June 2017, Issue #5

Making Kin: Part II

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Lise Weil

Editorial

Rachel Economy

A Home for the Seeds

Lou Robinson

Fettered

Wendy Maruyama

The WildLIFE Project

Deena Metzger

The Mystery: Approaching the Elephant People

Lois Red Elk

Porcupine on the Highway

Take Her Hands

Take Her Hands

Lora Matz

Love’s Awakening

Erika Wurth

Arcing towards the Sun

Cold and Tired Wind

Cold and Tired Wind

Anne Bergeron

Winter

Sheryl Noethe

Dimly Lit Ballrooms

BIO-EMPATHY

Writing to Re-See the World. A Discussion

Kyo Maclear

Diorama ThinkingCatherine Bush

Writing the WeatherSharon English

Making Room for WorldAlissa York

Bio-empathyDiane Raptosh

From The Zygote Epistles

Karen Malpede

There’s a Wilding Inside: Theater, Ritual and Biophilia

Petra Kuppers

Dolphin Pearls

Sue Cerulean

After•Word Eve Saulitis’ Becoming Earth: Essays

Jaime R. Wood

Yaquina at Low Tide

The Seedlings

The Seedlings

Felicity Died on a Cold Metal Table

Felicity Died on a Cold Metal Table

Lives of Elephants

Lives of Elephants

Sara Wright

Lily B., My Telepathic Bird

Carol Corwin

Holding the Sparrow

Lise Weil

After•Word Kathleen Deane Moore’s Great Tide Rising

AFTERMATH: 11/9

Praying Amid the Damage: Dreams, Nightmares, Visions

Lawrie Hartt

Roses for the Dead

Miriam Greenspan

Trump Nightmares and the Medicine of Resistance

Sharon English

Nourishing the Future

Kristin Flyntz

Truth and Silencing

Aviva Rahmani

Raped by Monsters; Crossing a Rickety Bridge

Shula Levine

Everything is Alive and Communicating

Laura D. Bellmay

Cobra Issues a Warning

Wendy Maruyama

The WildLIFE Project

I am a studio artist with a background in furniture-making practices: my primary medium is wood but I also use glass, steel and video components. My work has been motivated by experiences derived from history, ethnicity and/or identity: a body of work entitled Executive Order 9066 has taken on an element of activism, advocacy and education, requiring research in American History in tandem with my own family history. The experience of making this work was inspired by interpretive exhibitions associated with natural history museums and national park sites leading to my latest work.

The problem of the increasing loss of wildlife is of deep concern and a focal point in my artwork. My first piece on this theme was made in 2004, as an homage to the Tasmanian Tiger, a species made extinct by humans in Tasmania. http://wendymaruyama.com/artwork/173482-You-don-t-know-what-you-ve-got-til-its-gone.html. The wildLIFE Project is driven by my own personal passion for animals and addresses the plight of elephant and rhinoceros poaching and the terrible loss in these animal populations.

There is a historical and artistic connection between furniture and memorials, including coffins and sarcophagi. At some point in history, the designs of these two seemingly disparate classes of objects were intertwined. Several of my recent works are in the form of cenotaphs, sarcophagi and Buddhist shrines.

The wildLIFE Project began with the construction of five large life-sized elephant masks. The challenge for me was to resolve how I could make such large forms without the weight and mass that one would normally encounter. I work alone in my studio and I wanted to find a way to make these and still be completely independent. I used to sew clothing when I was a teenager and so I adapted a patternmaking technique that would allow me to work with thin lightweight pieces of wood and stitch them together in such a way that the form would become a three-dimensional form when hung on the wall. The process was also cathartic: the process of stitching these pieces became a therapeutic act of trying to fix a very complex problem (poaching).

Cenotaph. http://wendymaruyama.com/artwork/3844286-Cenotaph.html

At the turn of the 19th century, there were approximately one million rhinos. In 1970, there were around 70,000. Today, there are only around 28,000 rhinos surviving in the wild. Three of the five species of rhino are “Critically Endangered” as defined by the IUCN (World Conservation Union). The Southern subspecies of the white rhino is classified by the IUCN in the lesser category of being “Near Threatened”; and the Greater one-horned rhino is classified as “Vulnerable”; even this is considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the wild.

The prominent horn for which rhinos are so well known has been their downfall. Many animals have been killed for this hard, hair-like growth, which is revered for medicinal use in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore. The horn is also valued in North Africa and the Middle East as an ornamental dagger handle. The white rhino once roamed much of sub-Saharan Africa, but today is on the verge of extinction due to poaching fueled by these commercial uses. Only about 11,000 white rhinos survive in the wild, and many organizations are working to protect this much-loved animal.

Sarcophagus. The sarcophagus form was used to house 16 life-sized elephant tusk forms that were hand-blown out of glass by a team of professional glass blowers who assisted me during my residency at Pilchuck School of Glass. Symbolically, the use of this material was meant to evoke the beauty of the animal from which these tusks were taken from and to, despite the size of these large animals, reference the fragility of life.

***

The following interview with Maruyama appeared in Art Newspaper:

I have had a lifelong fascination with wild animals ever since I was a child. My first work related to wildlife was in homage to Ben, the last living Tasmanian Tiger — these animals were hunted with no justification whatsoever. By the time they put a ban on hunting these creatures, they were already on the brink of extinction and it was too late. http://wendymaruyama.com/artwork/173482-You-don-t-know-what-you-ve-got-til-its-gone.html

What is your relationship with the ivory trade/animal conservation?

