Quitting Chemo

December 31, 2016:

On a big city street, I come face to face with an old man, soft white hair on both sides of his face, soft round cheeks, incredibly sweet smile and attitude. He looks me in the eye with such tenderness and benevolence as I’ve never experienced before. We are actually lying face to face on our bellies on a sidewalk.

On a big city street, I come face to face with an old man, soft white hair on both sides of his face, soft round cheeks, incredibly sweet smile and attitude. He looks me in the eye with such tenderness and benevolence as I’ve never experienced before. We are actually lying face to face on our bellies on a sidewalk.

He asks: “What’s going on with you? What’s at stake?” Waving one hand over me with a friendly smile, as if he wanted to indicate: this (chickenpox) is not such a big deal after all.”

He asks: “What’s going on with you? What’s at stake?” Waving one hand over me with a friendly smile, as if he wanted to indicate: this (chickenpox) is not such a big deal after all.”

“I don’t know,” I say,” I don’t know yet.”/

“I don’t know,” I say,” I don’t know yet.”/

He is nodding, seriously: “I see,” and wants to get up.

He is nodding, seriously: “I see,” and wants to get up.

“Yes, I know!” I exclaim with the next breath: “I don’t want my body to be intoxicated any longer. I want to stop chemo.”

“Yes, I know!” I exclaim with the next breath: “I don’t want my body to be intoxicated any longer. I want to stop chemo.”

“Oh?” He says, surprised and getting more serious. “I see.”

“Oh?” He says, surprised and getting more serious. “I see.”

I feel that my answer is taking us to a different level and would like to go on talking but he is already walking away, talking into a cell phone on his left ear. I know he is delivering my decision to higher spiritual guides.

I feel that my answer is taking us to a different level and would like to go on talking but he is already walking away, talking into a cell phone on his left ear. I know he is delivering my decision to higher spiritual guides.

In January 2017, I tell my oncologist that I wish to quit chemotherapy. I am relying on the messenger of my dream, feeling backed up by it. However, once inside the hospital, in a small examination room, I feel the pull of the institution. The oncologist is not pleased with my announcement. According to her, the cancer might take over rapidly in my body, especially in the liver.

“I would consider radiation, should there be more brain tumors,” I tell her as she washes her hands and dries them with a paper towel. “And I would continue to do the CAT scans and the brain MRI’s.”

“Why would you want to do the scans if you don’t continue with the treatments?” she retorts, turning her whole body abruptly to face me. I am struck dumb. Does she mean to refuse doing follow-ups if I don’t continue chemotherapy?

“Would you reconsider your decision until we meet for the results of the last scans?” she asks. I nod. I’ll think about it. That’s as much as I can manage to end this conversation without overreacting.

Oncologists brandish the threat of death without chemotherapy here. Having lived fifty years in Switzerland and Germany before coming to Montreal I was used to complementary medicine, a combination of allopathic, naturopathic and homeopathic approaches. In Montreal I have had to face a rather dismissive attitude toward complementary medicine.

The doctor and I meet again a week later both knowing a decision will be taken. My friend Ginette is with me. The oncologist enters the room with her usual friendly smile, stops in front of Ginette, introduces herself and offers a hand shake. I hold my breath. It took her several years before she greeted Lise, the woman at my side who takes notes and asks questions. I can’t remember a handshake between them. A murky sensation is creeping up my spine. I can feel the pull: Look, how friendly we are! Be-a-good-girl, do-as-we-say.

The oncologist repeats her concern about possible liver deterioration within the next three months. If that should occur, the liver won’t be able to deal with another chemotherapy, and she won’t be able to do anything more for me. She wants me to understand the facts fully. I reassure her that I take full responsibility for my decision. That I’d like to take that weight off her shoulders. “You can’t,” she says. “The weight is there, but that’s ok.”

For many people cancer has turned into a chronic disease and can be treated with long-term chemotherapy. I have benefitted from it myself. But with the dream message a shift has taken place. A veil is lifting. It is a daring decision I am taking. A deep breath moves through me pushing me to stand on my hind legs. Sniffing a fresh breeze. The salty taste of freedom, of setting off towards a new shore- or towards the other shore.

I wish to take my life back into my own hands, my whole life. I am taking back the part that had started to rely on the treatments. They may prolong your life all right but you hand over a big part of your innate vitality. You forget what you know. You let the drug handle it. The drug is a dimmer. It attenuates your life force, your knowledge. It suffocates your own voice. Fills your mind with fog and fatigue (e.g. maybe slack off in your daily Qi Gong practice to renew life force and build up energy).

