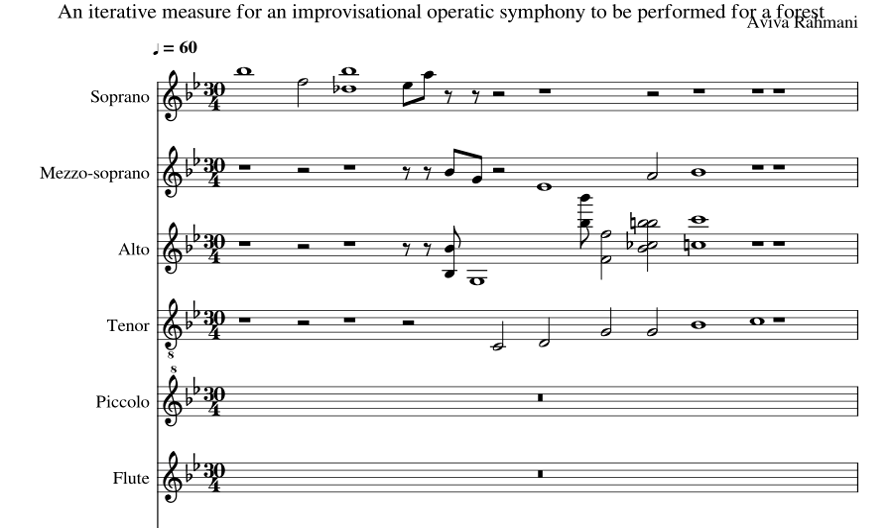

The project challenged familiar legal and aesthetic assumptions, and also musical theory. Eco-activists and I painted sentinel trees with a blue vertical sine wave in GPS located patterns that corresponded to the aerial score that the keystone blued “tree-notes” performed in the habitat. I translated this aerial into a performable musical score for orchestra. The score began in Peekskill, New York. The symphonic “score” was extended with teams of artists creating ⅓- mile- long measures from Saskatoon, Canada in the North West, to Washington State in the far West and Louisiana and Florida in the South. Later, I traced aspects of the project in art installations and research across the globe to imagine how to conserve international forest contiguity on land and sea to mitigate global warming. Whenever possible, I walked the forests as I had the paths of “Ghost Nets,” listening to the trees whispering to me of their fears and hopes. As I embraced their trunks to reach around to paint their textured barks, I watched the color layer itself in, heard the conversations of woodland life, deeply inhaled the aromas of buttermilk casein and foliage embracing my body back in its green garment.

Effecting policy change with art required establishing case-law precedent. Short of that goal, a mock trial can still test a new legal theory. My opportunity came in 2018 during a Contemplative Practice Fellowship awarded by A Blade of Grass. We coordinated a mock trial with copyright lawyer Gale Elston in the Cardozo School of Law, New York City. Real prosecuting lawyers argued to protect “The Blued Trees Symphony” copyright. The real judge ruled with the prosecutors. Her injunction protected the sentinel trigger point tree-notes in full musical measures in contiguous forest habitats in the path of pipeline corridors. We won against a hypothetical natural gas corporation, paving the way for a comparable verdict in a real courtroom, ideally in an international court ready to prosecute corporate ecocide. At each step of “The Blued Trees Symphony” I mustered courage to defy my limitations and at least one dark money threat that came in the mail. I felt I was defying the same denial that my first project “Safety” on Vinalhaven had revealed to me but at its fullest scale. I moved past the physical limitations imposed by CFS, living on fumes, to connect dots at the scale the real world needs and that I had intuited with “Ghost Nets” and “Blue Rocks.”

Overture of “The Blued Trees Symphony”, 2016

Overture of “The Blued Trees Symphony”, 2016

Since 2018 and inspired by that trial, I have worked on an experimental opera about ecocide, drawing on my decades of bel canto studies and what I learned about listening to sounds in “Ghost Nets.” I intend my opera to be another means to understand and communicate how place must inform policies for common good grounded in environmental justice and Earth rights on a continental scale.

