In the years that farmers cleared their fields

by throwing flames across the nights,

half-mile rows of black black smoke

leached across late autumn days

until the west wind came with the frost

and blew the burned soil away—

that great prairie wind, pushing leaves

and garbage and ash from the river edge of Adams

County to well past Terre Haute—that wind,

that just one time before, my father said,

had yielded magic.

Come outside now, he, rousing me, said, the wind

all last week has moved the Mississippi

flyway to the east.

And pointing, showed, how the old pine just out the door

shimmered, shimmered—the slow beat of

a million wings all aglow such brilliant orange

that the morning star could blush that morning only pink, watching

as his familiar lips touched my ear, his family

code – this secret is ours, only ours—

and he whispered then only one word: Monarchs.

Then warmed awake those wings spread wide,

each a book of prayers I felt I once

could read, such delight, such despair,

I dared not even breathe

so breathless watched them rise

from our tree, creatures made of air,

so light their launching stirred not

a single needle. And so my father’s lips

and my ear became blessed, and all our years

of secreting were made holy, holy,

holy ever after by the touch of the great kings

who once had rested here.

NOTES

Growing up as the third generation in a tiny, tiny town in rural Illinois, it is nearly impossible for me to separate the land itself, my father’s body’s memory of that land, and my own body’s memories. I roamed the same woods, climbed the same trees, slept in his room at my Grandma’s, and experienced all of those through his stories and memories as much as through my own body and senses. To have grown up embedded in a place is to have permeable skin – what was inside me and what outside of me were so interconnected that I remember my childhood body as geography – that day biking home between the high corn when the humidity left me just as wet as the swim in the lake, that day shrieking in joy in the cold on the sled down the hill, that day running in pure terror through hickory woods chased by a wild hog and how the green was both smell and taste. To live in exile from that land—the cost of breaking family secrets – is to live unsure, still after all these years, of the actual boundaries of my body. I left because I wanted to live whole, not knowing I was trading having a whole spirit (and future) for having a whole body-world. I’m glad I made that trade, yet much of my writing is really just counting its cost.

About the Author

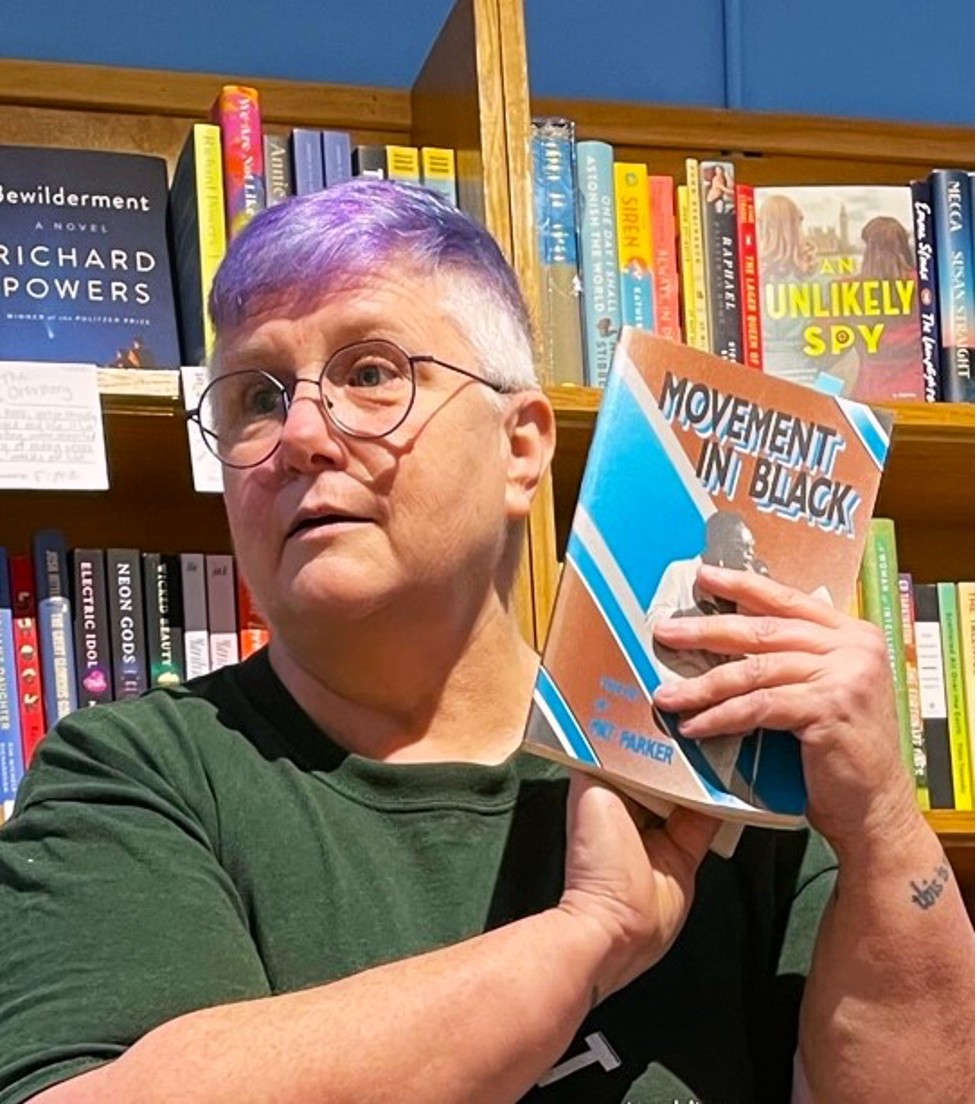

Elliott batTzedek lives in Philadelphia, and is a Jewish dyke of mixed-race and Midwestern descent, She holds an MFA in Poetry and Poetry in Translation from Drew University, where she received the Robert Bly translation prize, judged by Martha Collins. She works in four slightly different parts of the bookselling industry, and also as a liturgist for Jewish communities across the U.S. Her work appears in: American Poetry Review, Lilith, Massachusetts Review, Sakura Review, Cahoodaloodaling, Naugatuck River Review, Trivia, and Poemeleon. Her chapbook the enkindled coal of my tongue was published in January, 2017 by Wicked Banshee Press.

Return to top