Walking away I can feel the hospital at my back and everything I no longer have to do. When you enter the cancer clinic a huge machine grabs you. You have to follow the machine’s programmed orders step by step. Between individual steps you still meet a real human being from time to time. You still have a sheet of paper in your hands that you hand over to the receptionist for the blood test. The receptionists at all the desks are now typically staring at a computer screen with furrowed brows, tense backs, tense shoulders.

After the blood test you have to wave your health insurance card in front of a check-in screen. You have to hold it at the right angle so that a red vertical line on the screen hits its bar code. Your first name and the first three letters of your last one appear on the screen. One of the many dissociating moments of the day. “Hi Verena,” you say to the screen. Everybody fiddles with their card to hit the right angle for the machine. Volunteers are ready to help. Like with bank machines, in super markets and airports you have to learn to check yourself in and then “be in the system.” After that, you head over to reception and hand over the hospital card to a live secretary to be registered for a doctor’s appointment or a treatment. Then you take a seat and wait amidst the piercing Ding-Dong from loudspeakers and human voices calling patients into doctors’ offices. In terms of noise level it is not that different from a bus terminal. The waiting hall is full. Each and every person waiting there has cancer. Treatment rooms are full, the machines are running, the drips are dripping drip-drip-drip.

There is a poster in some examination rooms that announces: Your chemo day. It shows picture by picture how chemotherapy is applied to a smiling female patient by a smiling female nurse. They suggest a friendly procedure and an easy-going treatment. The pictures don’t inform you about dizziness, nausea and fatigue, to name some of the milder side effects. Nor the constant lack of energy that sometimes morphs into listlessness. There is no such thing as your chemo day. The possessive pronoun doesn’t apply. A chemo day is not an achievement or a cherished belonging. It is neither inspiring nor nourishing.

The nurses are busy administering different drugs for different patients, putting on and taking off light blue disposable coats, blue rubber gloves, a mouth protection or even a transparent visor that makes them look like a blend of a police officer and a medieval knight. They put on the visor to protect their face in case a plastic bag breaks and toxic medication splashes at them. “It happens rarely,” one of the nurses explains, “the technology has been improved. But nonetheless we are exposed to the chemicals eight hours a day.” They have to check the computerized machine that times the different drips. From time to time the machines are replaced by new models. Pharmaceutical computer technicians, a female technician in high heels and a tight black evening dress and a male one in a banker’s outfit give instructions and supervise the correct procedure. The nurses have to learn the programming of the intricate machine. They are responsible for setting the exact timing and dosage for the medication. For weeks, their gaze stays fixed on the slim screens when they approach my seat. To serve the machine properly is paramount. Once the procedure has turned into routine, their extreme stress level lowers. They are again able to switch their gaze between machine and patient.

The small plastic bags with the toxic drug and the saline solution dangle from the IV stand. Just looking at them makes me nauseous. The fact that I’ll deliver part of the toxins that drip into my blood stream with my urine into the water table and will add to the pollution of the planet is utterly depressing. In bad moments, it makes me feel like a collaborator with Big Pharma. Consider non-recyclable waste alone: plastic bags, tubes, syringes, gloves, coats and visors. From there it is only one step to despair about the situation of the planet, its cynical destruction by corporate companies. Chemo waste is burnt at a very high temperature, I hear. Where? How? How are the emissions dealt with? Is the heat generated used for a good purpose?

I haven’t learned how the toxic liquid of chemotherapy running through my veins actually works on my cells, except that it is meant to kill any fast-growing cancer cells in my organs or tissues. The information I get, first from the hospital pharmacist, then from the internet, speaks of possible side effects only. It feels like murky offshore business.

What about the depths and hollows and cavities of my body, the veins sunken or vanished, the mucus membrane, the intestinal lining, my muscle tone? The streaked and brittle nails, the constantly broken skin on my fingertips– all that I can see with my eye. It is the invisible damage that worries me more. For each side effect there is a pill, which might have another side effect for which there is another pill to pop into a patient’s mouth. “I feel nauseous when I approach the hospital,” I once told the oncologist. She nodded smiling: “We have a pill for that!”