Even as sea levels continue their rise, I have chosen to remain in place on Vinalhaven. Fierce storms routinely visit the Gulf of Maine in winter and spring. Waves routinely and violently pound the piers that support my studio, the old sawmill, on manmade land. Inside the building is my life’s work, two stories of art and materials crammed so full I can barely choreograph my own movement between the artifacts of my practice. Looking out over the ocean at a latitude of 440 N, I work just three feet from the deep waters of the North Atlantic and very near the Gulf Stream, the dominant current from Florida to Nova Scotia. If I were to continue East over the Atlantic, I would reach the beach of Lacanau Ocean at the end of Boulevard de la Plage, about 55 km northwest from Bordeaux, France, exactly 2,815.335 nautical miles away. Were a particularly fierce storm surge to hit my site, I might see my entire studio swept out to sea and my life’s work carried off to any place from Spain to France, or even further north in the direction of the Arctic, perhaps washing ashore in Ireland or Wales on the way, the remnants of my artifacts reduced to mere microscopic bits of flotsam.

View of the Old Sawmill, my studio, 2023

View of the Old Sawmill, my studio, 2023

I accept the fierceness of Mother Nature’s retaliation for our avarice and rapacity. I wake to redemptive light streaming through my bedroom windows with a view downhill to the shore through “Ghost Nets” and on to the sea past Matinicus Island. The light shifts daily for me to capture pictures of dawn. Smells are sharp. Air is distinctive to each season, informing me about the earth and her rhythms, the vitality of the trees, carrying the susurrus of the ocean waves, and the rustlings and calls of wildlife. In the sun’s first glow, the land stills my despair.

Arguably a profoundly ironic ending to a career of making art that sounds alerts to the destruction of the environment. But there will be no managed retreat. The reality of anthropogenic activities in the name of progress is that there is very little place left to retreat to from rising sea levels, floods, fires, desertification, habitat fragmentation that precipitates zoonosis, loss of clean water, loss of biodiversity, particularly of pollinators, atmospheric rivers, air pollution, even if policy makers convene conference after conference and study after study to discuss the “managed retreat” of living bodies from harm.

In my studio, I settle into my rocking chair and take time to study the opposite shore out my French doors, the clouds, the woods I see. I then make the first mark on paper or a small square linen canvas, distilling my perception of the invisible creep of sea level rise. I struggle with my palette to capture the eternally mobile light at this shifting edge between land and sea. Sometimes a smaller work will be realized large enough for me to feel like I can stand in the waves.

Studio interior upon entering the Old Sawmill, 2022

Studio interior upon entering the Old Sawmill, 2022

About the Author

“Eco-artivist” Aviva Rahmani has won numerous grants and fellowships and is written about and exhibited internationally, including the Cincinnati Center for Contemporary Art, The Hudson River Museum, The Center for Maine contemporary Art, Sichuan Fine Art Institute, Yuan Museum, Chongqing, China, KRICT Gallery, Daejeon, South Korea, the Independent Museum of Contemporary Art, Cyprus and in collaboration with the National Centres of Contemporary Art (NCCA), Ekaterinburg & Moscow, Russian Federation the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art and the Cultura21 Group at the Joseph Beuys 100 days of Conference Pavilion, Venice Biennale. She is an affiliate of the Institute for Arctic and Alpine Research at the University of Colorado at Boulder, gained her PhD in environmental sciences, technology and studio art from the University of Plymouth, UK, and received her BFA/MFA from CalArts. Rahmani authored Divining Chaos: The Autobiography of an Idea and co-edited Ecoart in Action: Activities, Case Studies, and Provocations for Classrooms and Communities in 2022. She is the co-founder of the ecoart listserv. Her current project “Blued Trees Opera” challenges ecocide. Rahmani divides her time between Vinalhaven Island, Maine and the city of her birth, New York City.

Acknowledgement: The author wants to especially thank Gillian Goslinga for her meticulous and insightful editorial support.

Return to top