Only that it became a personal cause —wild animals, without any action by humans are defenseless: at the current rate we will have lost 30% to 50% of species by mid-century. This is an alarming statistic considering the current crisis is being caused entirely by humans. Ninety-nine percent of currently threatened species are at risk from human activities, primarily those driving habitat loss, introduction of exotic species, and global warming.

How does this series mark a departure from your earlier work?

This work moved laterally from the realm of social justice to environmental causes. The previous work was intended to bring a very dark part of American History (the Japanese American Incarceration during WWII) to life — and it affected my own family very directly. It was also very relevant in terms of what was happening now, with all the post 9/11 anti-Muslim rhetoric, the anti-immigration laws, and this remains sadly relevant today. We have clearly not learned anything.

What new materials did you use?

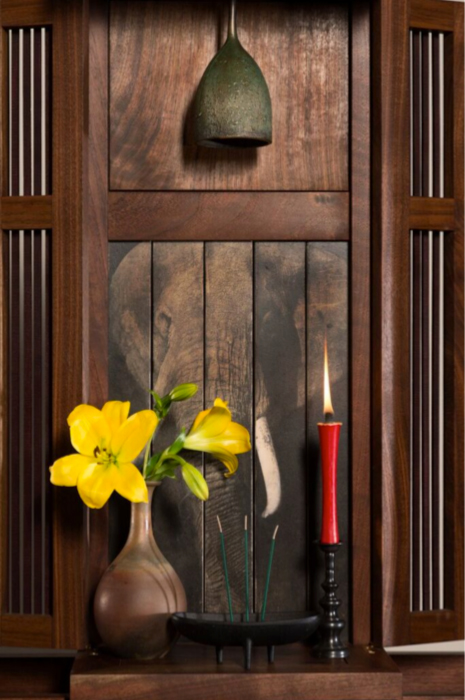

With wood being my primary material, and I have used glass in many forms over the years, as well as video components, I suppose the newest material is steel, which provided a counter against the layers of sheet glass in one piece (Cenotaph). Also, as a deaf person, I don’t often consider sound in my work, but the sound of a bronze bell ringing signifies the death of an elephant — it rings every 15 minutes, which is when an elephant is killed for its tusks. I might add, that the Bell Shrine was all made of wood that was salvaged from a defunct rifle factory — all the wood was shaped like rifle gunstock — and it felt great to cut those things apart and make the pieces work for my shrine.

How was the experience? How does that relate to the subject matter?

The materiality of the wood, the glass, the steel all have emotive qualities that lend themselves to the individual pieces. The process also plays a part — I remember just sobbing over the loss of one of the largest living “tuskers” — he was shot and killed for his massive tusks and I had designed the elephant masks to be made of smaller pieces of wood, and stitching them together — the process and method of fabricating this work became cathartic as I was stitching these parts together — hearing the bell ring in the background, and smelling the incense I would light in the Bell Shrine. Interestingly too, having previously become introduced to many friends who were Buddhists while working on the Executive Order 9066 work, I learned about the ritual of the Buddhist shrine and its meaning:

The most basic elements of the obutsudan are

- The Central Object of Reverence or Worship (Gohonzon). The elephant in this case.

- Flowers. Always on the left, representing impermanence.

- Candle. Always on the right, representing unchanging truth (Dharma). Yes, we see the candle as a symbol of transience as the burning flame consumes the candle. But the candle works as a symbol of unchanging truth because the flame persists, even if transferred to another candle.

- Incense Offering/Burner. In the middle, in front, as it relates to our spiritual state in the present moment, as a kind of living synthesis of transience and permanence. Sometimes our transient life is identified as horizontal time, and unchanging truth as vertical. Burning incense brings us to the current moment in which we experience the intersection of horizontal and vertical time.

What are you hoping visitors take away from the show?

That they understand what is happening, not only with elephants, but ALL of wildlife, and I hope they will consider becoming activists or advocates themselves, and spread the word that wildlife needs help!

Wendy Maruyama has been making innovative work for 40 years. While her early work combined ideologies of feminism and traditional craft objects, her newer work moves beyond the boundaries of traditional studio craft and into the realm of social practice. Born in La Junta, Colorado, to second-generation Japanese American parents, since 1994, she has been creating works inspired by the memory of her childhood growing up as a Japanese-American, her interpretation of her ethnic heritage, and her observations of the Japanese culture, looking in from the outside. Her latest work, The wildLIFE Project, focuses on the endangerment of elephants, a cause that is very personal to her. An educator for 35 years, Maruyama has recently retired from teaching at San Diego State University, and previously has taught at Appalachian Center for Crafts, California College of Arts. She has exhibited her work nationally, with solo shows in New York City, San Francisco, Scottsdale, Indianapolis, Savannah, and Easthampton. She has exhibited internationally in Tokyo, Seoul and London. Her work can also be found in both national and international permanent museum collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas; Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston, Australia; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Museum of Art and Design, New York; and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles.

Want to comment on any Issue of Dark Matter, fill out the form here.

Copyright © 2014-2021 Dark Matter: Women Witnessing - All rights reserved to individual authors and artists.

Email: Editor@DarkMatterWomenWitnessing.com

Please report any problems with this site to webmaven@DarkMatterWomenWitnessing.com