On a chemo day, a chemo burn may occur. I feel a strong sensation of burning as soon as the new drip with Navelbine starts. The nurse immediately increases the flow of the saline solution. Later the area around the IV needle starts hurting and gets numb; the nurse wraps my forearm in a warm, moist towel. Navelbine takes only ten minutes to run; the flushing with saline solution will require another twenty to thirty minutes. The last minute of vein-flushing I sense a huge pressure and congestion all around my chest as well as muscular pain. There is congestion in the head, too, and a chill again.

Without the monthly trips to the hospital a spell is lifting. In the space of freed energy, the connections to my body’s memories grow stronger. As I did as a small child I am pulling my hand away from an unwanted grip and guidance. I am repeating one of my earliest gestures, an early manifestation of my desire for autonomy and freedom: I want to walk by myself.

I can still feel the pull of the institution at my back. I am overwhelmed by my decision, and shaky. Can I do without their suggestions, their promised safety nets? What will become of me?

With time, out of the growing distance of time and space, something new is being born. It is tender like gossamer wings. Hopefully it will become as strong as a spider’s web. For the time being I feel its fragility.

I’ll never again have to lie in a comfortable reclining chair looking up at the plastic bags dangling from the drip stand to my right and wait until the toxic substance has entered my body, drop by drop, through the tube plugged into the port in my chest. Never again will I have to feel the venom seep into my blood and into layers of body tissue.( I often wondered why the nurse would squeeze the bag repeatedly at the end of a 30-minute treatment with Herceptin, pressing out every single drop. “One of these bags is worth 2000$,” she informed me. A sick feeling. How much profit is the pharmaceutical industry making) Life inside the body turned into wasteland, greyish and chemically alien. A pasty, lifeless skin and the smell of burned rubber. I want my life back in full colour and with all my cells sparkling.

No more chemo-related questions to answer: Tingling, numbness in fingertips and toes? Mouth sores? Any rash? Hives? Dizziness? Shortness of breath?

“It feels like small cushions under my toes,” I say. The nurse is nodding and ticking it off on her form. “Do you still feel the floor under your feet?” she asks. That would be the next stage, I assume. She doesn’t ask how do I feel with those padded toes, whether they make me feel insecure or anxious? It is a given that they do. Each question is a statement of what has happened or might change in my body. The body is rearranged and composed anew: This is how your future body will look and feel, disturbed and distorted by chemotherapy. The patient is supposed to familiarize her or himself with the drawbacks or losses, all for the greater good, the destruction of cancer cells. Like the proverbial frog put to boil in a pot with cold water getting gradually used to the heat until it is too late to jump out. With or despite chemo thirty percent of the cancer cells will stay in a patient’s body anyway. Who or what is taking care of the remaining thirty percent? My immune system, the very immune system that is damaged by chemotherapy. On and on the vicious circle churns in my mind.

With friends we share stories of fever, cuts, infections, accidents, fractures. Even vomiting or diarrhea are the stuff of dramatic and comic accounts. Trouble the teeth can give us offers great storytelling; everybody can chime in. The routine of treatment after chemo treatment is difficult to communicate. It is a downer. It is not a riveting story to share with friends. No sharing, more isolation.

Or could it be the myth of the descent to the underworld and finding the way back up? But this is not a heroine’s inner journey or a vision quest. It is a chemically imposed descent into a wasteland. Chemotherapy lacks the human dimension of myth. There is no space for the soul in the experience. The foggy mind and draining fatigue make it difficult to connect with the creative and spiritual realm.

There are no nature-related metaphors in chemotherapy

The pattern of illness and healing is reversed. The body’s self-healing capacity and self-regulation are silenced. White blood cells that normally deal with a cold or an infection are hit by chemo toxins, too. The white blood cell count drops. The body becomes more vulnerable if not defenseless. ***

I am still walking but don’t know whether I want to continue being alive or not. What exactly is my life? What does strength mean? And what am I meant to do here for the time being? Love for my life companion of twenty years is growing daily. Gratitude for the good life we share is paired with the distress of leaving her behind. The love relationship will come to an end because my life will come to an end in the foreseeable future. When I move closer to that thought my heart clenches. I turn my head abruptly around as if I could look away from it. We don’t talk of this often. What else can be said than: I don’t want to lose you, I don’t want to leave you?

It has become difficult again to believe that I could bring cancer, or rather the many cancers in my body, to a halt. There are moments and hours and whole days where I can’t feel the connection to a self that would orchestrate self-healing. Cancer is a big story, located in a barely deciphered territory. It seems too big for a singular I. With cancer, I am thrown into a void.

Breast cancer can lead to lung, bones, liver or brain metastases. The mapped territory is laid out on the other side of the table where the oncologist sits or the radio-oncologist or whomever you will meet along the road. Maps or a map do exist in their mind. You don’t know of a map. Cancer exposes the patient to an unmapped territory.

You stumble along. ***

There are healings.

In body awareness practices, I explore listening to the body and seeing it in my mind’s eye. I compare temperature and weight of both sides of the body, and colours. I scan volumes and spaciousness of organs, bones, limbs, and follow the breath everywhere from the many spaces in the head along the rib cage, the lungs, the sternum and the whole spine, the pelvis and down to every single toe. Doing so I am breathing life into my body, I am connecting with it. I am having a conversation much like a conversation with flowers and trees. Like on an outdoor walk, I am going for a walk inside the body, moving from place to place and over time getting to know them better and more deeply.

Life wants to be attended to with never ending presence like the incessant current that streams through a snake’s body. Life requires being present with every beat of my heart, fully.

Healing doesn’t primarily mean to get rid of something. Sometimes it means sorting out and mending. Sometimes it means transition and evolution, in short, the potential any crisis may offer.

Cancer cells are darker than healthy cells and need to be suffused with light. Mistletoe injections insert light into body cells. Visualising light I can move it through my body. Cells light up through creative activity, colour, drawing, moving and music.…

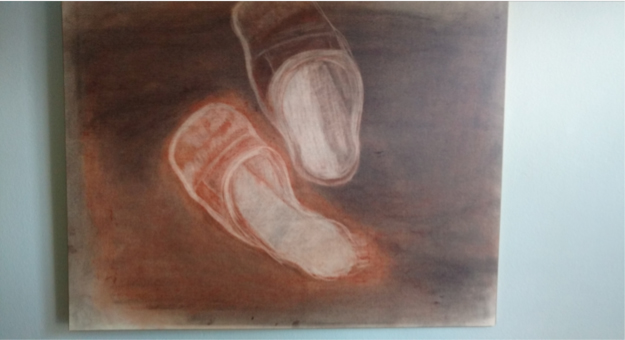

“The Slippers: A self-Portrait.” Exercise in charcoal and contè

A friend suggests organising three to four long-distance treatments per week by different people from our healing group. During a treatment my body temperature typically builds up from my navel where it is said that there is an ocean of Qi.

Original Artwork by Verena Stefan

The heat continues to increase steadily and spread through my whole torso. Both arms and hands tingle symmetrically. The tension in the neck, the fog and pressure in the head lift and vanish and with it the pollution from the hospital, the machines and the city noise, too. After forty minutes I feel completely restored. This is how it would feel to be connected to universal healing energy. It becomes almost palpable. Practising Qi Gong on a regular basis I might become capable myself of producing the same heat.

Sometimes the healing energy stays with me the whole day. The greyness and the numbing chemical substance start to lift. There is colour, and once a while, an image. I clearly saw my bare left foot, its toes covered with rich dark fresh garden soil dangling from my bed. My faculty of visualisation re-emerges after having been muted.

To life I cling passionately and stubbornly, to each leaf on the maple tree across the street, to the skies that open blue and hazy and thundering and filled with sheer light. To beauty I cling wherever I go and still, my body continues to tell me a story of its own and I don’t know the alphabet. I don’t know a first line to start with.

During a shiatsu treatment I saw a huge tree, one of those giant trees that stand their ground bow-legged so that a car could pass through underneath. Such is the level of comparison in our world: the size of cars. The image of the giant tree unfolded in the middle of my chest, where, a year ago, the surgeon had filled medicinal cement in the caved-in vertebra. In the middle of the tree trunk a concavity opened and in it sat a dark wooden goddess. The wood had blackened with age or with fire. She reminded me of Kali or of a Black Madonna.

When I told the therapist afterwards, he said no wonder you were growling like a grizzly bear when I worked that area. Release ferocity. Release radical healing power… ***

“Do you have to be productive rather than just be?” was one of the questions the psychologist asked me when I talked again about my fear of becoming marginal and useless. I have been living with cancer for more than twelve years. During that time, I wrote and published three books in Switzerland and Germany. I paid my taxes in Quebec, little as they were, in some years none. I benefit from a health care system that granted me all the necessary tests, surgeries and treatments for little to no financial contribution on my part. I definitely want to be productive or at least useful. Fact is, I am moving further and further away from it.

“Do you rest enough?” is the question every homeopath, astrologer, naturopath, massage therapist and acupuncturist has asked me throughout my life. Tilting their head and casting a scrutinizing look at me.

For the longest time I did not understand their question.

Sure I did rest enough. Weekends I slept in. I napped after love making.

Sometimes I even held a siesta on a Sunday afternoon. Year after year I took long holidays. I went travelling, once or twice for months. I kept a dream journal, I spent hours hovering over tarot cards. For many years I did yoga and belly dance.

Why then, after the first shock and tears, was my emotional reaction to the cancer diagnosis in 2002 a deep relief and the sigh: I don’t have to do anything anymore.

Not to meet expectations anymore. No need to present anything, to perform something because performance has become a new currency, a tyrant. Not earn my life any longer teaching creative writing and not getting enough students. Not to have to prove to a jury that I am worth the grant for a next book. Not to prove anything at all anymore. Not to wriggle along in a parallel life to institutions that demand degrees and CVs. Not to be part of a system that wants you to compete, to be better, stronger, more important than somebody else.

My deep relief after the first cancer diagnosis was buried again by me picking up my busy life of being somebody in the world. Four years later, with the first recurrence, I experienced the exact same emotion. Much like before a flight, a birth, a death, everything was suspended. Nothing else to do. Arrê t sur image. Again, I “forgot,” again being haunted by: I haven’t done enough, written enough. Only in 2012 on, with the first bone metastasis, did a shift begin to take place.

The Coarse Voice

Somebody is dying. The person who can’t go on as usual. The person who was coping all the time for years, decades. Coping puts stress on every single cell in the body: I am able, I am fit, I’ll rise to any given occasion: as a feminist, a lesbian, a writer, an immigrant and now as a person with cancer: I’ll overcome the odds, I’ll adapt to what is not familiar.

Lively conversations with more than one person have become too demanding. I look around the table where friends eat and drink and talk and laugh and move their arms and heads in whichever ways. I am acutely aware of how much is going on from my neck up being attentive and engaging in a conversation. Paying attention alone and keeping the neck for a while in the same listening position creates a strain. How rapidly eyes and ears switch between faces! I never noticed before how each of these minute movements strain my neck muscles. Everything happens too quickly, friends talk too rapidly, too nervously; voices and ideas and associations whirl in whichever direction and I get dizzy.

I take liberties. I get up from the table and stretch out on the sofa. In deep relief, I hear the low rumbling of a voice on the horizon that wants to be heard. It is approaching from the near future. Although still faint I can tell it is coarse, rough-hewn, without a refined syntax. Like a child that grew up in the woods and all of a sudden encounters civilisation. The voice is raw, knowing, radical.

In 2015 I temporarily lost my voice, and the Coarse Voice made its entrance. The ORL specialist confirmed the family doc’s assumption. A metastasis had touched the recurring nerve to the larynx and paralysed the left vocal cord.

The coarse voice enters this text bellowing. It is blunt, croaking, hot and blurting. It does not always follow grammar and the known order of syntax. It makes its entrance with eruptions. The coarse voice tells me what to do.

Me taking me in my arms. My voice and my spine need me connect with them, and stay connected.

“What would you do if spine was a sick person?” it asks, growling.

“I’d hug it and touch it;” I say, “and give it a massage.”

“Yes,” says coarse voice, “you do that and you tell your spine that you love spine and you stop treating ailments the way childhood illnesses were approached: What is it again? What does she have now? Then some care taking and get rid of it. You stop doing that now; you switch to love and love your bones and strange voice and touch them.” Hot gets in every cell, whole body gets hot and big, heat evaporating from soles of my feet.

“I love you deeply,” I say to me, “you just wonderful, your life meanwhile vulnerable like nature, attacked by cancer and polluted by chemical treatments. We fight to protect environment, but why say environment? Wrong thinking to think we in the middle and something around us. That something is nature. Why not say protect nature, she in big danger, somebody been stabbing her for so long, she already in emergency room and still somebody stabbing her. She our mother, she center stage. She life. “I am my care taker now,” I say to life, “I can tell what you need.”

….What is body? We together in a different manner now. What does liver need? I ask. Spine, neck, T12, coccyx, brain, throat with scarring tissue after radiation? What story does my right arm tell me? Numbing like a blood pressure cuff. Does it say: nerve from C7 leading down to small finger or does it say: brain tumor?

Body is a big reliable ally. Says: Take rest. Repose. Take more rest. Enjoy rest. Rest a lot. Enjoy being, carefree being. You don’t need to worry about money anymore. Not worry about achievements either. You done a lot. You do have time and you can do what you like as you like.

By Garden I Mean…**

Summer, 2016

By garden I mean energy. By energy I mean benefitting from the earth in my muted fatigued post-radiation and dizzy steroid-state. Walking the land and sitting on the ground sends a current of energy through my body. Within hours I am again able to climb the narrow staircase in the house without effort…

By garden I mean the heat rising from the soil. I never know how this happens here, on this continent. Lakes may still be partially covered with ice or you might even walk on a frozen lake, and all of a sudden heat is evaporating from the earth. She is breathing in and breathing out in hot tidal waves…

By garden I mean indulging in summer’s light…

By light I mean we are falling upwards into the enormous skies swimming in the incessantly streaming light…

Summer Solstice, and a jubilant morning with 4°Celsius at six am. Summer fruit, a mouthful of berries; they crunch with the first bite, then juice and munching. Barely out of winter the high season of the year opens with light and dry heat…

Divine evening light, blue skies with rosy-fingered and dove-blue ribbons of clouds. The water lilies will soon open their yellow cups; the bull frogs have started their uproarious nocturnal mating…

By brief glimpses of beauty I mean moments in which I am fully present. Daily images and sensations I know from sixteen Quebec years return, les gestes et sensations that belong to Quebec summers. Breathing in the fragrance of pine trees and their resin’s drip I shuffle along with naked feet striking dry needles and tiny cones. The soles of my feet meet different textures with each step. Each and every sensation seems stronger and more in focus. By focus I mean I am trading my dazed state for a more familiar quality of perception…

By garden I mean bliss. Every time I walk around the house I put my nose into the opening flowers of the jasmine, breathing in its beloved fragrance. Around the pond orange daylilies and the white chrysanthemum will start blooming anytime now. In front of the house it is the blue low tender campanula. The flaming red of bee balm, des monardes, will follow soon neighbouring the tall queens, hollyhocks, les roses trémières.

By garden I mean gentleness offered in fathomless sleep: My lover hears me announce loud and clearly at four in the morning: Life is good.

By garden I mean listening to Thich Nhat Hanh:

Walk as if you are kissing the Earth with your feet.

You carry Mother Earth within you. She is not outside of you.

Mother Earth is not just your environment.

Real communication with the Earth… is the highest form of prayer.

By garden I mean a language that exists in the now. Now is reality. Now and now and now. Green caterpillars on black currant leaves. The first shoots of peonies, of rhubarb. The first two tiny leaves of a calendula, a green bean.

* Editor’s note: Verena died November 30, 2017. In the last years of her life, she had been working—in English for the first time—on a book about living with cancer, a book she was not able to finish. I had been one of her readers in those years and before she died I got her permission to excerpt from the manuscript for this issue. “Quitting Chemo” has been culled, edited, and pieced together from the writing in that manuscript.

** “Just Being” is a short video Verena made about living with cancer, gardening, love, and thinking about death.

https://digitalstories.ca/video/just_being

About the Author

Verena Stefan was a renowned Swiss German writer. She left Switzerland in 1968 at the age of twenty-one to live in West Berlin and elsewhere in Germany for about thirty years before coming to Montreal in 1998, where she lived till her death in 2017. Her books include Häutungen (1975), (English translation Shedding, Daughters, Inc., 1978), and a new and expanded edition of Shedding and Literally Dreaming (The Feminist Press, New York, 1994). Among her recent publications are : Fremdschläfer, (Ammann, 2007), French translation: D’ailleurs, Les Éditions Héliotrope, Montréal, 2008); Italian translation: Ospiti Estranei, (Lucian Tufani Editirice, 2012) “Doe a Deer” in: Best European Fiction (Dalkey Archive Press, 2010, trans. Lise Weil) Als sei ich von einem andern Stern (As if I Were from a Different Planet. Jewish Life in Montreal). Co-ed. with Chaim Vogt-Moykopf. (Wunderhorn, 2011) Die Befragung der Zeit (Nagel & Kimche, 2014), French translation: Qui maîtrise les vents connaît son chemin (Héliotrope, 2017).

Photo by Myriam Fougeré

Return to top